Source: Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems (JAMES)

An existing body of research indicates that climate change is making tropical cyclones wetter and more powerful.

Now, new research is indicating the same thing may be happening to the precursors of these storms: the wet weather systems that sometimes give rise to destructive hurricanes and often cause hazardous rain and flooding.

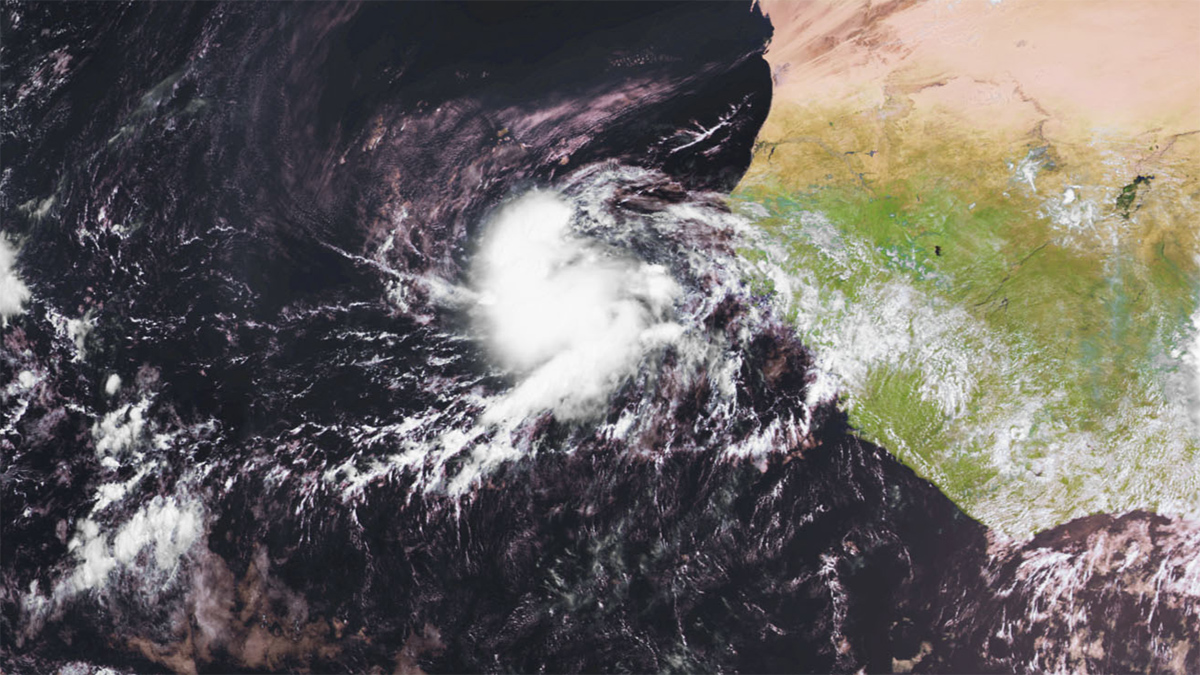

Tropical cyclones don’t spring into existence fully formed. Around 85% of Atlantic hurricanes, for instance, originate from African easterly waves, westward-moving disturbances of low pressure over Africa in which warm, humid air rises into the atmosphere from below and forms rain clouds. Despite these weather systems’ critical role as “seeds” for tropical cyclones, however, it’s not fully understood how climate change may affect their development.

Núñez Ocasio et al. recently investigated how African easterly waves might behave differently in the future because of climate change. To do this, Núñez Ocasio first developed a new regional weather model configuration that allowed for more realistic representation of possible rainfall extremes. Using this improved model, the team focused on the formation period of the wave that would become 2006’s Hurricane Helene and simulated how the storm might have played out differently in a warmer, more humid environment.

Under a scenario of high greenhouse gas emissions, the researchers found that by the end of the century, waves like the one that became Helene will grow significantly more intense, spinning faster and holding a greater amount of water vapor relative to their surroundings. At the same time, the waves will travel more slowly across Africa. Altogether, this means they will linger for longer periods while dumping heavier rain over affected areas, exacerbating the risk of extreme flooding.

Given that risk, the authors call for the use of high-resolution models like those in the present study to further research how African easterly waves will respond to climate change. Such studies may provide vulnerable communities with the information they need to prepare for extreme weather.

The authors also note that although forecasts with short lead times—the time between a weather forecast and the actual weather event—tend to offer higher accuracy, longer lead times may better account for the slower movement of future African easterly waves. (Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems (JAMES), https://doi.org/10.1029/2025MS005146, 2025)

—Sean Cummings, Science Writer