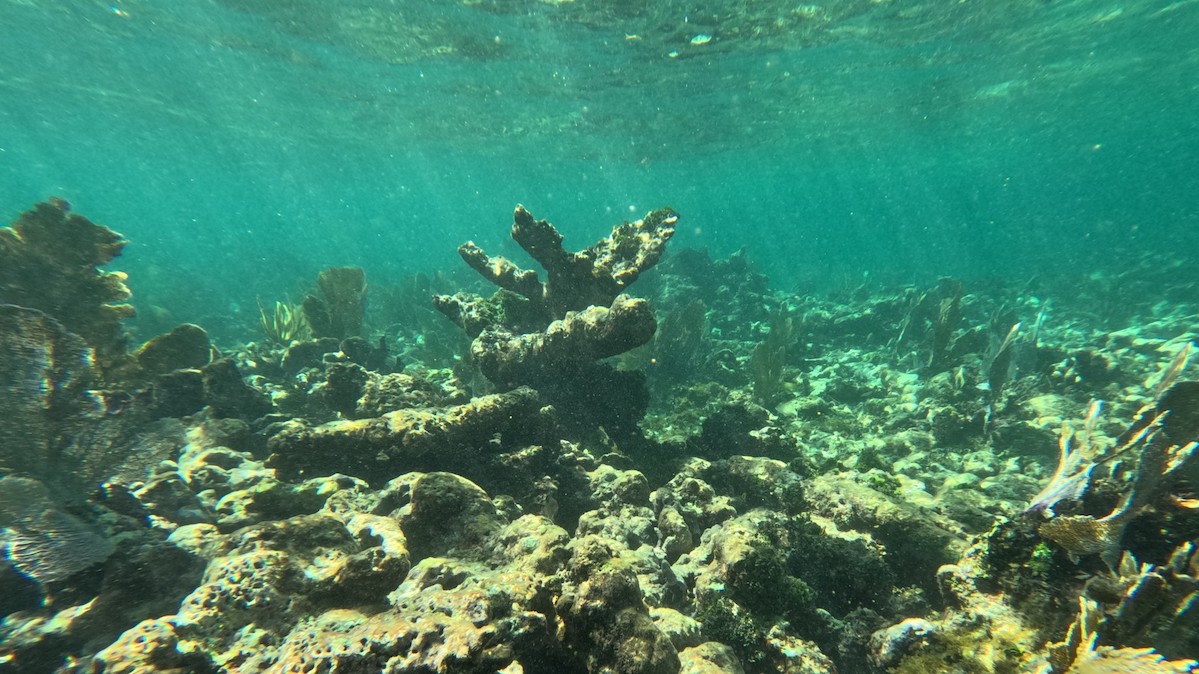

Coral reefs face myriad challenges, from ocean acidification to warming seas to destructive fishing activities. Sometimes, reefs can rebound from these ecological harms—but only if the coral species assembled on a reef can maintain the required growth rates.

A revised estimate of coral growth rates, published in Nature, suggests that tropical western Atlantic reefs are losing their capacity to build upward. Without upward reef growth, rising seas threaten to drown these reefs and cancel out the benefits they offer to coastal communities, such as minimizing flood damage. Researchers found that reef growth rates at essentially all the 400 sites analyzed won’t be enough to keep up with sea level rise by 2100.

“It’s very critical that we get a handle on what these rates are to be able to adequately gauge the scale of the problem,” said Cody Clements, a coral reef ecologist at the Georgia Institute of Technology who was not involved in the new study. “We have a lot of work ahead of us.”

“Unfortunately, the estimates are worse than before,” said Rich Aronson, a coral reef ecologist at the Florida Institute of Technology who was not involved in the new paper but works closely with its authors.

Eroding Reefs

Coral reefs grow when corals secrete calcium carbonate, a hard material that forms their exoskeletons.

Scientists can use knowledge of the species that make up a coral reef to estimate its vertical stacking porosity—how much vertical space a reef can build with a given amount of calcium carbonate.

The skeletons of branching corals, for example, tend to accumulate in an arrangement with more empty space, leading to more upward growth than other corals, such as flat corals, might achieve with the same amount of calcium carbonate.

