A translation of this article was made possible by a partnership with Planeteando. Una traducción de este artículo fue posible gracias a una asociación con Planeteando.

When record-breaking temperatures and heat domes envelop swaths of the United States each summer, people across the country experience these extreme heat events differently. Those living in historically redlined neighborhoods, where discriminatory land use and housing policies caused segregation and racism to flourish, are still, even today, at higher risk for hotter temperatures and the health effects caused by heat stress.

In a new study published in One Earth, researchers showed that heat stress disproportionately affects poor and non-white residents in 481 American cities. “We found that the actual disparity was pretty consistent across cities: In over 90% of the cities we considered, we found both income and race-based inequalities in heat exposure,” said TC Chakraborty, an Earth scientist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and lead author of the study. This type of information can help city leaders to use better measures of heat disparities as well as to protect the populations most at risk from heat exposure.

The Danger of Unrelenting Heat

Urban heat islands, hot pockets of city where asphalt, dense buildings, and infrastructure cause the temperature to rise higher than in surrounding areas, are home to millions of people who are not able to properly escape the effects of unrelenting summer heat.

Chronic exposure to excessive heat has an impact on cardiovascular, respiratory, and mental health.

“People who live in an urban area tend to walk to do their daily tasks. It’s one of the great things about living in a city, that things are close by and you can use public transportation, but that also means you have to spend more time outdoors,” said Neelima Tummala, a physician and codirector of the Climate Health Institute at George Washington University, who was not involved in the study.

In neighborhoods without parks or mature trees, where asphalt and dense buildings absorb and radiate the summer heat, residents may find it difficult to escape extreme temperatures both indoors and outside. That type of continuous exposure can be very dangerous. The body becomes unable to cool itself properly through sweating. Chronic exposure to excessive heat has an impact on cardiovascular, respiratory, and mental health, Tummala said. “Long-term exposure to higher nighttime temperatures may affect your sleep quality and your mental and heart health,” she said. “You’re constantly at an elevated temperature that your body has to address.”

Mapping Heat Disparity

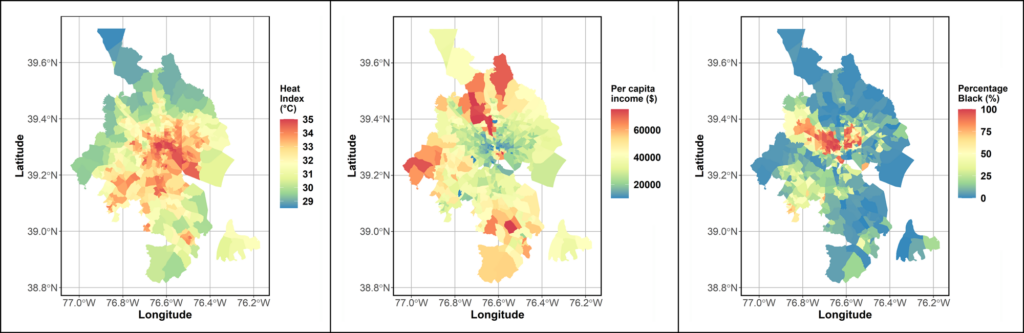

Previous studies on urban heat have used satellite data to estimate land surface temperatures. Chakraborty and his colleagues instead evaluated heat stress using the U.S. National Weather Service’s heat index and the Meteorological Service of Canada’s humidity index (humidex), which combine air temperature and humidity to better describe what heat feels like. Using models that combined these variables was a more accurate way to catalog heat stress across American cities between 2014 and 2018.

Mapping heat indices onto census data revealed that lower-income neighborhoods and residents of color experienced hotter temperatures and higher humidity, together amplifying heat stress. Census tracts with higher income saw less heat stress. Heat stress was also generally higher in tracts with a larger percentage of Black residents.

