The outlook for our planet’s water future is anything but reassuring. Across much of the world, communities are already confronting prolonged drought, shrinking reservoirs, and the growing struggle to secure reliable access.

“Even without global warming, if water demand continues to rise steadily, scarcity is inevitable.”

Now, a new study in Nature Communications suggests that so-called day zero droughts (DZDs)—moments when water levels in reservoirs fall so low that water may no longer reach homes—could become common as early as this decade and the 2030s.

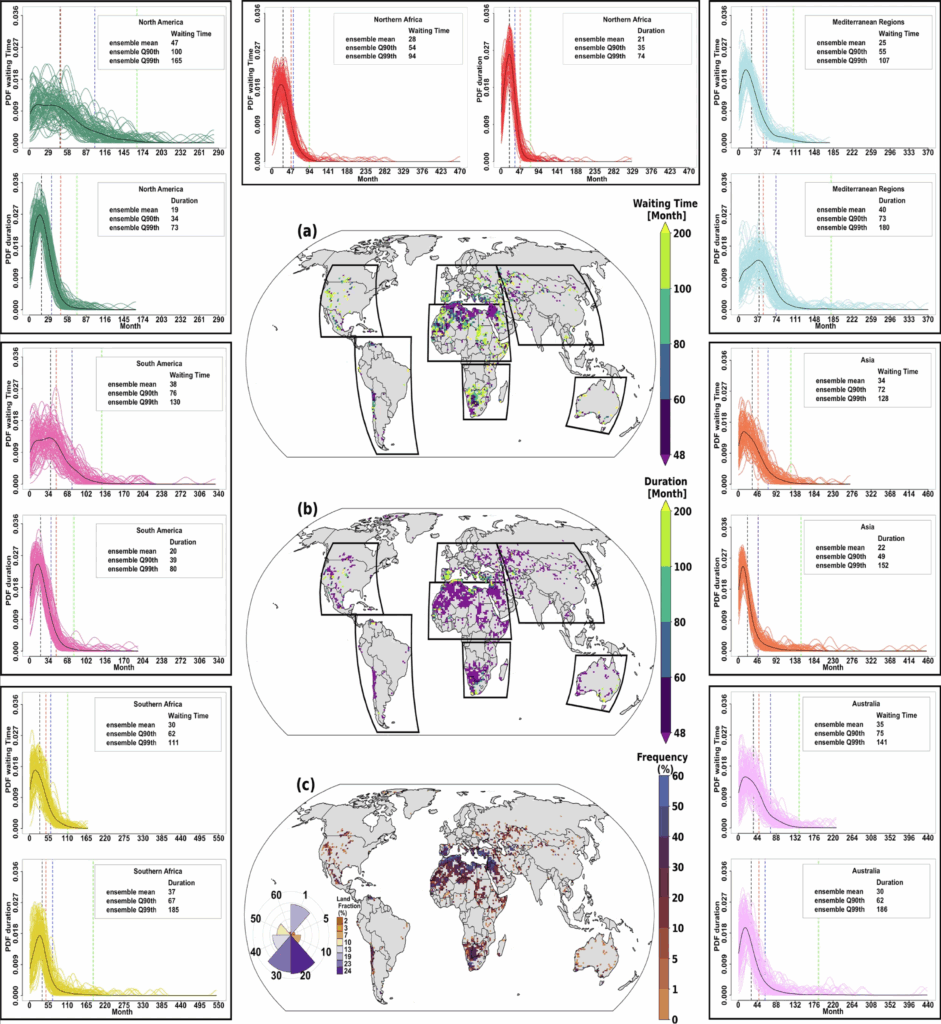

To find out where and when DZDs are most likely to occur, scientists at the Center for Climate Physics in Busan, South Korea, ran a series of large-scale climate simulations. They considered the imbalance between decreasing natural supply (such as years of below-average rainfall and depleted river flows) and increasing human demand (including surging economic and demographic growth).

“Most studies tend to focus on supply alone, not on the interplay between supply and demand,” explained Christian L. E. Franzke, a climate scientist and coauthor of the study. “But even without global warming, if water demand continues to rise steadily, scarcity is inevitable.”

Cities on the Edge of Thirst

The team found that urban areas face the highest risk of DZDs. As cities expand, their thirst for water often exceeds what local systems can provide, leaving them exposed to shortages and instability.

