For just under 20 years in the 10th century, the Khmer Empire was ruled from Koh Ker, once a major urban area in what is now Cambodia, now largely forgotten. During the majority of the Khmer Empire’s 600-year dominion in Southeast Asia, its capital was located not at Koh Ker but at Angkor, home to the largest temple complex in the world.

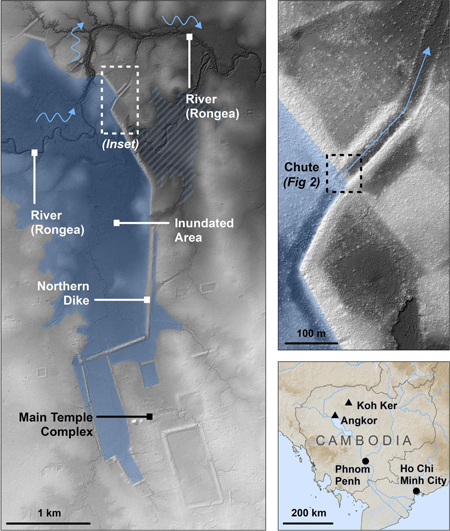

A new study has identified a culprit in Koh Ker’s short reign: its failed water management system. Using lidar, ground-penetrating radar (GPR), and hydraulic modeling, an international team of archaeologists led by Ian Moffat of Flinders University in Australia determined that the Koh Ker reservoir would have overflowed during its first or second rainy season.

“We can learn so much from studying water management infrastructure in ancient cities like Koh Ker,” said Sarah Klassen, an archaeologist with the University of British Columbia and coauthor of the study. “Many of the issues that the city dealt with in the past are the same as those faced by local inhabitants today.”

Renewed Interest in an Ancient City

Angkor’s long-term success was intimately linked to its complex water management network that sprawled over 1,000 square kilometers (620 square miles). This network, the most extensive of the preindustrial world, dramatically altered the landscape to divert water from the nearby Tonlé Sap lake.

“Water management networks do not build themselves, but rely on a complex set of social interactions on top of understanding landscape engineering and knowledge of the environment.”

“Studying water management is a basic part of understanding how cities function,” said Alison Carter, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Oregon who was not involved in the study. “Water management networks do not build themselves, but rely on a complex set of social interactions on top of understanding landscape engineering and knowledge of the environment.”

“Other than Angkor, Koh Ker was the only other site to become the capital of the Khmer Empire,” Klassen said. “This makes it an important site in terms of the politics of the empire but also in terms of our understanding of the nature of urbanism.” To understand Koh Ker’s failure, Klassen and her team decided to take a closer look at the reservoir that was constructed during the city’s brief time as capital.

Mapping a Buried Reservoir

The team focused their efforts on the reservoir’s northern spillway, following up on a 2018 study that mapped the southern spillway. Spillways are a common feature of reservoirs, meant to allow excess water to run out in a controlled manner.

They mapped the site’s surface using lidar, a technology that uses reflected light to create a topographical map. Because most of the spillway was underground, the team then excavated select sections and probed the length of the spillway using a metal rod to broadly understand its shape and depth.

Once they knew where to focus their efforts, they used GPR to reconstruct a picture of the parts of the spillway that remained underground. GPR uses a sensor dragged across the ground to measure the time it takes for electromagnetic pulses emitted into the ground to return to a sensor.

The GPR data were used to calculate the flow of water through the spillway chute when the water in the reservoir was at its highest point. The team then compared the amount of water the chute was capable of discharging, in combination with the norther chute, to the modeled rainfall in the area between 1980 and 2007.

They found that if the reservoir had been operating during those years, it would have overtopped at least once a year during every rainy season. The team concluded that the reservoir was prone to “catastrophic failure in the short term,” which would have undermined the authority of King Jayavarman IV, who was responsible for shifting the seat of power to Koh Ker, about 80 kilometers (50 miles) northeast of Angkor.

“The link that the researchers draw between state authority and successful water management opens the door for important questions concerning the nature and fragility of Angkorian rulership,” said Miriam Stark, an anthropologist at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa who was not involved in the study.

“I am impressed with the hydrological work that Moffat and his colleagues have completed at Koh Ker and would be delighted to see more work now on the people who lived and ruled there.”

The new study appeared in Geoarchaeology.

—Rachel Fritts ([email protected]; @rachel_fritts), Science Writer

9 February 2020: The name of the photographer has been corrected.

Citation:

Fritts, R. (2020), Poor water management implicated in failure of ancient Khmer capital, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO139666. Published on 03 February 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.