Does it ever feel like there’s something missing from your work that you can’t quite put your finger on—something to bring more meaning and accessibility to your science? That missing element might be art.

Art and science have enjoyed a symbiotic relationship throughout human history. Over the past 2 centuries, Western society began perceiving these disciplines as more exclusive than complementary. But recently, rejection of this artificial separation has spurred a movement to recognize and revive mutually beneficial art-science collaborations.

Dovetailing Through Time

The superficial notion that art engages in expression while science engages in reason fed the split between art and science. In reality, the pursuits of each are more complex, and the overlap between the two is more substantial. Both scientists and artists are engaged in deeply observing and interpreting the universe.

Sculptor Sara Black, a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, describes humans as more than Homo sapiens—as “this other being, Homo aestheticus, [aiming] to understand the world around us and one another through metaphor and analogy.” Her perspective echoes that of Albert Einstein (a musician in his own right), who wrote in Living Philosophies that “the most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.”

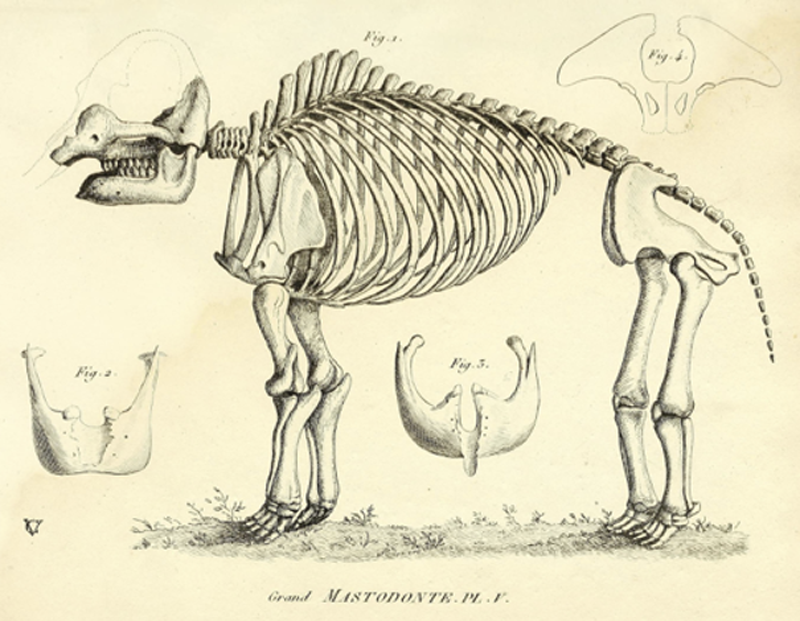

This mystery, and the synergy of art and science, was evident in the first known drawing of an American mastodon skeleton, created by French naturalist Georges Cuvier and published in Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes in 1821 (38 years before publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species). On the basis of fossil bones found in the Ohio River Valley, Cuvier imagined through his sketching a long-vanished species and introduced a new concept—extinction—that would change the field of biology forever. Cuvier was the first person to establish extinctions as a fact that any future scientific theory of life would have to explain.

Together, art and science communicate in ways neither can achieve alone.

Cuvier’s drawings represent just one example of the myriad ways that art and science have dovetailed over centuries. Together, art and science communicate in ways neither can achieve alone, and integrating art and science in research, engagement, and education efforts can expand the impact of any program or project.

Paul and Scott Slovic note in Numbers and Nerves that “anything that happens on a large scale seems to require that we use numbers to describe it, and yet numbers are precisely the mode of discourse that…leaves audiences numb and messages devoid of meaning.” And naturalist Aldo Leopold, in his 1949 book A Sand County Almanac, claimed, “We can only be ethical in relation to something we see, understand, feel, love, or otherwise have faith in.” For many, numbers are not enough to achieve this relationship. Enter: art.

Art can make scientific research and ideas accessible more broadly across society. It arouses emotions, illuminates connection to the world, and inspires action. Society ultimately benefits from art-science integrations as new ideas and approaches are increasingly seen as more engaging, hopeful, and relevant.

Finding Common Ground

In recent years, the arts have expanded in spaces where scientists network and exchange knowledge. Conferences have convened sessions exploring examples of synergies of art and music with science. Scientific publishing platforms are embracing papers and commentaries on art in the lives of scientists. Science museums and research institutions are showcasing art galleries—such as the Canadian Space Agency’s Satellite Art Gallery—to inspire scientific curiosity and advance scientific literacy. And that’s just a sliver.

