For more than one in 10 Americans, the Great Lakes are an important source of drinking water. The lakes also support a bustling maritime economy that includes a $7 billion fishing industry and $16 billion in recreation spending. But they’re also full of PFAS.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are toxic chemicals widely used in household products for their stain- and water-resistant properties. Exposure to some types of PFAS has been linked to certain types of cancer, immune system effects, developmental delays in children, and reproductive health problems. They’re known as “forever chemicals” because of their resistance to breaking down in the environment.

“This gives us an understanding of the extent of the contamination.”

PFAS can travel long distances in the atmosphere and groundwater and are remobilized via the water cycle. Because of their health and environmental effects, scientists are working to understand where PFAS come from and how they travel in the region. A new study published in Environmental Science and Technology reveals that precipitation is a major way PFAS enter all five of the Great Lakes.

“The Great Lakes Basin is one of our most important freshwater sources,” said Hayley Hung, an atmospheric chemist at Environment and Climate Change Canada who was not involved in the study. “This gives us an understanding of the extent of the contamination.”

Pouring PFAS

Researchers tested air, water, and precipitation samples at five sites, one at each of the Great Lakes, for 41 types of PFAS. Concentrations in the air samples correlated with population density, with the highest PFAS levels found in Cleveland and the lowest found at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore in northern Michigan.

PFAS in precipitation samples, though, were similar across the lakes. That’s because the types of PFAS that show up in precipitation tend to be those that easily evaporate and move long distances, becoming more evenly distributed in the atmosphere before they’re swept up by precipitation. “The sources are not local,” said Marta Venier, an environmental chemist at Indiana University and a coauthor of the study.

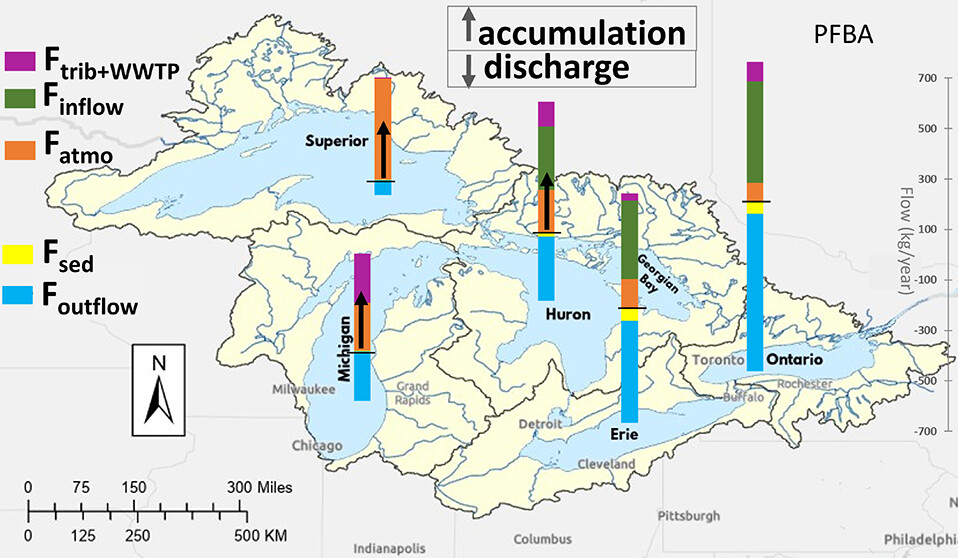

The team then combined their measurements with data on the lakes’ PFAS inputs and outputs from previous studies to determine how most of the chemicals were getting in. The answer, they found, depended on the lake—but precipitation had a large role to play.

For Lake Superior, precipitation was the greatest source of PFAS, whereas precipitation contributed about half of all PFAS in Lake Michigan. But the largest sources of PFAS changed alongside the flow of water. For example, the southeastern lakes—Lake Erie and Lake Ontario—get most of their PFAS from the inflow of water from other sources.

“If we don’t have these calculations, it’s not possible for us to implement mitigation.”

Researchers also found that Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Huron are accumulating PFAS, whereas Lake Erie and Lake Ontario are eliminating them. The Great Lakes expel PFAS either when the chemicals flow out to the ocean via the St. Lawrence River in southeastern Canada or when sediment particles bind to and trap PFAS in the lake beds, Venier said.

The new study gives the first complete picture of how PFAS are cycling through the Great Lakes, Hung said. Having that picture is the first step toward reducing contamination, she added. If researchers know how PFAS make their way into the Great Lakes, they can target those sources first to lower pollution. “If we don’t have these calculations, it’s not possible for us to implement mitigation,” she said.

The research underscores the importance of reducing PFAS from all sources, Venier said. “This reinforces the idea that tackling PFAS requires a multipronged approach.”

—Grace van Deelen (@GVD__), Staff Writer