In 2019, predictions indicate that the Gulf of Mexico will retain the dubious distinction of having the second-largest low-oxygen dead zone on Earth (the Baltic Sea remains firmly in first place). By the end of the summer, the hypoxic region on the seafloor at the mouth of the Mississippi River is expected to occupy over 22,000 square kilometers—an area the size of the state of Massachusetts.

“The dead zone is driven by nitrogen and phosphorus runoff from agricultural operations that finds its way into the watershed and then into the Gulf.”

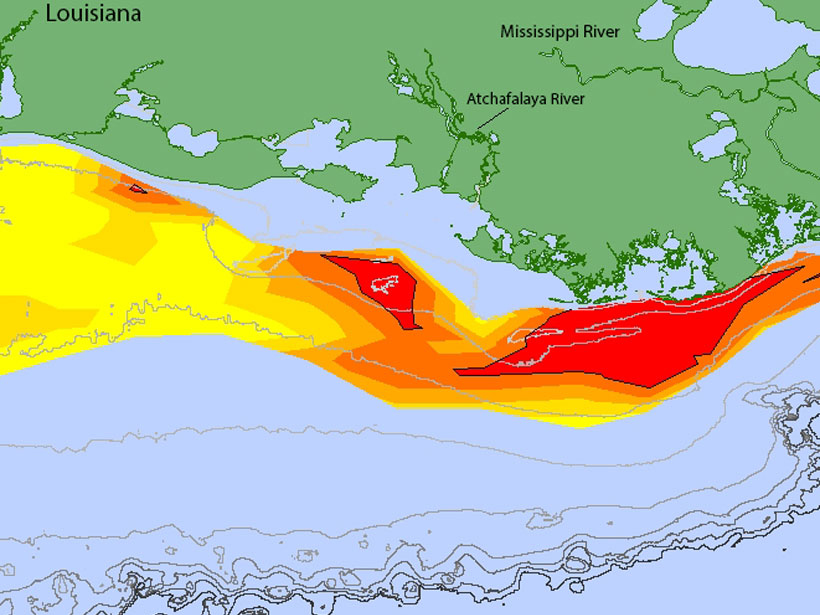

The hypoxic zone, with oxygen levels less than 2 parts per million, forms every summer on the seafloor just off the coast of Texas and Louisiana, where the Mississippi and Atchafalaya watersheds drain into the Gulf of Mexico.

The dead zone probably started forming in the 1970s when farmers started applying more nitrogen-based fertilizers to crops across the Midwest, says Eugene Turner, an oceanographer at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and coauthor of the new forecast, released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as part of a larger series of studies on the health of the Gulf.

“The dead zone is driven by nitrogen and phosphorus runoff from agricultural operations that finds its way into the watershed and then into the Gulf,” Turner says. The excess nutrients stimulate algae growth, and the decomposition of this algae on the seafloor leads to widespread hypoxic conditions.

Runoff and Rainfall

The new forecast models by Turner and his wife and coauthor, Nancy Rabalais, take into account the discharge rates of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers as well as U.S. Geological Survey estimates of the amounts of nitrate and phosphate being carried by the rivers. In the month of May alone, 156,000 metric tons of nitrate and 25,300 metric tons of phosphorus were deposited into the Gulf of Mexico.

This year’s record-setting size is also due to the unusually high amounts of rainfall that flooded many parts of the Midwest this spring. The more rainfall there is, the higher the river flow is, which carries more nutrient runoff into the Gulf.

Turner and Rabalais have been conducting systematic survey cruises to map the Gulf dead zone since 1985. This year the cruise will sail the last week in July, when the dead zone usually begins peaking in size. The forecasts help guide the systematic survey cruises.

If a hurricane or large storm hits the Gulf before or during a cruise, the temporary mixing of the water column can make the dead zone appear smaller, says Katja Fennel, a biogeochemical oceanographer at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, who is also a contributor to the larger NOAA-funded Gulf project.

“If you have a year with several big storms or hurricanes, they can disrupt the stratification of the water column and reoxygenate the bottom water,” Fennel says. “But the mixing is only temporary: A few weeks later, hypoxia will be reestablished.”

Mobile organisms like shrimp and fish tend to migrate out of the hypoxic zone, and the forecasts can also be used to plan shrimping and fishing expeditions in the Gulf, says Robert Hetland, a physical oceanographer at Texas A&M University in College Station who is not involved in the NOAA studies. “We don’t have a clear understanding yet of how hypoxia affects mortality rates, but there is some indication that it may affect the growth rates of some Gulf organisms,” resulting in smaller shrimp, he says.

Land Use

In 1997, the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force (also known as the Hypoxia Task Force) was established with the mission of reducing the size of the Gulf dead zone to less than 5,000 square kilometers, but so far, little progress has been made, Turner says.

“Land use practices can evolve with benefit to the nation, farmers, farmland, and the Gulf, but it will take time and persistence and good will.”

“The only way to accomplish that goal is to reduce the nitrogen loading into the Mississippi,” he says. “In agriculture, there’s a lot of resistance towards changing land use practices. Farmers are embedded in an economic and political structure that makes it very difficult to change practices without serious economic consequences.”

So far, fertilizer load reductions in the United States have been voluntary with no mandated regulations. In Europe, mandatory limits were enacted about 15 years ago on rivers such as the Rhine.

“European rivers have been cleaned up quite dramatically, and coastal eutrophication is less of an issue in European waters,” Fennel says. “So it is possible to reverse these trends, but relying on volunteer efforts is not the most effective way to do it.”

“It is going to take a lot to change what has developed over 2 centuries,” Turner says. “Land use practices can evolve with benefit to the nation, farmers, farmland, and the Gulf, but it will take time and persistence and good will.”

—Mary Caperton Morton (@theblondecoyote), Science Writer

Citation:

Morton, M. C. (2019), Gulf dead zone looms large in 2019, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO128019. Published on 11 July 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.