The idea of synthesizing art and science is attracting a larger audience as more scientists pursue interdisciplinary approaches to research and communication.

Globally, the idea of synthesizing art and science is attracting a larger audience as more scientists pursue interdisciplinary approaches to research and communication. The depth of this growing interest was on display, for example, during AGU’s Fall Meeting in December 2022, where interdisciplinary work was presented in on-site and virtual exhibits, a community poem elicited contributions from more than 100 conference participants from 13 countries, and an “Art and Science” plenary session attracted a large audience.

The plenary convened practicing artists and scientists, who shared views of and experiences with working across the art-science interface. Dr. Mika Tosca, a climate scientist at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, described how art reaches us emotionally in ways that numbers cannot. She also highlighted how a solarpunk art ethos can help ground our response to climate change in joy and optimism, instead of fear and despair. (Solarpunk is an art movement that broadly envisions how the future might look if we lived in harmony with nature in a sustainable and egalitarian world.)

Sculptor Sara Black noted the false narratives “that scientists use one part of their brain and artists use another” and that “scientists need to do the serious work, get the information, then artists have to translate that to the public.” She countered that “to become whole beings, we need both perspectives.” She emphasized that artists and scientists have a responsibility to engage in “radical collaborations” that aren’t just “a cool thing to do” but are essential in solving urgent challenges of our times, such as climate change.

Baudouin Saintyves, a physicist, artist, and musician at the University of Chicago, described how he is “interested in questions first” and is “driven by aesthetics—something very common to both communities.” He noted that artists and scientists both “love fancy tools” and “pushing their techniques.” They often begin having fruitful conversations, he said, when they talk about these tools and methods.

Kimberly Blaeser, an Anishinaabe poet, photographer, and professor emerita at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, emphasized the similar “journey of inquiry” for both fields, “where you run into questions you had not expected, or contradictions.” Blaeser, an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation of Minnesota, also described art and science in Indigenous cultures, noting how rituals pair ceremonial aspects like dance and song with environmental practices. The traditional harvest of wild rice, for example, includes reseeding, narrative teachings, and performative ceremonies that invite direct participation in both the art and science of sustainable natural food production. “Beauty can also teach us things,” she remarked, emphasizing the need for art to be both affective and effective: beautiful, but also “doing something in the world.”

The final two panelists shared their individual experiences with art supporting direct action. Terry Evans, a photographer who resides in Chicago and Salina, Kan., related how her photos illustrate human predicaments in the face of industrialization and serve a pivotal role in inspiring community members to organize. Kikù Hibino, a Chicago-based sound artist, described efforts by courageous Japanese electronic musicians to oppose construction of a nuclear processing plant in their childhood community and recounted how that inspired him to become an artist.

How to Synergize Science and Art

Art can build bridges to bring community members into conversations involving science, helping position them as knowledge holders and contributors.

There are several different modes of art-science collaboration. In science communication, or “SciComm,” artists are recruited to help interpret and communicate scientific findings or conclusions for broader audiences. “SciArt” uses elements of science as inspirational seeds or media for artistic expression. Here artists may seek out scientists for access to tools and data to extend their artistic practice. A third mode, “ArtScience,” involves artists and scientists working together in transdisciplinary ways to ask questions, design experiments, and formulate knowledge. This approach can expand perspectives and enable artists and scientists to step out of self-imposed disciplinary boundaries. As Baudouin Saintyves reflected during the Fall Meeting plenary, by “welcoming art in your process, you [the scientist] can make your questions evolve and also make your scientific work more connected to society.”

In each of these modes, art can build bridges to bring community members into conversations involving science, helping position them as knowledge holders and contributors. This process dissolves boundaries defining “who is the scientist” and enables equitable access and contributions to knowledge making.

There are many avenues for scientists and science organizations to collaborate actively with artists and integrate art and science deeper into scholarly work. Examples include artist residencies, community-building projects, joint publications, artivism (arts-driven activism), funding opportunities and grant programs, and different approaches to public engagement.

