Farming practices of the Vikings and their ancestors could provide inspiration for resilient food systems today. That’s thanks to a study exploring how Scandinavian societies adapted their agricultural activities in a period of European history marked by stark climate fluctuations.

The Viking Age kicked off around 800 as societies in Scandinavia expanded, partly as a result of a rise in temperature that allowed agriculture to flourish. Historians believe that a growth in population and the pressure it placed on available farmland were reasons why Vikings began venturing beyond their homelands.

In popular culture today, a lot of focus is placed on Viking raids and attacks on religious sites, partly because many firsthand accounts were written by besieged Christian scholars. But archaeological evidence suggests that above all else Vikings were agriculturalists who cultivated crops and reared livestock, often on self-sufficient farms.

Less is known about farming practices in pre-Viking societies, those existing in an era known as the Dark Ages Cold Period. During this half millennium between 300 and 800, northern Europe experienced cold climates driven by volcanoes spewing gases and dust into the atmosphere, which reduced the amount of solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface.

Digging in the Mud Near Rakni’s Mound

The new research finds evidence that a community in Norway responded to this climate turbulence by regularly adapting its cereal production and animal husbandry practices. It is one of the first studies from a multidisciplinary project called Volcanic Eruptions and their Impacts on Climate, Environment, and Viking Society in 500–1250 CE (VIKINGS).

“Our findings demonstrate that climate already changed in the past—it is not something new—and societies had to adapt to it already 1,500 years ago.”

“Our findings demonstrate that climate already changed in the past, it is not something new, and societies had to adapt to it already 1,500 years ago. This shows that we also have to adapt to the rapid climate change we observe today in order to maintain and improve our food production,” said Manon Bajard of the University of Oslo, who presented the research in April at the 2021 general assembly of the European Geosciences Union.

Bajard’s team analyzed sediments from Lake Ljøgottjern in southeastern Norway. Lake Ljøgottjern is located next to Rakni’s mound, one of the largest barrows in northern Europe. Previous archaeological studies have dated the mound’s construction to the mid-6th century and found extensive evidence of farming and food preparation activities in the area.

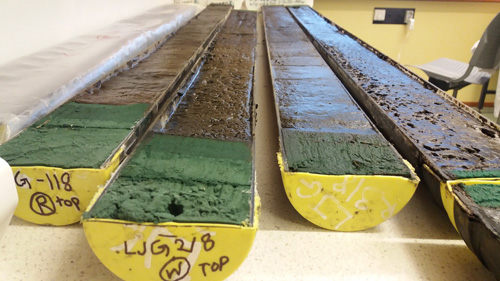

Bajard and her colleagues steered a raft to Ljøgottjern’s deepest section, where lake bed sediments are least affected by lateral flows. By lowering a weighted tube, the team retrieved a 6-meter sediment core. Muds have been accumulating at Lake Ljøgottjern since the last glacial retreat more than 10,000 years ago, so the sediments contain clues about the area’s history.

To analyze the core, Bajard’s group used carbon-14 dating to identify the section corresponding to 300–800. Past temperature fluctuations were reconstructed from calcium deposits: During warmer periods, there was more biotic activity in the lake, which resulted in a greater accumulation of calcium carbonate deposits on the lake bed.

The key finding was that warmer phases were dominated by the cultivation of crops, whereas cooler phases were dominated by livestock farming. Manon’s team, as well as archaeologists working at Rakni’s mound, suggest that it is, perhaps, not surprising that farmers would rely more on animals during colder periods (when crop yields are reduced) and are reexamining archaeological evidence to support this theory.

Pollen grains in the core revealed the types and extents of staple crops, which included rye, wheat, and barley. Overall, cold periods corresponded to reduced crop yields, with barley being the most affected by climate shifts.

Animal grazing near the lake was inferred from the core’s quantity of Sordaria, fungi that thrive on animal feces. Small quantities of DNA recovered from the core also revealed the presence of cows, pigs, and sheep.

Strategic Farmers

Bajard said Viking ancestors may have strategically prioritized the best land close to the community for crops. During warmer periods when harvests were more robust, animals were relocated to areas less suitable for crops, perhaps land that was still forested.

“Later, during the Viking Age and Middle Ages, both activities were occurring at the same time, but it was much warmer then, so the cultivation area could have been extended,” Bajard said.

“Over generations, hard-won experience taught a farmer what works and [that] experiments could be fatal.”

To build a more complete picture of how farming practices evolved, Bajard’s team will try to collect more DNA samples from near the lake to start quantifying how the mix of animal types varied over time.

Peter Hambro Mikkelsen, an environmental archaeologist at Aarhus University in Denmark not involved in the VIKINGS research, said food producers today might learn from this community’s ability to diversify. “Over generations, hard-won experience taught a farmer what works and [that] experiments could be fatal. As opposed to modern farming where specialization is the key to large-scale production, traditional agriculture KNOWS that when weather fails, livestock can perish—and the enemy can be at the gates of one’s village.”

—James Dacey (@JamesDacey), Science Writer

Citation:

Dacey, J. (2021), Food security lessons from the Vikings, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO160342. Published on 29 June 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.