To understand Earth’s remote past, paleontologists and geologists look for vestiges of history hidden in rocks. They also look for clues of life in less obvious materials such as ages-old charcoal, which can reveal how the global environment changed in the deep past and give a glimpse of how it might change in the distant future.

Recently, a team of researchers from Brazil, Germany, and India identified rare charcoal records of paleowildfires in the Saurashtra Basin in Gujarat, northwestern India. The material, said lead author Gisele Sana Rebelato, dates back to the Early Cretaceous (145–100 million years ago), a time when the supercontinent Gondwana was drifting apart. The paper was published in Current Science earlier this year.

“Whenever we talk about South America, Africa, Antarctica, India, and Australia, we’re talking of our geological ‘backyard,’ as they were all together in Gondwana,” said coauthor André Jasper, who works with Rebelato at the University of Vale do Taquari (Univates) in Brazil.

“For fire to have been an evolutionary driver, it must have occurred globally, not just in isolated places.”

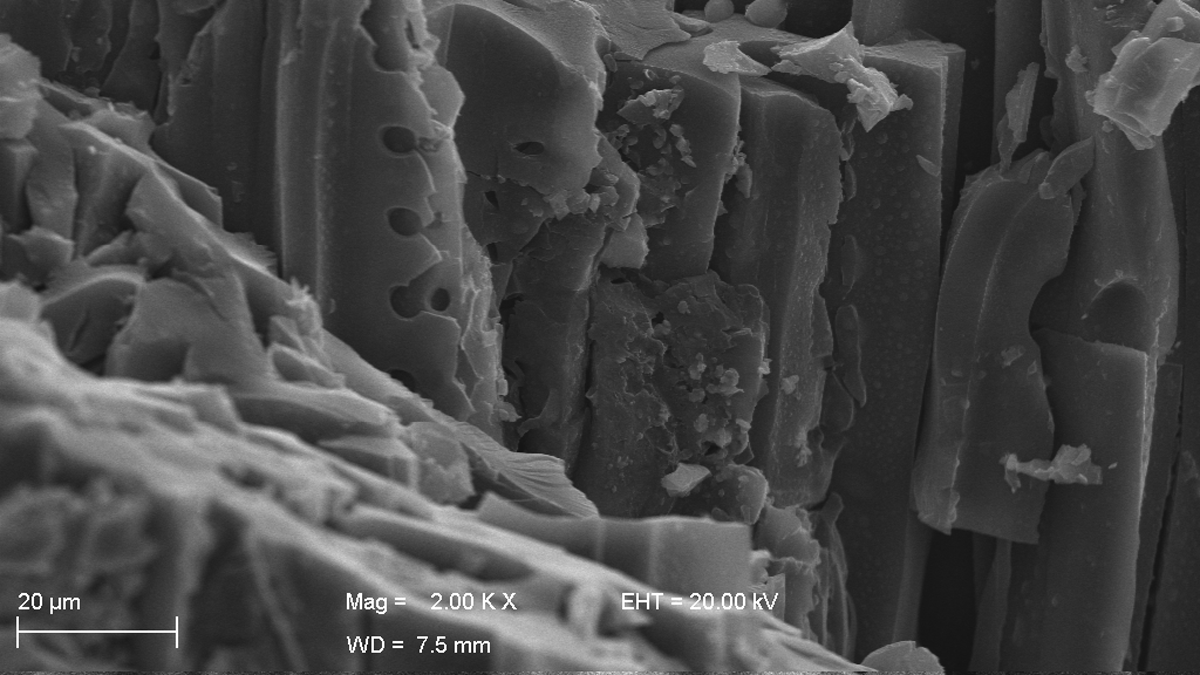

In analyzing the charcoal with both a stereomicroscope and a scanning electron microscope, the team identified charred wooden remains of gymnosperms, the flowerless plants such as conifers and cycads that dominated Earth until the Cretaceous, when they were outcompeted by angiosperms. “It was during this period,” Rebelato explained, “that angiosperms, or flowered plants, emerged and expanded, in part because of fire-altered biological dynamics. As [angiosperms] had a quite short life span, one of the hypotheses is that wildfires ended up favoring them, as they grow and recover quickly.”

The new research did not definitively confirm that hypothesis, in part because it lacked fossilized plants to analyze. “When we look at charcoal, we’re normally looking at wooden structures, which is what can actually fossilize. And [during the Late Cretaceous] angiosperms were mostly herbaceous; they didn’t have wood that could be preserved. So it’s hard to make any straight correlations for now,” Rebelato said.

The study, however, advances science another rung on the ladder of understanding paleowildfires as global phenomena. “There were wildfires in other regions, such as Eurasia and the Americas. For fire to have been an evolutionary driver, it must have occurred globally, not just in isolated places. So every study of this kind adds more evidence to that—and there are few descriptions from Gondwana,” Jasper said.

Wildfire as Part of a Broader Earth System

According to Joseline Manfroi, a paleobiology researcher at the Chilean Antarctic Institute, the new study is important to the geosciences because the Cretaceous “represents a crucial moment in Earth’s geological history, having been the stage for significant environmental and geological changes across the globe. [Scientific] work that analyzes the elements that witnessed these changes, such as fossil records, enables a better understanding of the Earth system as a whole.”

Paleowildfires during the Cretaceous in places like Antarctica and Patagonia, Manfroi said, point to “significant climate and environmental changes that climaxed in one of the Earth’s great extinctions but also show the relevance of fire to the evolution of vegetal groups that dominate terrestrial environments today, such as the angiosperms.”

Manfroi, who has worked with the Brazilian authors before but did not take part in this study, said the study of paleowildfires helps us understand “not just the frequency and environmental conditions in which these phenomena occurred, but above all the relation of fire as a perturbing and changing agent for different ecological niches in the past. [Fire] contributed to configure the diversity and biogeography of flora in different latitudes of the globe.”

Ancient wildfires “aren’t just localized, destructive, natural events but are also an integral part of the broader Earth system.”

Paleobotanist Ian Glasspool, a research associate in geology at Colby College, said ancient wildfires “aren’t just localized, destructive, natural events but are also an integral part of the broader Earth system.”

Their list of impacts is extensive, Glasspool explained, ranging from deep feedback on the global carbon cycle to influences in nearshore marine sedimentology through changes in runoff and erosion. Wildfire has a “feedback role in stabilizing the Earth’s atmospheric oxygen concentration” and acts “as a ‘global herbivore’ through its impacts on vegetation. [It] preserves organic material; charcoal produced by fires is chemically inert, structurally rigid, and may preserve exquisite cellular, and even subcellular, three-dimensional anatomy,” said Glasspool, who did not take part in the study.

The study of ancient wildfires “has become an integral factor in modeling Phanerozoic atmospheric oxygen concentration, for example. Fire may perturb ecosystems, particularly where peats are burned; the resultant tree mortality can be extreme,” Glasspool continued.

“Unfortunately,” Jasper warned, “the planet is burning right now. And we’re mapping this kind of event across time and see [that] the consequences on life and biodiversity are not to be taken lightly.… These [wildfire] events were followed by mass extinctions.”

“The problem is that we’re accelerating a process that would take thousands or hundreds of thousands of years to happen,” added coauthor Ândrea Pozzebon-Silva, also a researcher at Univates. “If reduced to centuries or decades, the effects of wildfires can be deleterious to humans and Earth’s biodiversity at a scale not seen before.”

—Meghie Rodrigues (@meghier), Science Writer