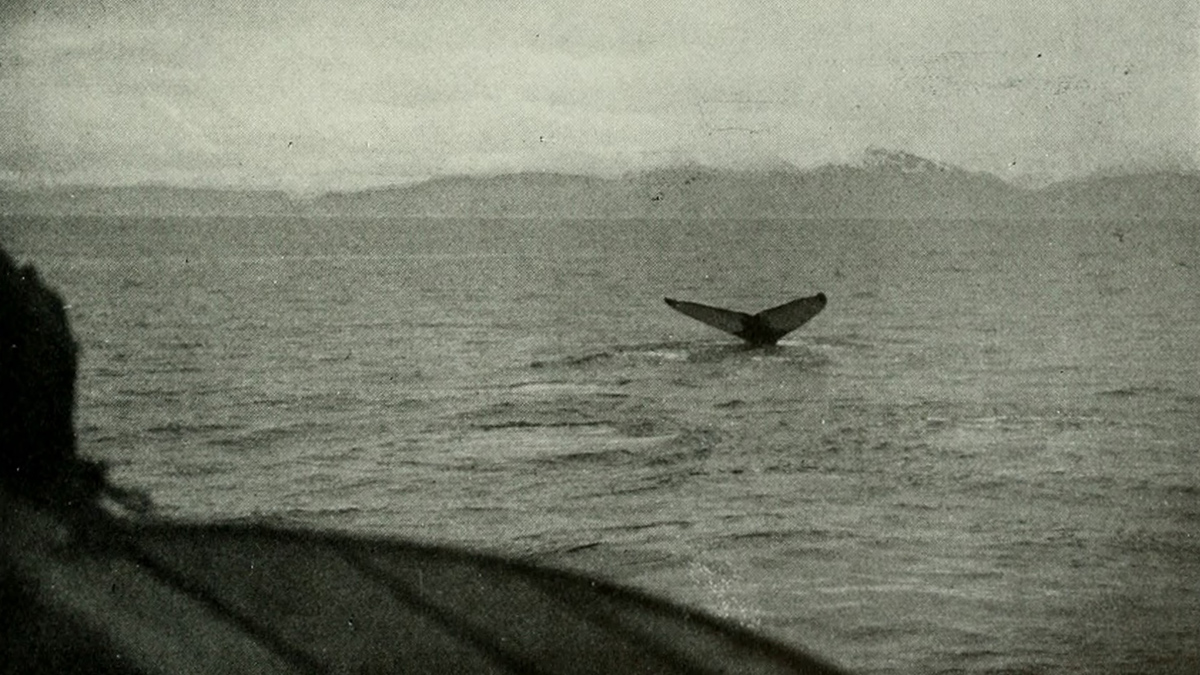

Industrial whaling was historically a grisly affair enacted with brutal efficiency. With an eye to harpooning as many whales as possible, whalers created detailed records intended to inform and improve future expeditions.

Those records, stretching back more than a century, provide rich datasets that scientists have used to answer questions about our planet’s past, including how sea ice surrounding Antarctica ebbed and flowed in the decades before satellites enabled continuous monitoring.

“I find it a paradox. We decimated them; now, they’re helping us to do a better job for our future projections.”

In a study published earlier this year in Environmental Research: Climate, a team of cetologists, oceanographers, and climate scientists dug deep into those records and used them to show that contemporary climate models overestimate the historic extent of sea ice in the Southern Ocean.

The group relied specifically on data from humpback whaling expeditions because that species tends to skirt along the ice edge in summer, skimming krill fed in turn by algal mats that form along the underside of the ice as it thins and retreats. This behavior makes the locations of humpback harvests a useful proxy for how far north sea ice could have reached.

“I find it a paradox,” said oceanographer Marcello Vichi of the University of Cape Town in South Africa. “We decimated them; now, they’re helping us to do a better job for our future projections.” Vichi is the first author of the new study.

Icy Estimation

Accurately estimating the extent of sea ice is important for modeling because ice reflects sunlight, said Marilyn Raphael, a physical geographer at the University of California, Los Angeles, who often focuses her research on Antarctic sea ice but was not involved with the new study.

“If it doesn’t do that reflection, the large-scale [latitudinal] temperature gradient changes,” Raphael explained, “and when the temperature gradient changes, the wind changes. And when the wind changes, the climate changes.”

Sea ice also insulates parts of the Southern Ocean, limiting how much heat the water absorbs from the atmosphere.

How climate models input the historical extent of sea ice shapes how they account for Earth’s energy balance prior to the onset of climate change. More accurate historic inputs also have implications for modeled predictions about the extent of sea ice in the future.

“If you can’t get it right when you know what happened,” Raphael said, “then you’ve got to worry about if you’ll get it right when you don’t know what will happen.”

Using Catch Data to Constrain Sea Ice

Vichi and his colleagues used data acquired from the International Whaling Commission, which recorded the locations of more than 215,000 humpback catches over the first half of the 20th century, with latitude and longitude logged to the nearest degree.

They focused their study on the 1930s, a period during which whalers logged consistently high catch counts for each month of the Antarctic summer (November through February), when humpbacks feed as ice retreats. This narrowed scope left the researchers with around 13,500 records to work with, of which more than 97% had trustworthy location data.

The team compared the catch locations with the climate models that are best tuned to match today’s satellite observation data.

All the models, they found, consistently overestimate the historic extent of sea ice by an average of about 4° latitude. In some places, Vichi added, they overshoot the ice edge suggested by the whaling records by 10°.

“It’s really great to examine historical data to find ways of understanding a complex system better, especially a complex system that we don’t have a lot of observations on.”

Vichi and his colleagues don’t yet know for certain what drives the discrepancy they found. One possible explanation may be that the nature of how ice forms and behaves in the Southern Ocean has shifted, potentially entering a new regime around the 1960s.

Scientists are working with fewer than 50 years of satellite observations when it comes to sea ice, “so if there are large cycles that happen, we don’t know if that 50 year period is representative of the whole,” said climatologist Ryan Fogt of Ohio University in Athens, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Given the dearth of direct observations, this gap can be filled only with proxies like catch data. Using indirect data is an approach both Raphael and Vichi acknowledge has limitations but is crucial for better understanding the nuances of climate change.

“I think using the whaling records is a good idea,” Raphael said. “It’s important to use all the information we have to see how it matches.”

“It’s really great to examine historical data to find ways of understanding a complex system better, especially a complex system that we don’t have a lot of observations on,” said Fogt, who has also worked with historical records (though not whale catch data) to reconstruct historic sea ice extent around Antarctica. “So even though they’re imperfect, these historical sources, they have value.”

—Syris Valentine (@shapersyris.bsky.social), Science Writer