The universe never fails to surprise. Take TOI-561 b, an Earth-sized exoplanet that circles its star on an orbit more than 30 times smaller than Mercury’s.

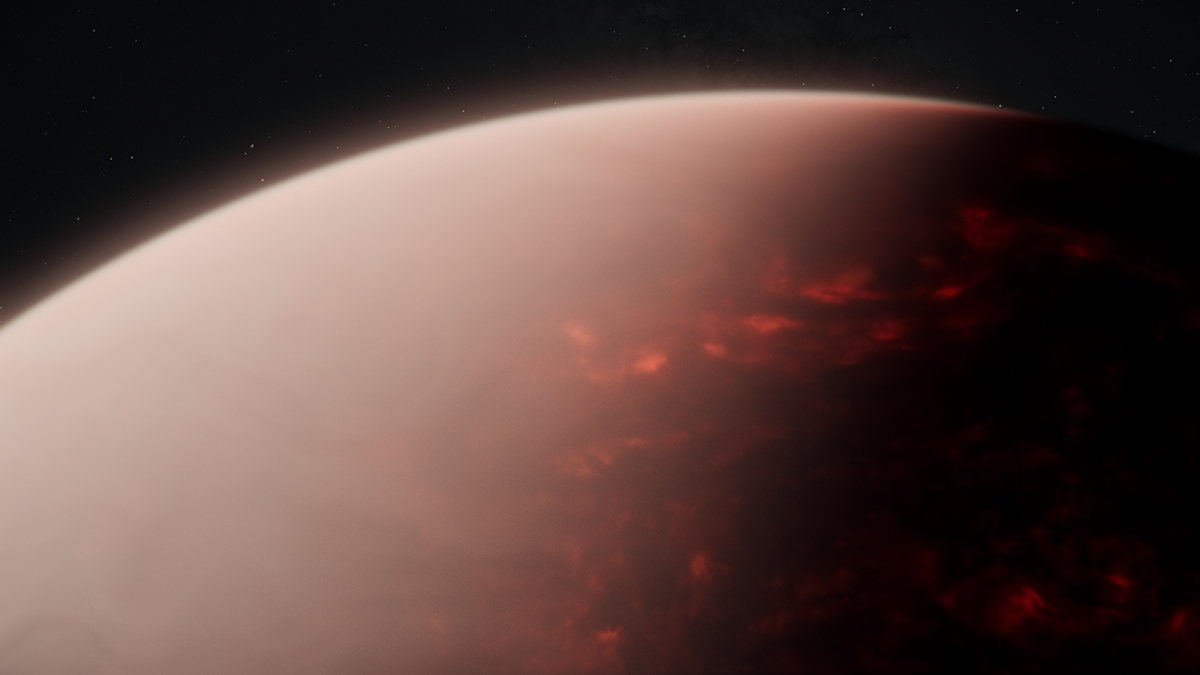

Despite being blasted by radiation to the point that its rocky surface is likely molten, TOI-561 b still seems to retain a thick atmosphere. This discovery, reported in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, shows that even highly irradiated planets—whose atmospheres should have been eroded long ago—can remain enshrouded in gas for billions of years.

Lava World

When it comes to constellations, Sextans (the Sextant) is largely unremarkable; its brightest stars can’t even be seen with the naked eye from a large city. But there’s a star in Sextans that is home to a miniature solar system: TOI-561, roughly twice as old as the Sun, has four planets orbiting it. And the innermost of those planets, known as TOI-561 b, holds the special honor of being what’s called an ultrashort-period exoplanet. That’s a world no larger than twice the radius of Earth that whips around its host star in 1 day or less.

“We do not expect that an atmosphere can survive.”

Ultrashort-period exoplanets are rare—only several dozen are known to exist—and they’re extreme: They orbit so close to their host stars that they typically have dayside temperatures above the melting point of rock, leading researchers to dub them “lava worlds.” Ultrashort-period exoplanets are also planets on a journey—it’s thought that they formed farther away from their stars and migrated inward over time.

