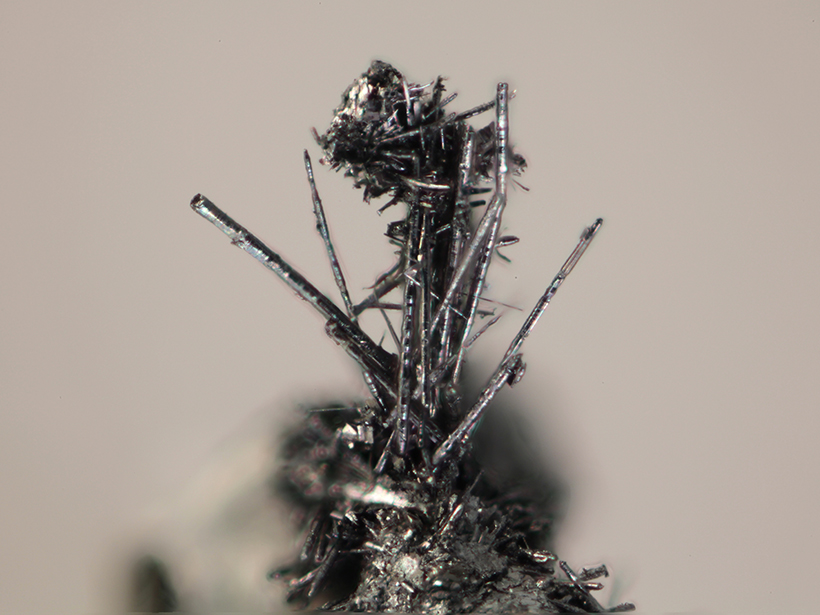

Software engineer Bob Simonoff didn’t realize that he was looking at a never-before-described mineral when he peered through his daughter’s microscope at a sample of tanzanite one day in 2011. Covering the blue mineral were tiny, wirelike black structures, nothing like the senior Simonoff, a mineral enthusiast, had ever seen.

His daughter, fellow mineral buff Jessica Simonoff (then 14 years old), was studying the sample of tanzanite for an internship at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D. C., with mineralogist Mike Wise.

Wise didn’t recognize the dark material either, so he and the younger Simonoff decided to look closer. In the lab, they found a high abundance of molybdenum in the wiry mineral, so they suspected it was an unusual form of molybdenite. Meanwhile, John Jaszczak, a solid-state physicist with a “serious interest in mineralogy,” spotted a news item about this oddly shaped mineral from an issue of Mineral News and wondered if it could be an undescribed mineral. He later requested a sample from Wise to study in his own lab at Michigan Technological University in Houghton.

Back at his lab, Jaszczak used Raman spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the mineral to investigate further. When light from a spectrometer bounces off a sample, the wavelengths of scattered photons reveal which kinds of atoms make up the material. The spectrum from this sample didn’t match any known minerals, Jaszczak said.

Further investigation with an electron microscope revealed that the crystal structure of the millimeter-sized dark wires contained molybdenum but also sulfur, lead, and other elements—a combination never seen before, Jaszczak said. This result was a big clue that the mineral could be deemed entirely new.

And it was. Jaszczak recently published a paper in the journal Minerals describing the find, for which he proposed the name merelaniite after its hometown of Merelani, Tanzania.

Road to a Name

Every new mineral candidate must be approved by the International Mineralogical Association’s (IMA) Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature, and Classification (CNMNC). Scientists submit their candidate material to a battery of tests and build a case for its novelty. To do so for merelaniite, Jaszczak sought help from scientists all over the world to determine the mineral’s crystal structure and properties such as density, opacity, and reflectiveness, among others.

Jaszczak sought help from scientists all over the world to determine the mineral’s crystal structure and other properties.

The CNMNC receives about 120 new mineral proposals each year, of which it approves about 100, said Peter Burns, IMA president and an environmental chemist at the University of Notre Dame in Notre Dame, Ind. Currently, IMA lists 5179 unique minerals, but only a few boast a curved structure like merelaniite’s, said Burns, including one called cylindrite.

As they investigated the new material, Jaszczak’s team learned that its oddly curving shape resulted from a pattern of alternating layers: one of mostly molybdenum disulfide, then two layers of predominantly lead sulfide, then molybdenum disulfide again, and so on. A mismatch of bonding lengths between atoms across layers causes the curvature as atoms try to match up, warping the mineral structure, Jaszczak said.

After 4 years of testing and several months waiting for the CNMNC to deliberate, Jaszczak’s team heard the news: Merelaniite was approved.

“I really wish that I had been given the opportunity to get in on the research,” said now 18-year-old Jessica Simonoff, because she was studying the original sample of tanzanite on which the merelaniite was first spotted, albeit for different purposes. These days, she’s a freshman in college, although she’s not quite sure what she’s going to study yet.

“I’m glad [the research] went somewhere and contributed to science,” she continued.

New Minerals Matter

“The occurrence of minerals teaches us what kinds of combinations of elements are possible,” Jaszczak said. Scientists can use what they learn from studying naturally occurring crystal structures and mineral properties to synthesize new materials.

“The occurrence of minerals teaches us what kinds of combinations of elements are possible.”

For now, merelaniite remains just a new mineral. One that like all minerals, “provides new insights into the way elements fit together in geologic systems,” Burns said.

“Whether this specific mineral would find an application in the future, who knows,” he continued. “It’s new knowledge that adds to the [scientific] understanding of how our planet works.”

—JoAnna Wendel (@JoAnnaScience), Staff Writer

Citation:

Wendel, J. (2016), Whiskers on familiar crystal revealed as new mineral, Eos, 97, https://doi.org/10.1029/2016EO062749. Published on 09 November 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.