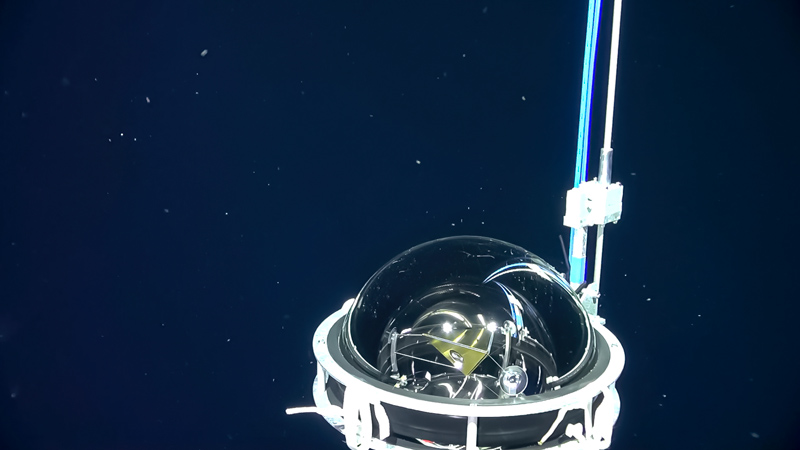

Artist residencies that invite artists to join scientific projects from their inception can be especially fruitful. In one example, a chance encounter on the winter ice of Lake Baikal in 2017 led to an ongoing collaboration between Canadian sound artist Jol Thoms and the Neutrino and Dark Matter Group (also known as SFB1258) at the Technical University of Munich. Thoms serves as an artistic inspirer and adviser, supervising engagement between physics students and art students.

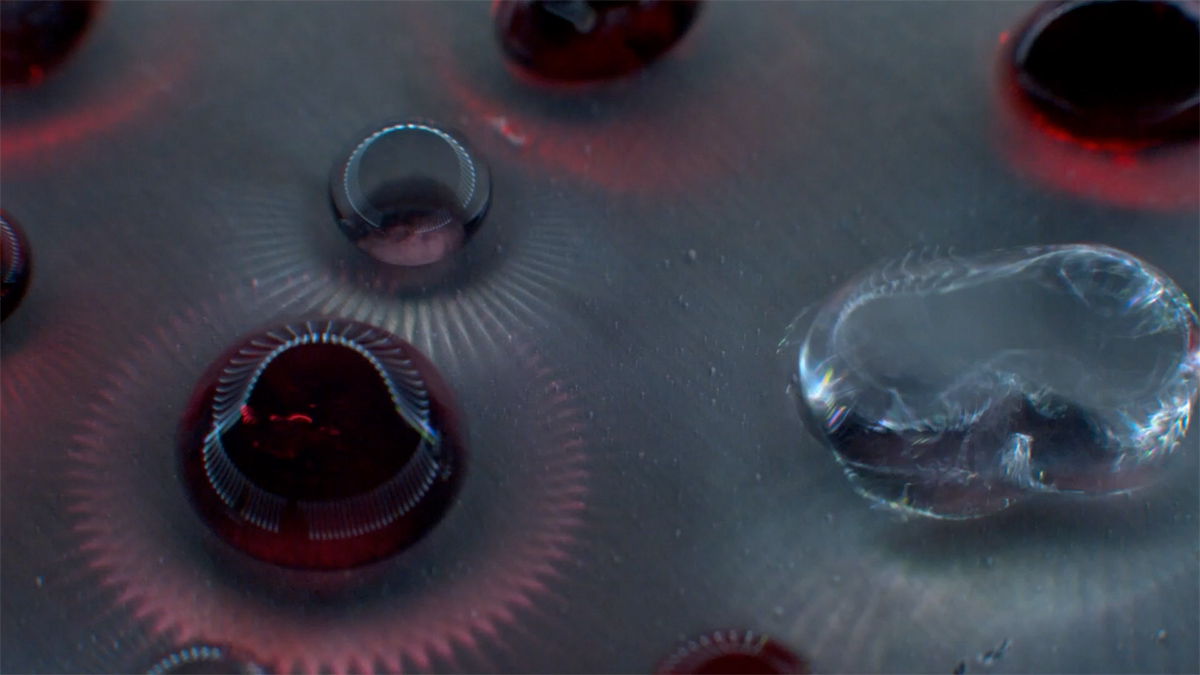

SFB1258, with Ocean Networks Canada, is also developing the Pacific Ocean Neutrino Experiment (P-ONE), which includes an ArtScience project that commissions compositions by musicians and sound artists. These compositions are transmitted in the deep ocean every full moon via a sound sculpture called Radio Amnion. Three other artists have also created and installed sculptures within some of the glass spheres that compose P-ONE test moorings.