Many ultrashort-period exoplanets observed to date also don’t have atmospheres. That makes sense, said Rafael Luque, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia in Granada, Spain, not involved in the new research. These extreme worlds are literally being irradiated by their host stars, he said. “We do not expect that an atmosphere can survive.”

A Puffed-Up World?

Earlier observations revealed both the size and mass of TOI-561 b. Taken together, those data suggest an anomalously low density for the planet, roughly 4.3 grams per cubic centimeter. (Earth’s average density, for comparison, is about 5.5 grams per cubic centimeter.)

There are several explanations for that finding, said Nicole Wallack, an astronomer at Carnegie Science in Washington, D.C., and a member of the research team. For instance, TOI-561 b might lack an iron core. But a more likely scenario is that it’s a puffed-up planet that appears larger and therefore less dense than it actually is, said Wallack.

And a thick atmosphere is the most logical culprit for a puffed-up exoplanet, she explained. “It could have an atmosphere that’s making the planet appear larger in radius but isn’t influencing its mass as much.”

To test that idea, Wallack and her colleagues, led by Johanna Teske, an astronomer at Carnegie Science, recently observed TOI-561 b and its host star using the James Webb Space Telescope. The researchers collected near-infrared observations of four orbits of the planet, each of which lasted only about 11 hours.

“Atmospheres are much better than solid rocks are at transporting heat.”

For this new study, the team focused on data collected around the time of so-called secondary eclipse. That’s when a planet passes behind its star, as seen from a telescope’s perspective. By comparing observations recorded when the star and planet are both visible to those recorded when just the star is visible, it’s possible to home in on just the signal from the planet, said Wallack. For TOI-561 b, the team divided that planet signal into seven near-infrared wavelength bins and looked at how the light was distributed as a function of wavelength.

That investigation allowed the team to estimate the approximate temperature of TOI-561 b: about 1,700–2,200 K. That’s significantly cooler than the roughly 3,000 K expected on the basis of the temperature of the star and TOI-561 b’s distance from it. “The planet appears to be colder than we would have expected,” said Wallack.

An atmosphere is the best explanation for that discrepancy, Teske and her colleagues proposed. The presence of an atmosphere would allow heat to be redistributed away from a planet’s warmer dayside and toward its cooler nightside. That process of heat distribution is much more efficient than relying on rocks to do the same thing, said Wallack. “Atmospheres are much better than solid rocks are at transporting heat.”

TOI-561 b might not be a complete outlier when it comes to having an atmosphere. After all, a handful of other ultrashort-period exoplanets, such as 55 Cancri e, are believed to be enshrouded in gas.

Hunting for Molecules

After analyzing the Webb observations, the researchers modeled signals that would be expected from an atmosphere containing varying proportions of molecules such as water, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide. They found that their data were no more consistent with one model than another. The relatively wide spectral binning that the team adopted—just seven data points over a range of roughly 2.7–5.1 micrometers—may have precluded detecting any molecule-specific features, the team concluded.

Even though the composition of TOI-561 b’s atmosphere remains inconclusive, there’s good evidence that it exists, said Michael Zhang, an astronomer at the University of Chicago not involved in the research. “I believe that there is an atmosphere.”

And that atmosphere is most likely composed of material outgassed from TOI-561 b’s molten surface. That inference can guide logical follow-on work modeling the planet’s atmosphere, said Zhang. “You can test compositions that you expect would be outgassed from the magma ocean.”

Analyzing TOI-561 b’s nightside signal—something that’s possible with the researchers’ current dataset—will also be important, said Zhang. It’s a tough measurement to make, but because atmospheres are good at redistributing heat, he explained, even the side of TOI-561 b facing away from its star should be detectable. “The nightside should be warm.”

—Katherine Kornei (@KatherineKornei), Science Writer