Past and present human societies have deep connections to wetlands. The ancient Maya, a civilization that arose in Mesoamerica thousands of years ago, had extensive links to tropical wetlands, which they efficiently managed to mitigate drought and grow such crops as squash, maize, avocado, and other fruits.

“They found ways to engineer their environment to maximize their food production.”

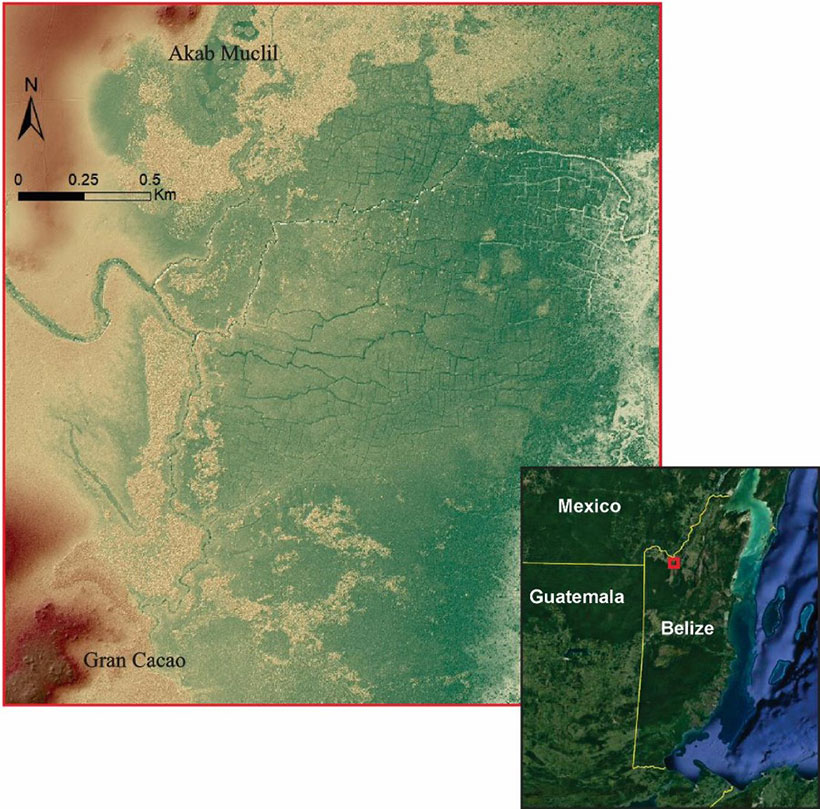

In a new study published in Anthropocene, Samantha Krause and her coauthors provide evidence that the Maya made large-scale changes to wetland ecosystems around their communities about 2,000 years ago. They began building canals and causeways to manage a complex agricultural system that likely fed the surrounding regions and provided resiliency during drought. These changes had a lasting impact on the landscape even today in what is now northwestern Belize.

“They found ways to engineer their environment to maximize their food production,” said Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach, a geographer at the University of Texas at Austin and co-author of the study.

Ancient Soil and Water Management

Luzzadder-Beach and her coauthors were interested in the ways the ancient Maya managed the soil and water of their environment to sustain their people while simultaneously coping with the local climate. Building upon their previous research that demonstrated extensive ancient Maya wetland agroecosystems, the authors used lidar scans and excavations at the Birds of Paradise wetland field complex. They discovered that the Maya had begun creating a system of canals to distribute water to crops and manage water chemistry starting about 2,100 years ago. By roughly the 5th century CE, they had built a causeway to give access to the various blocks of crops and help regulate water flow between them. Just 3 centuries later, the Maya were conducting more widespread land clearing and canal building.

“It’s very distinct in terms of how it was built and maintained,” Luzzadder-Beach said.

The authors were able to reveal that different blocks of farmland held crops like maize, cassava, avocado, medicinal plants, and fruits by conducting chemical analysis of pollen, charcoal, mollusk shells, and carbon isotopic ratios of soil. Timothy Beach, a geographer at the University of Texas at Austin and a coauthor on the study, added that these squares of crops in the Birds of Paradise wetlands also provided “protein traps” for edible mollusks like clams and mussels.

Elizabeth Paris, an assistant professor of archaeology at the University of Calgary who studies the Maya but was not involved in the recent research, said this chemical and soil analysis is teaching us how the ancient agricultural systems worked.

“It adds to our understanding about how elaborate [the Maya] could be in terms of managing the chemistry and the crops and different aspects of the ecology in a really fine-grained way,” Paris said.

Built to Last

Beach said the Birds of Paradise wetlands likely fell under the political control of Gran Cacao, an ancient city that reached its height during the Classic Period of Maya civilization. Gran Cacao isn’t well excavated because it is difficult to access, but it lasted roughly from 1000 BCE to 900 CE, around the time of the collapse of many Classic Maya cities because of factors like drought and political unrest.

The new study showed that the Birds of Paradise wetlands didn’t suffer a similar fate until a few hundred years later. Sediment accumulation in the canals and a changing ratio of pollen unearthed in the soil revealed that people continued to update and maintain this system until as late as roughly the mid-14th century, when natural forest pollen began to dominate soil deposits, the researchers found. The complex wetland management system may have allowed Maya communities to inhabit the area longer than other regional urban centers, the authors said.

“These fields allowed people to persist throughout that drought and stay in this region when other populations had declined around them.”

“These fields allowed people to persist throughout that drought and stay in this region when other populations had declined around them,” Beach said.

Paris echoed the surprise that the locals there continued to use this raised field system “despite political disruptions at the end of the late Classic Period.”

Although the canals may have fallen into disrepair, the landscape changes were so extensive that they remain today. Beach said that possibly because of the wetland’s engineering, the Birds of Paradise wetlands are more ecologically diverse than surrounding areas that weren’t as heavily managed by the Maya during ancient times. The wetlands attract larger animals like tapir and deer, and the local residents (including present-day Maya communities) still use them to harvest some of the same mollusks and fish that people in the region have been eating for 2 millennia.

“These are still lasting hydrological impacts,” Luzzadder-Beach said.

Paris said the study teaches us about some of the long-term impacts that humans can have on the landscape. “Those impacts can outlast the people who made them, by millennia in some cases.”

—Joshua Rapp Learn (@JoshuaLearn1), Science Writer

Citation:

Learn, J. R. (2021), Ancient Maya made widespread changes to wetland landscape, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO157922. Published on 05 May 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.