By midcentury, outbreaks of cholera may worsen and move inland as climate change continues.

Researchers studying disease already agree that as temperatures warm and the climate becomes more unpredictable, populations around the world will most likely see more and more cholera outbreaks. Now, using climate models, satellite data, and known patterns in the spread of disease, scientists have started to estimate when and where outbreaks may arise.

Epidemics of cholera, which occur sporadically and with little warning, are specifically associated with high air temperatures and higher than average rainfall—the exact conditions associated with climate change, explained Rita Colwell, professor of computational biology at the University of Maryland. Colwell and her research group presented their results at a 15 December press conference at the 2014 American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco, Calif.

“For epidemic cholera, what we are seeing is [that] new and unexpected regions, particularly in Asia and Africa, are likely to experience this form of disease,” said Antar Jutla, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at West Virginia University and a member of the team that developed the prediction model of outbreaks.

With hotter temperatures and increased precipitation, the waterborne disease can spread more readily inland, into areas of denser populations, the researchers said.

Modeling Cholera’s Spread

Cholera is caused by a bacterium, spread via water systems, that induces diarrhea and vomiting; it can quickly lead to death by dehydration. Although the disease is easily treatable if caught early, poor infrastructure and high populations in more severely affected areas make the disease difficult to fend off.

The prevalence of endemic cholera—widespread, regular occurrences of the disease—manifest as two peaks: one during the dry season in the spring, when coastal regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America experience regular outbreaks, and the other later in the year, during the wet season, when flooding flushes the disease-causing bacterium upriver and inland toward high-density populations. Satellite data have helped scientists hone in on fine details involving the seasonality of the disease, explained Ali Akanda, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Rhode Island.

Measuring environmental factors such as surface temperature and precipitation rates via satellite and correlating these data with records of cholera outbreaks helped the researchers create a model that could predict outbreaks of cholera months before the onset of particular events, such as seasonal monsoons. Now, by combining these models with climate models, scientists can observe how sudden outbreaks of cholera may affect new regions—especially those farther inland—in the coming decades.

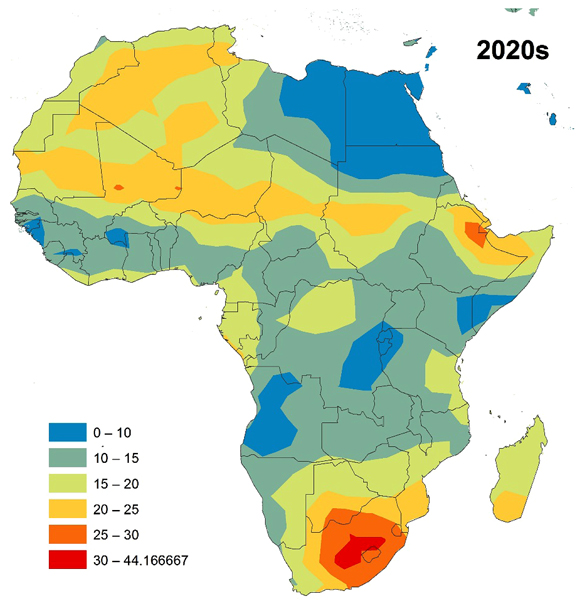

For example, findings focused on Africa are displayed in the maps to the left, which show the strength (in percent) of the combination of temperature and precipitation that may amplify the prevalence of cholera as climate changes. Researchers tentatively say that red areas may see sharp increases in cholera outbreaks by midcentury.

The results are based on the scientists’ own models about what environmental factors affect the spread of cholera, combined with climate models from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Max Planck Institute.

A Paradigm Shift

The predictions are extremely preliminary, Akanda explained. While they anticipate the spread of cholera to new, inner regions of Africa and Asia, these results should not be used to definitively say where the disease is headed. Rather, they represent scenarios that public health and governmental officials should consider when evaluating how climate change will make populations more vulnerable to disease.

The next step will be to gather societal data about how populations move, interact, and react to the spreading disease, Akanda explained.

“I think that this is a paradigm shift in our interpretation of cholera epidemiological data,” said Colwell, “and for the first time, hydrological, climatological data [are] being incorporated in understanding the outbreaks.”

—JoAnna Wendel, Staff Writer

Citation: Wendel, J. (2015), Climate change predicted to worsen spread of cholera, Eos Trans. AGU, doi: 10.1029/2015EO021463

Text © 2014. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.