Community and Collaboration

Community-building projects offer powerful opportunities for collaboration. The Nurture Nature Center in Easton, Pa., used a combination of science, art, and community to engage local youth, artists, municipal leaders, and residents in the co-creation of a vision for community resilience while also enhancing knowledge of weather and climate science, hazard risks, and strategies for hazard mitigation.

Through storytelling, forums, and other activities, participants collaborated with artists Jackie Lima, Don Wilson, and James Gloria to create large murals illustrating the community vision for three Pennsylvania communities. The murals highlight how art-science collaborations can help develop positive narratives about ideal futures and common goals to the benefit of public health and social cohesion.

Community-driven, science-informed art can also help communities heal after natural disasters by creating avenues for communication and connection and encouraging community members to gather and dialogue in public spaces.

Importantly, community building through art-science collaborations can leverage diverse knowledge sources, perspectives, and research priorities in the scientific process. For example, the Center for Limnology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison is creating space for youth artist mentees in its research projects via the Drawing Water program to “encourage the next generation to link art and science to generate a richer and wider value system.” Their projects incorporate participants from the sovereign tribal nations of Wisconsin and the Tribal Natural Resources Department of Lac du Flambeau.

In addition to diversifying perspectives, art and science can pave the way for historically marginalized communities to drive research questions and design solutions.

In addition to diversifying perspectives, art and science can pave the way for historically marginalized communities to drive research questions and design solutions. Recipients of the 2022 E(art)H CHICAGO grant, for example, showcased environmental challenges in Chicago by exploring intersections of art and environment. Projects ranged from the Filament Theatre bringing nature to youth in southeast Chicago through a forest-themed performance to art-making workshops along the Rio de Bienvenida/River of Welcome (i.e., the South Branch of the Chicago River) with artists Cynthia Weiss and Delilah Salgado.

Support for community-driven work through art-science synergy is also illustrated by the SmartICE project, which extends across Indigenous communities of the Canadian Arctic and centers on ice knowledge. One dimension of SmartICE’s work relies on Mittimatalik artist Jamesie Itulu’s illustrations to share intergenerational knowledge of ice travel and safety more widely. The project highlights the important role of art in mobilizing Indigenous science and community knowledge of climate and ice.

Synergies to Solutions

The synergy of art and science provides opportunities to explore solutions to “wicked problems” such as climate change. In 2013, oceanographer Gregory Johnson presented key ideas from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fifth Assessment Report through 19 haiku and watercolors, making the dense report accessible to a much larger global audience.

ArtScience residencies can also serve as tools for exploring solutions through a combination of activism, futuring, and policy advising. An example is the Tomorrow Is Already Here exhibition held at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito, Calif., in 2020. This exhibition summarized two thematic residencies that brought together artists, scientists, policymakers, and activists to consider solutions to climate change inequity via art making and imagination. Visual artist and Headlands Center program manager Aay Preston-Myint writes in the exhibition catalog, “The hope of this work is to produce a discourse which not only accepts climate change as truth (an unfortunately low bar), but to foster excitement, curiosity, and determination in facing its challenges, rather than fear and powerlessness.”

In When Words Fail, climate scientist Bill McKibben contends, “We haven’t come up with words big enough to communicate the magnitude of what we’re doing [to the climate].” Art can help bridge this gap.

Inspired yet? The above examples represent just the tip of the iceberg and help keep us open to the possibilities and connections that art and science can bring as we study, imagine, and actualize a better world. The urgent challenges of our time like climate change may seem insurmountable. However, Octavia Butler reminds us in her novel Parable of the Sower, “The world is full of painful stories. Sometimes it seems as though there aren’t any other kind and yet I found myself thinking how beautiful that glint of water was through the trees.”

Author Information

Kimberly Blaeser, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee; Dwight Owens, Ocean Networks Canada, Victoria, B.C.; Sarah Zhou Rosengard, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Ill.; Kathryn Semmens ([email protected]), Nurture Nature Center, Easton, Pa.; and Mika Tosca, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Ill.