Uncertainty about running traditional field- or lab-based internships led to cancellations of many programs. At the same time, these circumstances have spurred innovative efforts to design alternative student programming.

Every year, undergraduate Earth system science students eagerly seek opportunities to gain research experience before applying to graduate school or entering the workforce. In the early months of 2020, leaders of geoscience research internships were busy reviewing applications, solidifying projects and logistics, and making offers to students for the summer of 2020, unaware of the looming impacts of the novel infectious coronavirus (COVID-19). The timing and persistence of the ongoing pandemic, however, threw these plans into a tailspin.

Uncertainty about the feasibility of running traditional field- or lab-based internships and other concerns led to cancellations of many programs, leaving thousands of undergraduates without jobs. At the same time, these circumstances have spurred innovative efforts to design alternative student programming.

Adapting Traditional Programs

Joining a scientific team on a ship, in the mountains, or in a lab can be an exciting way for undergraduates to become engaged in Earth system science and participate in research firsthand. For decades, undergraduate internships have brought together student cohorts for research experiences that are enriched with career development, cohort building, and training in technical and science communication. This valuable project experience and professional development have made these research internships highly valued by geoscience employers and graduate programs.

As news of closures marched across college campuses this spring, internship program leaders saw their hopes of running their programs fade before their eyes. All wrestled with the unknowns of campus dorm availability and converting an on-site program into a remote one on such short notice. The implications of hosting a student who might become ill with COVID-19 were also daunting. Many program leaders decided to cancel their programs, while others had that decision made for them by their institutions.

A few communities, including program leaders involved in the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates in the geosciences (GEO REUs) and members of the Council on Undergraduate Research community, came together to find alternatives, support each other, and share materials. Internship leaders at national laboratories like the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration acted quickly in deciding to postpone, cancel, or move programs online. And an intensive collaborative effort by more than 300 educators to create remote capstone field experiences for undergraduate geoscience majors was organized by the National Association of Geoscience Teachers and the International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

As the gravity of the pandemic became more apparent, GEO REU leaders organized twice-weekly “drop-in” video calls throughout April and May. There, individuals could share news about COVID-19 restrictions, their impacts, and ideas of how to adapt programs. Some participants reported that these discussions inspired them to modify their program rather than cancel it. The GEO REU community organized webinars, resources, and discussions for program leaders on mentoring students, moving internships online, antiharassment and antidiscrimination training, and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Programs have evolved differently, but a few models of adaptation have emerged in response to the constraints introduced by the pandemic.

Each program has evolved differently, but a few models of adaptation have emerged in response to the constraints introduced by the pandemic. They include the following:

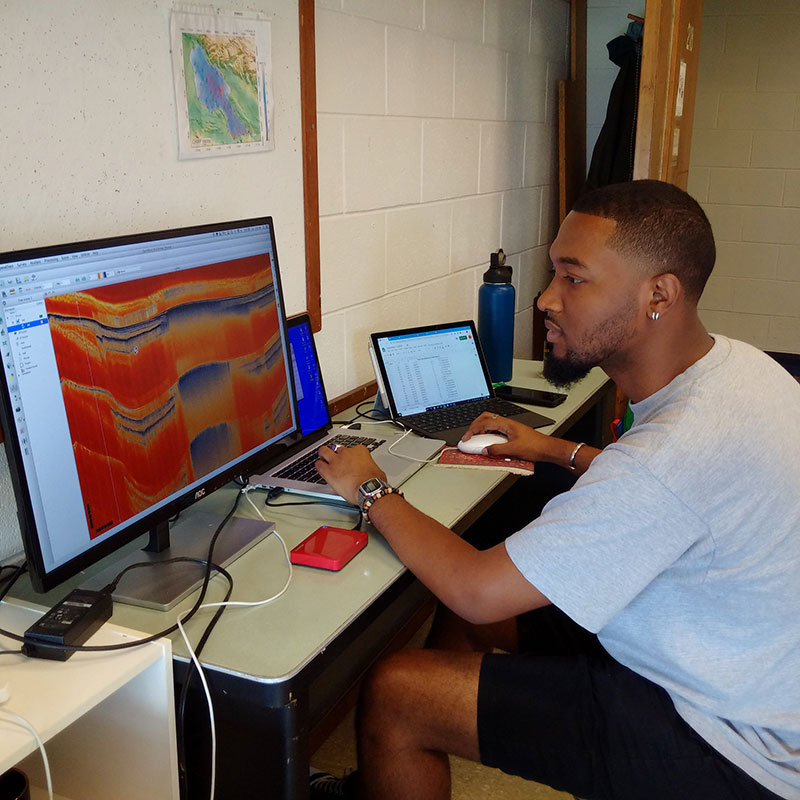

(1) In fully virtual internships, students engage in research with science mentors or teams and participate in career development workshops. Internships involving fieldwork or lab projects have been redesigned to be fully remote, for example, analyzing Colorado’s wildfire history in relation to climate change, studying severe weather events using satellite images, and sequencing genes in fish that tolerate high concentrations of toxins from fossil fuels. One student will analyze ground penetrating radar data collected by the research mentor this summer to characterize moisture in tree roots in Texas; others will use microscopes at home to measure samples of microfossils.

(2) In virtual professional development–focused programs lasting 1–2 weeks, students attend career and graduate student panels, prepare application materials for fellowships and jobs, and participate in communication and leadership training. Cohort building, which is important for students during internship programs and beyond, is facilitated through discussions in small groups in virtual “breakout rooms,” through icebreaker activities, and over social media. This approach has gained popularity among internship leaders concerned about not overburdening faculty mentors while still providing students with a valuable experience and income at a time when jobs are scarce. Some of these shortened programs will also provide brief, structured research experiences for the students.

