The bridge between the museum community and the Earth science education and research communities has fallen into disrepair. Tight budgets limit the efforts of Earth science curators to create compelling displays and education programs for the public, and irreplaceable collections of rocks and minerals are in danger of being sold off or discarded. Rebuilding the connections has important benefits for everyone concerned.

In the past, mineral museums played an important role in documenting, preserving, and promoting geological diversity. For example, my employer, the North Carolina State Museum (now the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences), was founded in 1879 to attract attention to natural resources and to rebuild a crippled economy in the wake of the American Civil War. The state geologist’s collection served as the nucleus of the exhibits, which traveled as far as Paris, New Orleans, and the 1906 Centennial Exposition in St. Louis, Mo.

Museum collections are also an important source of research specimens: I have used mineral specimens from the Mineralogical and Geological Museum at Harvard University and the Smithsonian Institution in my own research. Collections are official repositories for type specimens for minerals and meteorites.

A third function of museum mineral collections is to educate visiting students, from K–12 up to the university level. Mineral exhibits benefit local economies by attracting tourists and mineral enthusiasts, who also gain an educational benefit.

Museums can’t perform these functions unless their mineral and rock collections are adequately funded and maintained. Geological collections have not had access to the types of funding typically available to other disciplines. For instance, the biological sciences recognize the value of long-term specimen storage, and money is available to support that. Some biology grants are even open to paleontology collections.

Even biological collections are not immune to funding cuts, however. This March, the National Science Foundation announced that it was not accepting new grant proposals for its Collections in Support of Biological Research program, which has been suspended indefinitely. An opinion piece on the nation’s beleaguered natural history museums and their collections ran in the Sunday Review section of the New York Times in early April. Geological curators can sympathize with the plight of the biological collections, but rock and mineral collections have been coping with this lack of funding as a matter of course for many years.

History for Sale

The urgency in supporting museum collections is predicated on an essential difference between geoscience collections and biological collections. Geology collections are worth money. Even the ugliest rock is “pedigreed” in a collector’s eyes. The parts of biological collections that could be monetized are species covered by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which forbids trade in endangered species. Paleontology collections have some monetary value, but the big money generally lies in sales of carnivorous dinosaur bones. However, Bureau of Land Management policy forbids sale of fossils found on public lands.

Administrators can get rid of a geology collection, free up space and budget, and earn extra money doing it.

In contrast, administrators looking to monetize collections can get rid of a geology collection, free up space and budget, and earn extra money doing it. The Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences (now the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University) took this step in 2006. Without external funding for collections support, I expect it will become more common in the future.

This issue took on a disturbing urgency for me when I found item 143B-135.233 in the 2015 North Carolina State Budget. This item specifically authorized the museum to sell or trade anything from its collections “when it is in the best interests of the Museum to do so.”

Scrambling for Public Funds

My role as geology research curator is to curate a unique natural resource used to generate new knowledge and understanding. The Geology Collection is a research collection, although we support exhibits as well. Our collection focuses on North Carolina’s geodiversity and, to a lesser extent, that of the southeastern United States. It contains many significant North Carolina specimens, most from sites that are now inaccessible. Many gold mines are now flooded, roadcuts have been landscaped, and urbanization has erased mines and outcrops alike. According to an account from one of my colleagues, the type locality for websterite, in Webster, N.C., has been dynamited and sold.

This collection serves as a seldom-used archive for the specimens collected by retiring professors, and we are tasked to preserve their life’s work in perpetuity. Support from the state of North Carolina is minimal, and we receive no funds for developing the collection, improving storage cases, or generating modern-day characterizations of specimens. We receive no financial support from any other sources.

Grant money is available from the National Geological and Geophysical Data Preservation Program, but these funds are offered exclusively to state geological surveys through the U.S. Geological Survey. Other grants apply only to the large repositories. Smaller collections and museum-based repositories have no access to these sources of funding.

The worst, and most flagrant, example of exclusion is the often-cited 2002 National Research Council report Geoscience Data and Collections: Natural Resources in Peril. A committee made up of paleontologists and petroleum exploration geologists generated the report, with no geology museum professionals included. Accordingly, museum-based mineralogy/petrology collections rated a total of two paragraphs in the entire 101-page report. Funding followed proportionally.

