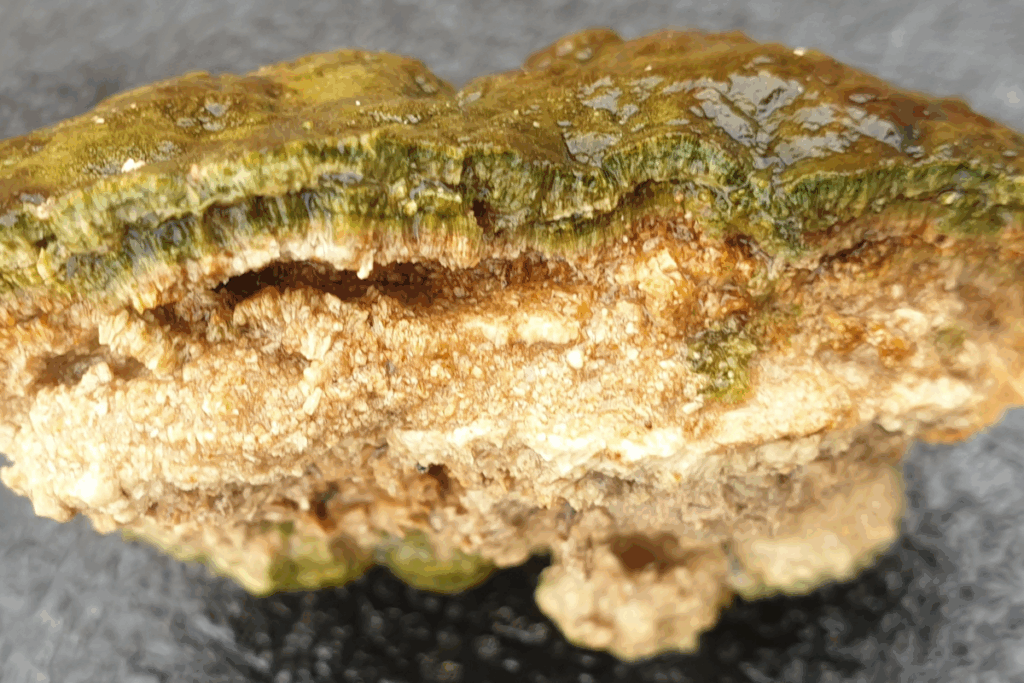

On every continent, unassuming rocks covered in a thin, slimy layer of microbes pull carbon from the air and deposit it as solid calcium carbonate rock. These are microbialites, rocks formed by communities of microorganisms that absorb nutrients from the environment and precipitate solid minerals.

“We’re going to learn some critical information through this work that can add to our understanding of carbon cycling and carbon capture.”

A new study of South African coastal microbialites, published in Nature Communications, shows these microbial communities are taking up carbon at surprisingly high rates—even at night, when scientists hypothesized that uptake rates would fall.

The rates discovered by the research team are “astonishing,” said Francesco Ricci, a microbiologist at Monash University in Australia who studies microbialites but was not involved in the new study. Ricci said the carbon-precipitating rates of the South African microbialites show that the systems are “extremely efficient” at creating geologically stable forms of carbon.

The study also related those rates to the genetic makeup of the microbial communities, shedding light on how the microbes there work together to pull carbon from the air.

“We’re going to learn some critical information through this work that can add to our understanding of carbon cycling and carbon capture,” said Rachel Sipler, a marine biogeochemist at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Maine. Sipler and her collaborator, Rosemary Dorrington, a marine biologist at Rhodes University in South Africa, led the new study.

Measuring Microbialites

Over several years and many visits to microbialite systems in coastal South Africa, Sipler and the research team measured different isotopes of carbon and nitrogen to study the microbial communities’ metabolisms and growth rates. They found that the structures grew almost 5 centimeters (2 inches) vertically each year, which translates to about 9–16 kilograms (20–35 pounds) of carbon dioxide sequestered every year per square meter (10.7 square feet) of microbialite.

Results showed the microbialites absorbed carbon at nearly the same rates at night as they did during the day. Both the nighttime rates and the total amount of carbon precipitated by the system were surprisingly high, Ricci said.

“Different organisms with different metabolic capacities work together, and they build something amazing.”

The traditional understanding of microbialite systems is that their carbon capture relies mostly on photosynthesis, which requires sunshine, making the high nighttime rate so surprising that Sipler and the team initially thought it was a mistake. “Oh, no, how did we mess up all these experiments,” she remembers thinking. But further analysis confirmed the results.

It makes sense that a community of microbes could work together in this way, Ricci said. During the day, photosynthesis produces organic material that fuels other microbial processes, some of which can be used by other organisms in the community to absorb carbon without light. As a result, carbon precipitation can continue when the Sun isn’t shining.

“Different organisms with different metabolic capacities work together, and they build something amazing,” Sipler said.

Future Carbon Precipitation

The genetic diversity of the microbial community is key to creating the metabolisms that, together, build up microbialites. In their experiments, the research team also found that they were able to grow “baby microbialites” by taking a representative sample of the microbial community back to the lab. “We can form them in the lab and keep them growing,” Sipler said.

The findings could inform future carbon sequestration efforts: Because carbon is so concentrated in microbialites, microbialite growth is a more efficient way to capture carbon than other natural carbon sequestration processes, such as planting trees. And the carbon in a microbialite exists in a stable mineral form that can be more durable across time, Sipler said.

Additional microbialite research could uncover new metabolic pathways that may, for example, process hydrogen or capture carbon in new ways, said Ricci, who owns a pet microbialite (“very low maintenance”). “They are definitely a system to explore more for biotechnological applications.”

Sipler said the next steps for her team will be to continue testing the microbial communities in the lab to determine how the microbialite growth rate may vary under different environmental conditions and to explore how that growth can be optimized.

“This is an amazing observation that we and others will be building on for a very long time,” she said.

—Grace van Deelen (@gvd.bsky.social), Staff Writer