(3) Virtual geoscience field camps and summer courses have been newly created for undergraduates. A few hundred faculty worked intensively this spring to develop remote experiences for students missing out on traditional summer field camps. Examples of these virtual field experiences include mapping geology in Yosemite National Park, in Ireland, and near the San Andreas fault in California using a wide range of digital tools and data. Some faculty are piloting free online courses that are garnering hundreds of participants, such as the full-summer seismology skill-building workshop hosted by the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology, which has an enrollment of 750 people.

(4) Pop-up remote research opportunities for students accepted into internship programs that were then canceled have been created. Scientists and educators have come together to host virtual research experiences, particularly for rising seniors for whom this is a last chance to participate. One example is the National Science Foundation’s Ocean Sciences REU 2020, which was pieced together quickly this spring in response to COVID-19 with the involvement of about 50 scientists across the country. In this effort, a student-mentor support team is hosting a weekly professional development workshop series, fostering cohort building, and providing additional mentoring, all virtually. Some potential student projects include investigating coral reef ecosystems using image-based data; studying how intense storms generate large, destructive waves; and developing educational modules on the impact of sea level rise on urban environments.

Challenges of Reprogramming

Converting a cohort-based, hands-on experience to a remote research endeavor with mentoring and professional development is daunting. There is uncertainty about dealing with time zones, how much time spent on video calls is fruitful, and how to develop a sense of cohort remotely. Mentors are trying to be cognizant of variability in students’ access to the Internet and compassionate about challenges in their home environments. In one program that could serve as a model, the internship director is matching student interns with graduate students who will offer regular near-peer mentoring.

For faculty, program leaders, and research mentors, this transition is occurring on top of shifts to online teaching, frequent COVID-19 contingency planning meetings, research and supervising responsibilities, and challenges in their personal lives. Many are piecing together time and working space in their homes while caring for children and dealing with isolation from family and friends, some of whom are sick, along with other responsibilities. The effort of so many in our community to come through for students by providing these many experiences has been impressive and inspiring.

At the same time, the economic impacts and disappointment that students experience with canceled or modified programs are profound. For those fortunate enough to be able to participate in remote programs, there is still sadness about missing out on the independence and excitement of discovering a new place, the informal learning and mentoring, and the long-term friendships that develop in person. Many will receive reduced stipends because of shortened programs.

Internship leaders and faculty have reported students being thrilled and grateful when an alternative to a cancellation is provided, even if it’s virtual. However, the recent events of racist violence and related protests and unrest have added yet more anxiety for students, program leaders, and research mentors alike. Acknowledging the emotional tolls of these events is proving to be an important piece of moving forward with these virtual programs and one that some students have said is helpful and appreciated.

Impacts on the Class of 2021 and on Admissions Processes

As geoscience research internships and field camps are adapted in response to COVID-19, expectations about students graduating with geoscience degrees must change. Missed or delayed research experiences and field camps will affect rising seniors disproportionately, as these students usually comprise the majority of participants. Many will not have the research and professional experience normally seen in applications to graduate school or geoscience jobs.

Graduate programs and prospective employers will need to adopt more holistic approaches for assessing applicants. Adjustments might include increasing their focus on technical skills developed in undergraduate courses, on professional skills honed in nonacademic jobs, and on duties and learning conducted in the home.

The extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic may have ripple effects on younger students coming through the educational system for years to come.

Graduate schools and employers will also need to consider potential socioeconomic barriers affecting students. Campus closures have negatively affected the most vulnerable students with the disappearance of on- and off-campus jobs and support such as in-person social support, mentoring, and mental health resources. And businesses affected by the recent unrest may lead to further unemployment. Many students have family members who have lost jobs and health insurance or who have become ill or passed away, thereby changing these students’ familial roles. Students without family financial support who are unable to earn money over the summer may not be able to return to college in the fall and therefore won’t be eligible to apply to graduate school. The permanent closure of academic programs—particularly in remote areas, such as Alaska—will further affect students.

The extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic may have ripple effects on younger students coming through the educational system for years to come. Across the United States, school will look different this fall, with staggered schedules in which different children attend school on alternating days, learning outdoors, and online classes. Universities and colleges will need to consider adaptations like bridging the divide between high school and college and changing their criteria for admitting undergraduate students.

Although much is lost by missing out on in-person, on-site teaching and learning experiences, converting summer programs to be remote is providing hundreds of undergraduates with opportunities. Faculty and students are expanding their skills in analyzing data with digital analytical tools and learning to communicate remotely more effectively. These changes may lead to different scientific collaborations and progress and, for students, to further development of their employable skills. After all, effective remote communication will be increasingly valuable as conferences, college courses, and scientific collaborations continue to shift online in the future.

The range of summer training options available to geoscience students is expanding and may come to attract a broader range of students than those who have participated in the past, including students who are tied to jobs at home, who are parents or have community responsibilities, or who have physical disabilities. It is our hope that the opportunities that we develop now in response to social distancing measures and the compassion that we develop in the time of COVID-19 may result in more equitable, accessible opportunities for students pursuing geoscience careers.

Author Information

Valerie Sloan ([email protected]) and Rebecca Haacker, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colo.; Rebecca Batchelor, Cooperative Institute for Research in the Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder; and Corey Garza, California State University Monterey Bay, Seaside

Citation:

Sloan, V.,Haacker, R.,Batchelor, R., and Garza, C. (2020), How COVID-19 is affecting undergraduate research experiences, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO145667. Published on 18 June 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.