An fascinating case study from the 24 June 2025 Granizal landslide in Medellín, Colombia, which killed 27 people and destroyed 50 homes, shows demonstrates that it is not just the urban poor that are exposed to landslides.

That urban areas can be subject to high levels of landslide risk is well-established – commonly cited examples are Hong Kong (which has a huge programme to manage the risk), Sao Paolo and Medellín, amongst other places. The well-established pattern is that it is the urban poor that have the highest levels of risk, being forced to live on slopes on the margins of the conurbation, often with poor planning and low levels of maintenance of, for example, drainage systems.

A fascinating open access paper (Ozturk et al. 2025) has just been published in the journal Landslides that suggests that this pattern might be beginning to change under the impacts of climate change. The paper examines the 24 June 2025 Granizal landslide in Medellín, Colombia, which killed 27 people and destroyed 50 houses. I wrote about this landslide at the time, including this image of the upper part of the landslide:-

The location of the headscarp of the Granizal landslide is [6.29587, -75.52722].

The analysis of Ozturk et al. (2025) shows that this is a 75,000 cubic metre failure with a source area length of 143 m and a width of 50 m. The landslide was triggered by rainfall over a 36 hour period.

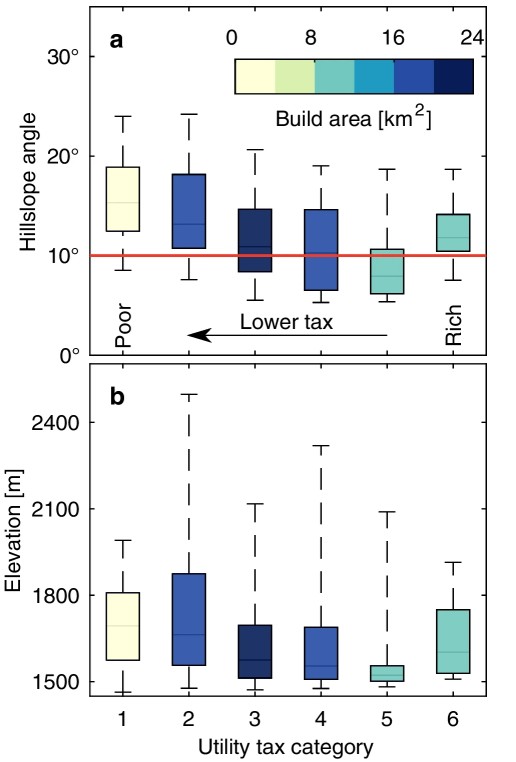

The authors’ analysis suggests that the landslide occurred on terrain that is steep even by the standards of Medellín, and at a comparably high elevation for the city. They have then looked at the distribution of income tax bands for the city according to both elevation and slope angle:-

The diagram shows that in Medellín, the poorest people live on the steepest slopes, and thus (at the first order) are more at risk of landslides. People with higher income levels tend to live on areas with a lower slope angle – the more affluent you are, the lower your landslide risk. However, this pattern reverses for those in the highest tax band (i.e. the richest). Those people live on steeper slopes (although not as steep as for the poorest people).

A similar pattern emerges for elevation, although the pattern is weaker. But compare Utility tax categories 5 and 6 for example – the richest people migrate to higher elevations.

This probably represents a desire by the most affluent to live in locations with the best views and in which they can have larger plots of land. A similar pattern is seen elsewhere – for example, property prices in The Peak in Hong Kong are very high.

It has been possible to live in these higher risk locations because of good identification of hazards for those that can afford it, the use of engineering approaches to mitigate the hazard and good maintenance of drains. These options are available to those with money, who live in “formal neighbourhoods” rather than unplanned communities. Of course, as Ozturk et al. (2025) remind us, the vulnerability of these communities is still much lower than that of the poor.

But Ozturk et al. (2025) make a really important point:-

“…we should not forget that climate change is gradually intensifying and may soon render the design criteria used for planning formal neighbourhoods obsolete. Hence, our concluding message is that future rainfall changes may also lead to catastrophic landslide impacts in formally planned urban neighbourhoods, challenging the assumption that only informal settlements are at high risk.”

The vulnerability of the poorest communities means that this is where the highest risk will continue to be located, and this is where the greatest levels of loss will occur. But our rapidly changing environment means that even more affluent communities are facing increasing levels of risk.

Reference

Ozturk, U., Braun, A., Gómez-Zapata, J.C. et al. 2025. Urban poor are the most endangered by socio-natural hazards, but not exclusively: the 2025 Granizal Landslide case. Landslides. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-025-02680-y