Source: AGU Advances

More pocked with craters than any other object in our solar system, Jupiter’s outermost and second-biggest Galilean moon, Callisto, appears geologically unremarkable. In the 1990s, however, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft captured magnetic measurements near Callisto that suggested that its ice shell surface—much like that of Europa, another moon of Jupiter—may encase a salty, liquid water ocean.

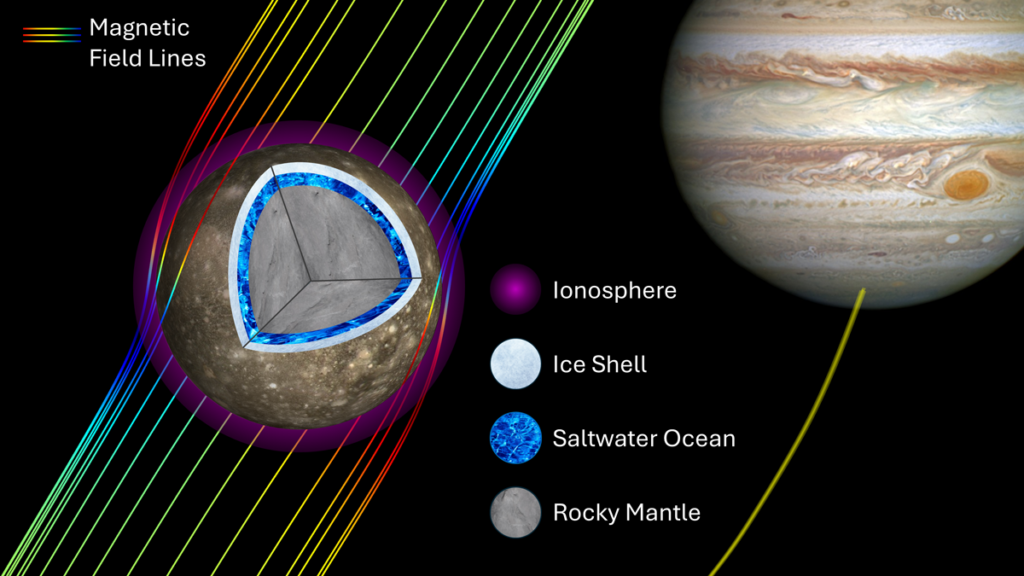

But evidence for Callisto’s subsurface ocean remained inconclusive, as the moon has an intense ionosphere. Scientists thought this electrically conductive upper part of the moon’s atmosphere might imitate the magnetic fingerprint of a salty, conductive ocean.

Now, Cochrane et al. have revisited the Galileo data in more detail. Unlike in prior studies, this team incorporated all available magnetic measurements from Galileo’s eight close flybys of Callisto. Their expanded analysis much more strongly suggests that Callisto hosts a subsurface ocean.

In addition to reanalyzing the flyby data with advanced statistical techniques, they used computational models of Callisto’s ionosphere and geophysical properties to examine whether a subsurface ocean is compatible with all available information.

They found that Callisto’s ionosphere alone cannot explain all existing observations, but that a subsurface ocean in combination with the ionosphere can. Further exploring which scenarios best fit the data, the researchers predicted that the ocean is likely at least tens of kilometers thick, as measured from the top of the liquid ocean to its seafloor, and encased beneath a solid ice shell that itself could range from tens to hundreds of kilometers thick. Beneath the probable ocean lies a rocky interior.

These findings set the stage for spacecraft measurements that will be captured in the near future and should confirm, once and for all, whether Callisto is an ocean world. Close-up measurements are scheduled for NASA’s Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency’s JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) missions, both already launched. China’s planned Tianwen-4 mission may also observe Callisto.

Confirmation of Callisto’s status as an ocean world would likely prompt further investigation on its potential to support life—just as the confirmation inspired research about Europa. (AGU Advances, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024AV001237, 2025)

—Sarah Stanley, Science Writer