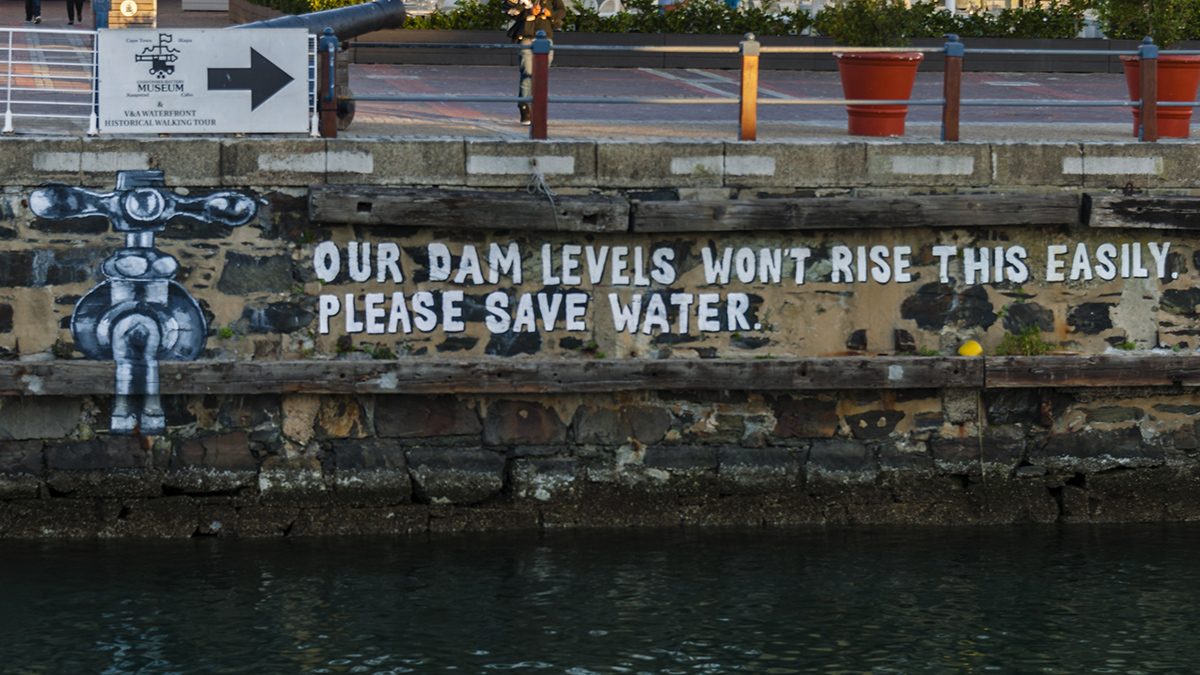

The near catastrophe in Cape Town in 2018, when water was rationed to avoid a complete shutdown, remains a stark warning for cities worldwide. “I remember the measures that had to be taken,” Franzke said. “There were severe restrictions—people had to limit their use to just a few liters a day.”

The human toll of DZDs goes beyond empty taps. It deepens existing inequalities, hitting low-income communities hardest because they are generally less able to endure rising costs of accessing clean water while also being more reliant on public utilities that are slower to secure alternate water sources. Urban DZDs also threaten public health by disrupting sanitation.

Overall, a DZD weakens economies and undermines social stability—especially in developing regions where physical, economic, and institutional vulnerabilities overlap.

According to the study, regions along the Mediterranean, southern Africa, and parts of North America are likely hot spots for DZDs, places where the zero point could arrive much sooner and last much longer.

“These already dry regions are becoming even drier,” said Alejandro Jaramillo Moreno, a hydroclimatology specialist from the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Jaramillo was not involved in the new study. “Global warming is amplifying the contrast between wet and dry areas. Where rainfall is scarce, it will likely become scarcer.”

Avoiding the Tipping Point

For Franzke, solutions must come not only from individuals using water more responsibly but also from policymakers who prioritize smart management and modern infrastructure. “There’s a lot of leakage,” he said. “Pipes are old, and water escapes before it reaches people. Updating this infrastructure is crucial.”

It may seem unthinkable that metropolises like Los Angeles could one day face evacuation because of water shortages, but experts warn that this scenario isn’t far-fetched if systemic solutions aren’t implemented.

In many regions, water rationing caused by severe drought is already a reality. Chile, for instance, has experienced a water crisis for more than a decade, and water is rationed in areas including the nation’s capital and largest city, Santiago. Iraq, Syria, and Turkey are experiencing one of the worst regional droughts in their modern histories.

Jaramillo takes a long view of civilizations’ relationship with water supply. “Throughout history, cities have reached their zero point—not only in water but in other essential resources,” he reflected. “The difference is that now, we still have time (and knowledge) to change course.”

—Mariana Mastache-Maldonado (@deerenoir.bsky.social), Science Writer