However, the relationship between coral assemblage and vertical growth ability has so far been poorly defined, said Chris Perry, a coastal geoscientist at the University of Exeter and lead author of the new study.

Perry and his research group wanted a better estimate. They gathered 66 images of fossilized coral reefs from the tropical western Atlantic and analyzed how those reefs grew over time on the basis of the species of corals within. Then, they applied their revised estimates of growth to previously collected data on the ecology and carbonate production of 400 sites at three reef systems in the tropical western Atlantic: the Mexican Mesoamerican Reef, the Florida Keys, and Bonaire.

The studied reefs “are going to have zero capacity, really, to be able to track future sea level rise.”

The adjusted estimate of growth revealed a bleaker picture of reef health than the scientists anticipated: Researchers found that on average, reefs at all sites were growing at a sluggish pace—less than 1 millimeter per year—with an average growth rate decline of 12.4% when compared to previous estimates. On average, global sea levels are rising by about 4.5 millimeters per year.

The new calculations are particularly stark for reefs dominated by branching coral species, Didier De Bakker, a coral reef ecologist at the University of Exeter and a coauthor of the new study, wrote in an email.

If corals can’t grow, they shrink, falling victim to erosion by other marine creatures such as fish and sea urchins. Eventually, corals unable to keep up with sea level rise are drowned, unable to access sufficient light to continue growing at all.

The studied reefs “are going to have zero capacity, really, to be able to track future sea level rise,” Perry said.

In general, the new estimates of the link between assemblage type and vertical growth “revise our estimate downward” of how well corals will be able to keep up with sea level rise, Aronson said. The results also align with a 2023 study by Aronson and others that found reef growth in Panama’s Gulf of Chiriquí, part of the Pacific Ocean, is likely already unable to keep up with sea level rise.

Perry and De Bakker hope the data in the new study will feed into future studies modeling coastal wave exposure. “These new estimates provide a more realistic basis for projecting the vulnerability of adjacent habitats and reef-fronted urban areas,” De Bakker wrote.

Aronson said one next step for the research would be to apply the research team’s new estimates of vertical growth to reefs elsewhere, such as those in tropical Indo-Pacific waters. There, more species of branching coral still survive, giving Indo-Pacific reefs a slightly better chance of keeping up with sea level rise, said Clements, who studies Indo-Pacific reefs.

Climate Change and Corals

As a last step to their study, the researchers used what they’d learned about reef growth at 400-plus reef sites along with various future climate warming scenarios, called Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, or SSPs, to project how reef growth rates may change as the climate warms and sea levels continue to rise.

Results predicted that more than 70% of tropical western Atlantic reefs will transition into net erosional states by 2040 under an optimistic scenario (SSP1-2.6). But if warming exceeds SSP2-4.5 (a middle-of-the-road scenario in line with current development patterns), nearly all reefs will be eroding by 2100.

“Even if you go by some of the conservative estimates that they’re using, we still have a major problem in terms of coral reef accretion rates,” Clements said.

Reef Benefits Wash Away

Slower vertical growth means corals will have a tougher time maintaining their crest, or high point. These crests serve as wave breakers that dissipate wave energy and reduce flood damages to coastal communities. One estimate suggests that coral reefs near the U.S. coastline prevent more than $1.8 billion in damage each year.

As coral growth fails to track with sea level rise, these crests fall below the water’s surface. In turn, rising seas and waves from storms face less resistance, and reefs’ protective abilities get washed away.

“It’s quite difficult to see how we turn this around without really, really aggressive action on greenhouse gas emissions.”

Reef restoration is an active area of research, with engineers and ecologists working together to create various solutions, from LEGO-like scaffolding for corals to robots that sprinkle warming reefs with cool water. Previous research by Aronson and others indicated that successful restoration could help reefs keep pace with future sea level rise.

However, restoration will be effective only if it is done in tandem with efforts to rein in climate warming, which could slow sea level rise and reduce the frequency of marine heat waves, Perry said. “It’s quite difficult to see how we turn this around without really, really aggressive action on greenhouse gas emissions.”

“We have to do something about these global-scale stressors, like climate change, or it’s not going to matter,” Clements said.

—Grace van Deelen (@gvd.bsky.social), Staff Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.