Higher temperatures continued to destabilize the Arctic this year. Effects ranging from permafrost thaw to volatile weather conditions are causing further damage to ecosystems and human communities.

Each year, scientists around the world, many of whom work and live in the Arctic, contribute to NOAA’s annual report of the region’s climate and environmental systems. The Arctic Report Card 2023 provides an updated look at a region facing increasing snow and ice melt, volatile weather patterns, and unsettled ecological communities.

“Everything just got a little bit more serious this year,” said Paul Overduin, a hydrochemist at the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research and the lead author of the report’s undersea permafrost chapter.

The report documents “a substantially changing Arctic,” said Walter Meier, a sea ice scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center and the lead author of the report’s sea ice chapter. Shifting conditions highlight the need for more data to better predict how changes in the Arctic will reverberate around the world, the authors said.

Arctic Vital Signs

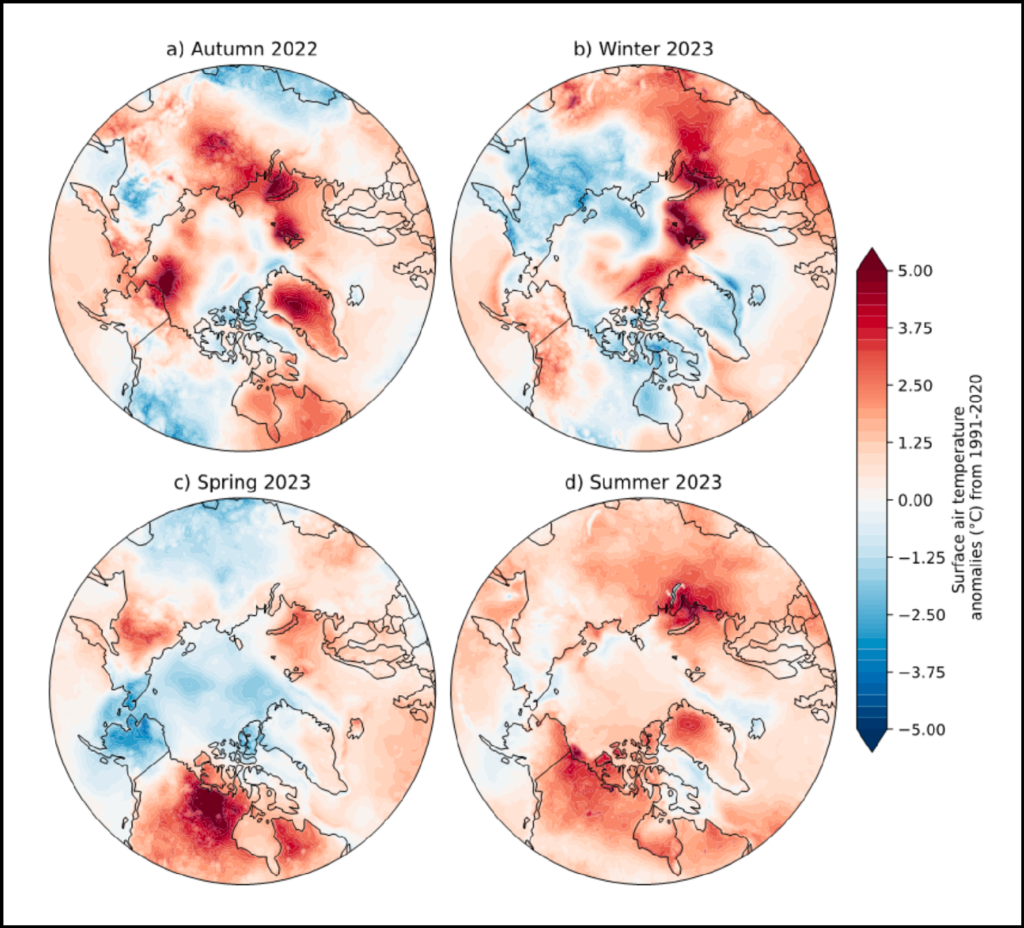

This year broke records once again in the Arctic: Summer temperatures were the warmest ever, snow cover in the North American Arctic hit an all-time low for May, and multiple locations saw record-breaking heavy precipitation. Surface air temperatures year-round in the Arctic were the sixth warmest since 1900.

Arctic sea ice cover this year continued its trend of below-average extent. The past 17 September sea ice extents were the lowest 17 on record. Low sea ice conditions and widespread thinner, younger sea ice seem to be a “new normal” in the Arctic, Meier said.

Sea ice reduces heat transfer between the atmosphere and the ocean, so less of it can lead to further ocean warming and additional ice loss.

More open water is also allowing for a rougher sea, Meier said. “There’s more room for waves to build up, meaning communities are getting flooded and there’s coastal erosion going on,” he said. And beyond the ice-free period, changes in the ice mean Arctic communities have to be careful when traveling. “The character of the ice is different and less safe, more prone to breaking up,” he said.