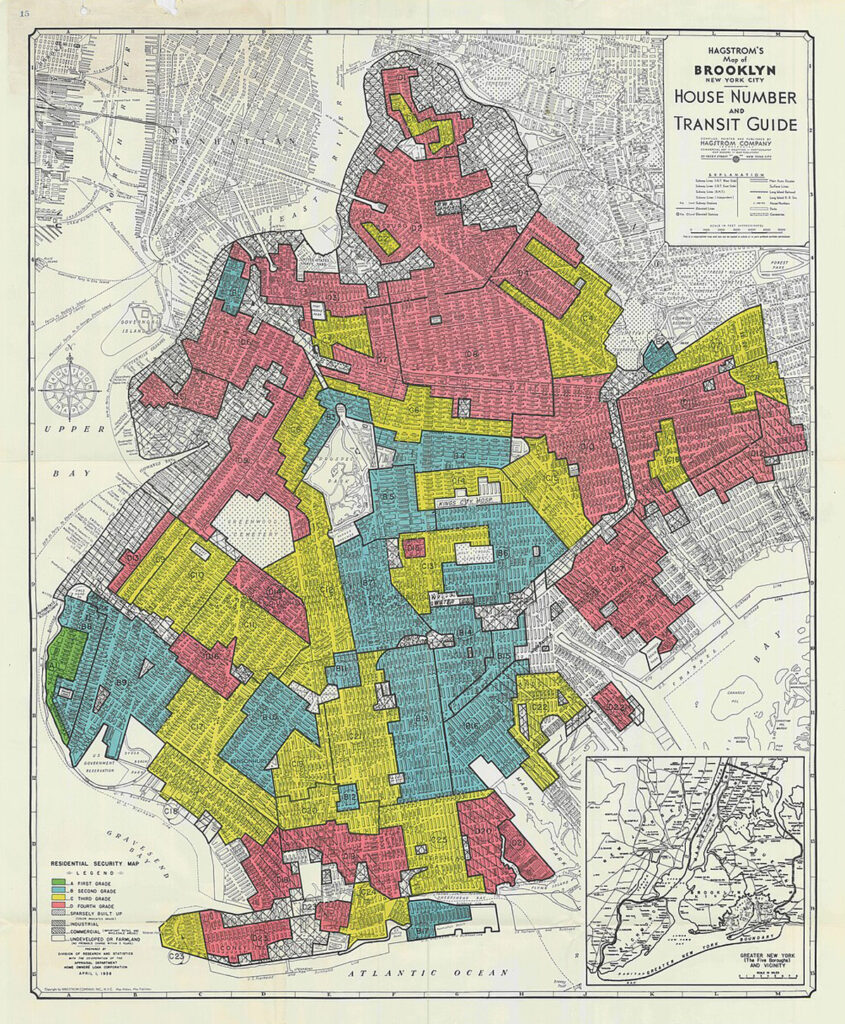

The researchers compared these findings to historical data in 177 cities to further note this income and race-based disparity over time. In the 1930s, the U.S. government graded neighborhoods for investment suitability. Many of the neighborhoods that were home to poor and minority populations, especially Black residents, were deemed riskier investments and therefore received less funding for development and homeownership programs. Today these redlined neighborhoods have far worse environmental conditions than other parts of their respective cities. They have less tree cover and experience higher surface temperatures than originally nonredlined neighborhoods.

The disparities were pervasive, Chakraborty said. Redlined neighborhoods, which lending programs generally graded D, had a higher heat index than A-graded neighborhoods. “This was a very interesting result—that this degree of inequality and segregation is related so strongly with the degree of heat disparity,” he said.

Protecting the Most Vulnerable

“Studies like this, that seek to further understand existing disparities in heat exposure, are important for identifying which communities are most at risk from climate change–related environmental changes such as worsening heat extremes,” Tummala said. Public health measures and mitigation strategies are needed to protect city residents most at risk from heat—especially as soaring temperatures become increasingly common.

“Areas with fewer street trees, less access to green space—that’s where you start to see the legacy of disinvestment and institutional racism that has come into play.”

“Areas with fewer street trees, less access to green space—that’s where you start to see the legacy of disinvestment and institutional racism that has come into play,” said Lara Whitely Binder, climate preparedness program manager for King County, Washington, who was not involved in the study.

Because the climate is changing, moving forward, cities must prepare for hotter summers and more frequent deadly heat waves through a variety of means—both indoors and outside. “We need to not only better understand where is it hot, but what are the socioeconomic factors for the people who live in those areas,” Whitely Binder said. “We can start to unpack what’s in the heat island and use that to start informing the policy decisions we’re going to make.”

—Rebecca Owen (@beccapox), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.