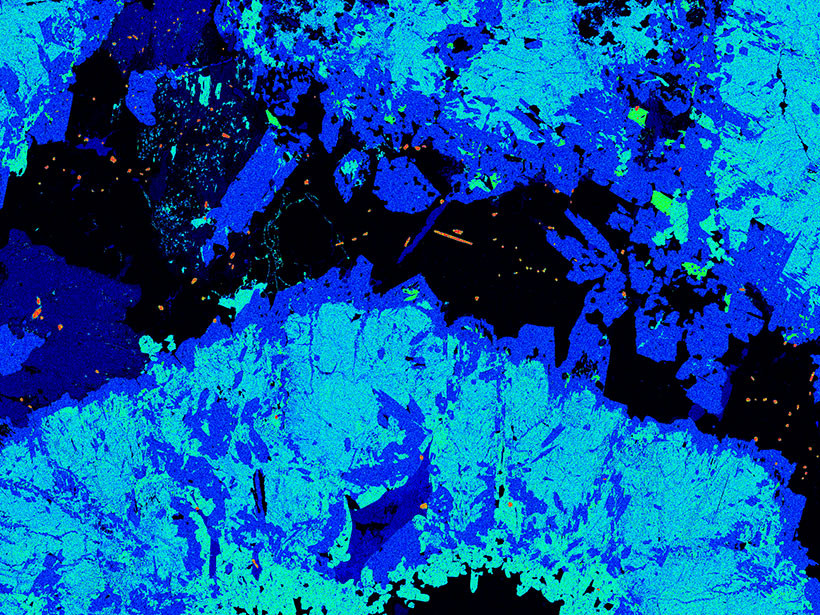

The only program on the horizon is National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded EarthCube, focused on creating digital infrastructure. If one digs deeply enough into EarthCube-funded iSamples, one can find mention of museums and actual physical samples. EarthCube represents a bonanza for computer professionals, but little or nothing for medium-sized museum collections where collection numbers are actually put on rocks. We need money for cases, database upgrades, trained assistants, thin sections, and analytical instrument time for validating mineral identification. We need money to address the special needs of curating radioactive minerals, asbestiform minerals, and sulfide minerals. But the money is going to digitization, so any funding for the long-neglected collections looks to be too little and too late.

Missed Opportunities

Museums are the open entrance to the pipeline, where children can begin to dream about a career.

If we look at the bridge from the other end, what do museums do to advance the profession of geology? Museums are the open entrance to the pipeline, where children can begin to dream about a career. It could be so for the geosciences too, but mineral museum exhibit design stagnated in the 18th century with the “cabinet of specimens.” Geology exhibits are generally limited to cases crammed full of minerals. Explanatory text is limited to a card with the mineral name and, sometimes, a chemical formula. This exhibit style has little value—educational or inspirational. A visitor can walk away from a case full of meteorites with the message that the museum owns a lot of little black rocks with funny names.

Few exhibits highlight the huge amounts of information represented by the minerals or the (nearly magical) ways in which we get that information by microanalysis and experiment. Recent findings in cosmochemistry, seismology, deep-sea drilling, volcanology, the deep Earth, and climate change are nearly totally absent.

Geoscientists own the best stories in all of the sciences, but these stories have all been appropriated by other sciences. Would we understand the depth and breadth of global warming as fully without stratigraphy, micropaleontology, and stable isotopes? Would organic evolution be as firmly established as the basis of biology without the proof that comes from the geosciences?

Museums and curators must follow the money, much of which comes from wealthy collectors. So mineral museum professionals gather at Tucson or Denver gem and mineral shows rather than American Geophysical Union or Geological Society of America meetings. The NSF Division of Earth Sciences does not fund the development of exhibits as a means of outreach. Informal science education grants allow exhibit design and development but only as one of a myriad of eligible formats. We are left with static mineral exhibits, which are cheap to build and maintain and are preferred by collectors. These fail to hold the interest of the casual visitors or of tech-savvy youth.

Looking Ahead

The research and academic communities should rethink their support of museums as repositories and archives. When a researcher retires and his or her samples end up in the dumpster, research is squandered. Funding a few major repositories may create an archive, but repositories lack the outreach and built-in audience a museum commands. Repositories completely lack an exhibits staff of professional writers, artists, and fabricators dedicated to reaching an audience.

The National Science Foundation is the principal support for the Earth sciences and is responsive to the needs of the community. Changes that extend funding to museum collections and outreach (from a finite budget) can be accomplished with the support of the community, within and outside of NSF.

The future of the Earth sciences depends on reestablishing mutually beneficial relations, rebuilding the bridge, between Earth scientists and Earth science museums. Museums need Earth science community support for funding for collections, exhibits, and programs that go beyond dinosaurs or ultraviolet fluorescent minerals. Museums must better support the scientists as direct outlets for information. Museums and geoscientists both need the next generation of geoscientists, who could discover all the wonders of geology at their local museum.

This essay represents the opinion of the writer, not the Museum of Natural Sciences, the Department of Cultural and Natural Resources, or the state of North Carolina.

—Christopher Tacker, Geology Unit/Research and Collections, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh; email: [email protected]

Citation: Tacker, C. (2016), The broken bridge between geology and museums, Eos, 97, doi:10.1029/2016EO051707. Published on 6 May 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.