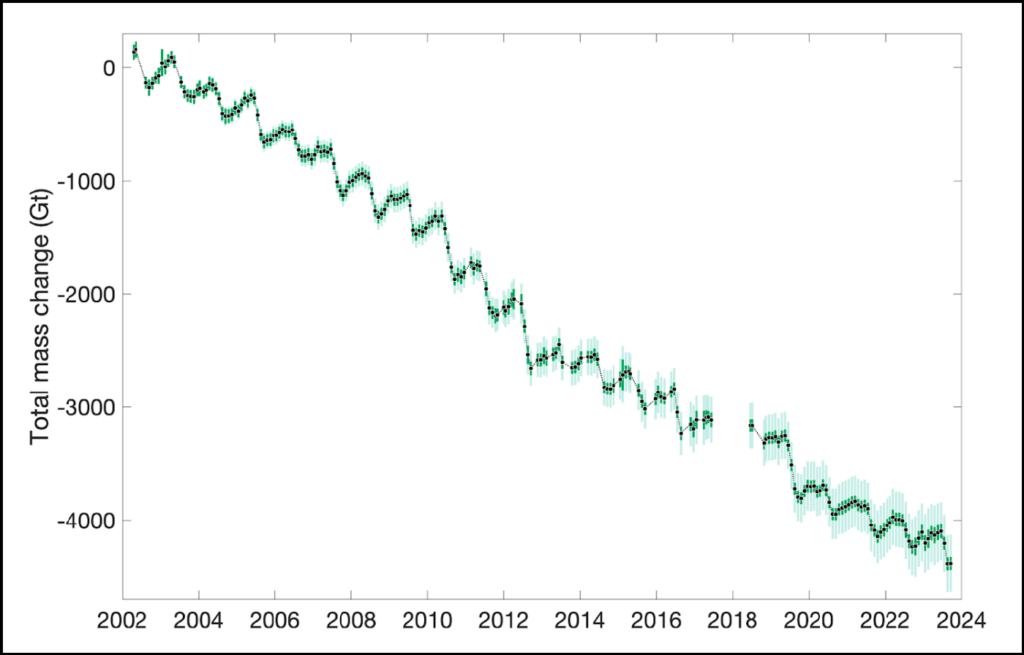

The Greenland Ice Sheet—the second largest ice sheet on Earth—continued to lose mass this year, too. Greenland’s Summit Station, the highest-altitude research station in the Arctic, reached temperatures above freezing and experienced melt for just the fifth time in its 34-year history of observation.

Warming air temperatures have contributed to an overall increase in precipitation in the Arctic. In 2023, the Arctic received its sixth highest precipitation levels on record.

In the warmest parts of the Arctic, snowfall is turning to rain. When that rain falls on snow, it freezes. “It can leave a very thick, icy crust on the surface that interferes with the grazing of ungulates like reindeer, caribou, or musk oxen,” said geographer Mark Serreze, the director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center and an author on the report’s precipitation chapter. The Arctic is already seeing an uptick in rain-on-snow events, and their frequency is likely to increase, he said.

“What happens in the Arctic will not stay in the Arctic.”

The Arctic is the bellwether of the global climate system, Serreze said. Though the effects of climate change are more amplified near the poles, they also provide a “warning signal” to the rest of the world of what’s to come as the climate warms. “What happens in the Arctic will not stay in the Arctic,” he said.

Biome Breakdown

The effects of the Arctic’s disordered vital signs have reverberated through local ecological and human communities, too, according to the report.

As the Arctic gets wetter and warmer, plant communities are shifting. Arctic tundra vegetation is growing more, and Arctic shrubification—an increase in the cover, height, and biomass of tundra shrubs at the expense of lichen and moss species—is repainting the landscape. Average peak tundra greenness, a measure of overall vegetation, was the third highest in recorded history this year.

“The farthest-north vegetation is not going to have a place to go, so you’re losing a whole group of plants,” said Uma Bhatt, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and an author on both the tundra greenness and surface air temperature chapters. As more shrubs, willows, and alders move to higher latitudes, they replace other plant species that some animals, such as caribou, rely on for food.

Salmon populations have responded to climate change with extreme population variability, said Erik Schoen, a fisheries biologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s International Arctic Research Center and lead author of the Alaska salmon chapter. Chinook and chum salmon have hit extremely low population levels in the past few years because of heat waves. Sockeye salmon, on the other hand, have boomed, taking advantage of warmer temperatures.

Rural Yukon communities commonly hunt, fish, and gather their own food, and the recent decline in chum and Chinook salmon has been devastating, Schoen said. “There have just been incredible effects on rural and Indigenous communities.”

“The changes that are unfolding are happening faster than our ability to quite understand them.”

Polar Probes Needed

For some of the authors, this year’s report card shows a great need for more scientific inquiry into the Arctic’s physical processes, the impacts of climate change, and how to predict future effects on Arctic residents. “The problem is that the changes that are unfolding are happening faster than our ability to quite understand them,” Serreze said. “We’re frantically trying to keep up.”

Permafrost beneath the ocean, for example, could drive ocean chemistry and global temperatures through the release of planet-warming gases. But there’s not much data on how much of the Arctic’s 2.5 million square kilometers (956,000 square miles) of undersea permafrost has thawed, whether there are gases trapped beneath the ocean, what that gas may be made of, and the climate consequences of those factors, Overduin said.

“We need to galvanize the political will to make a change.”

Meier said plenty of research gaps remain regarding the role of Arctic sea ice extent in regulating global temperatures, as well as how to best forecast ice cover.

The report highlights the role of Indigenous communities in helping to answer scientific questions; for example, Iñupiaq observers are documenting environmental changes and their effects as part of the Alaska Arctic Observatory and Knowledge Hub.

But just more science alone “isn’t going to cut it,” Schoen said. Policymakers need to better consult the available science when making decisions, he said. Part of that will include ensuring that the Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic most affected by—and familiar with—ecosystem changes are involved in decisionmaking.

Other authors also called for faster action from policymakers to cut greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel use, major contributors to climate change. “We need to galvanize the political will to make a change,” Bhatt said.

—Grace van Deelen (@GVD__), Staff Writer