As rare landmasses dotting the vast Southern Ocean, South Africa’s Prince Edward Islands provide valuable insights for climatologists, geographers, biologists, botanists, and even astronomers.

The uninhabited islands act as natural laboratories for an array of research. For example, biologists study birds, marine mammals, plants, and microorganisms in an environment largely free from the impact of human activities. Even cosmologists and space scientists use the islands as a base from which to monitor solar activity and extraterrestrial radiation, areas of study with which radio and communication signals on the mainland can interfere, said Liezel Rudolph, a lecturer in geography at the University of the Free State in South Africa.

But despite their value to science, spatial data and associated metadata for the two islands (Marion and Prince Edward) were difficult to assess and validate. Rudolph and her colleagues quickly recognized the need to curate existing spatial data; when Rudolph herself began to work on Marion Island, she had to ask for spatial data from fellow researchers and mentors. “The one data type that all of the sciences on the Prince Edward Islands have as a common need is geospatial data,” she said.

Now, the Prince Edward Islands have a freely available, online geospatial database.

The Making of a New Database

Scientists from different generations and different disciplines working on the Prince Edward Islands (PEIs) left their marks on the maps—and those marks sometimes overlapped, Rudolph explained. “Many research groups use naming or coding conventions to identify experimental field plots or monitoring areas that are used year after year, and this information is sometimes captured in pencil on a map against the wall. Sometimes landmarks are used to identify these experimental plots, but these landmarks might not appear on a map—or might be marked as different features on different maps.”

To consolidate the geospatial information for transdisciplinary researchers and the public, Rudolph and her colleagues acquired a high-resolution digital surface model from South Africa’s directorate of National Geospatial Information (NGI) and used it as a baseline from which to create other data layers such as slope, aspect, and contours. Their study was published in the South African Journal of Science.

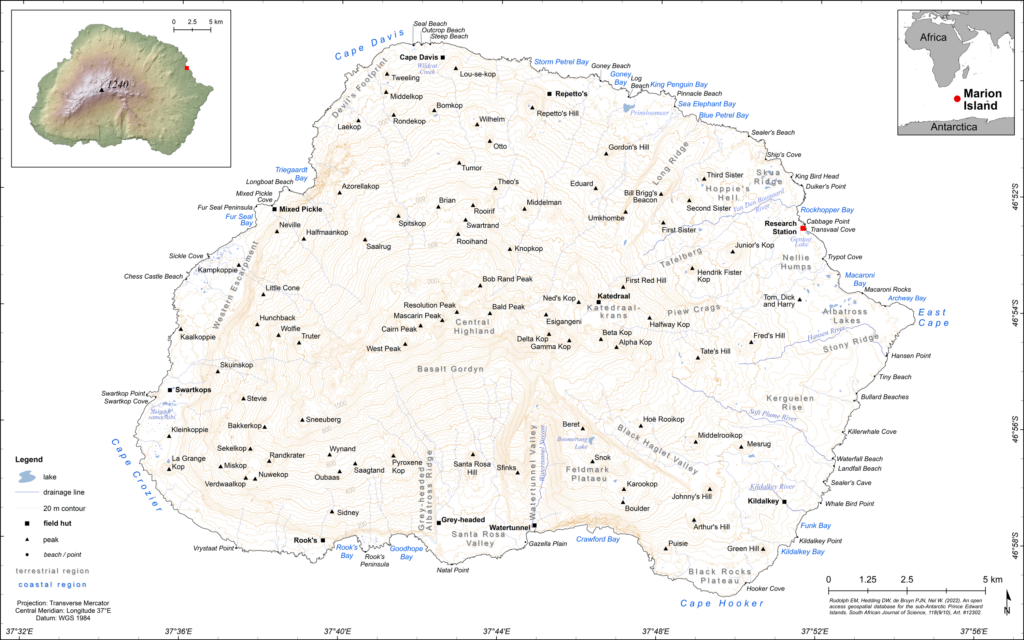

“We used [these] data and satellite imagery to map hydrological features such as lakes and drainage lines. Importantly, we also went through all the available literature documenting place-names, including gazetteers and the most recent maps published by the NGI and other national departments, to compile a comprehensive list of place-names. We cross-checked our list of place-names with experienced scientists from fields in geomorphology, biology, and ornithology who have spent many years working on the islands,” explained Rudolph.

When the researchers felt the list was as complete and accurate as possible, they matched it to the spatial data, digitally “pinning” place-names to features on the map, to provide accurate coordinates for each of the landmarks. These coordinates may be used for navigation (with handheld GPS) or mapping purposes in the future.

“I then used the place-name and spatial data to create maps that can be used for referencing as wall maps or in research work. It took around 6 months to create and compile the data set and another 3 months to check, clean, test, and validate it,” she said.

Rudolph and her team validated some of the data with ground observations, but most of the information in the new Prince Edward Islands database is based on remote sensing. This technique provides an accurate position (latitude and longitude) and elevation data with known error margins that can be accounted for when doing spatial analysis.

“Everything You Need Is There in Every Format You Can Think Of”

“The community of PEI researchers may be small, but this will be invaluable for all of us going forward.”

Janine Schoombie is a Ph.D. student at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, studying the effect of changing winds on the flight capabilities of grey-headed albatrosses breeding on Marion Island. She said having any open-source data is a dream for researchers. “The community of PEI researchers may be small, but this will be invaluable for all of us going forward,” she said.

“As someone continuing to do research on the PEIs, this database came at exactly the right time. I was busy writing a manuscript on my research and needed detailed GIS [geographic information system] data to make proper maps of my study site,” said Schoombie.

“I found it very useful and easy to use as they’ve packaged it,” she added. “Everything you need is there in every format you can think of. I didn’t have to spend a lot of time figuring out how to use the data on open-source GIS software either. This is a great example for me to follow when I need to publish data.”

Besides creating geographically accurate and detailed maps of study sites, Schoombie said researchers “will use these data to create solid 3D models of the two islands to improve fine-scale wind pattern simulations under different atmospheric conditions. This will provide valuable data for ecologists to understand the impact of wind on the terrestrial ecology of the islands.”

Rudolph hopes the database will provide a good starting point from which the general public can gauge the history and heritage of the islands. “If the islands had a ‘local community,’ it would be made up of the hundreds of scientists and field assistants who have spent the last 5 decades working there,” she explained. “And this contingent is a good representation of South Africa’s cultural and scientific diversity. The database provided here is compiled from names that are in use and widely accepted by this community.”

For now, Rudolph said if there is a need that the database doesn’t fulfill, it can be improved. But “at present,” she said, “we think we have addressed the most immediate needs of the Prince Edward Islands scientific community in terms of having an accessible spatial data set and a collated list of place-names.”

—Munyaradzi Makoni (@MunyaWaMakoni), Science Writer