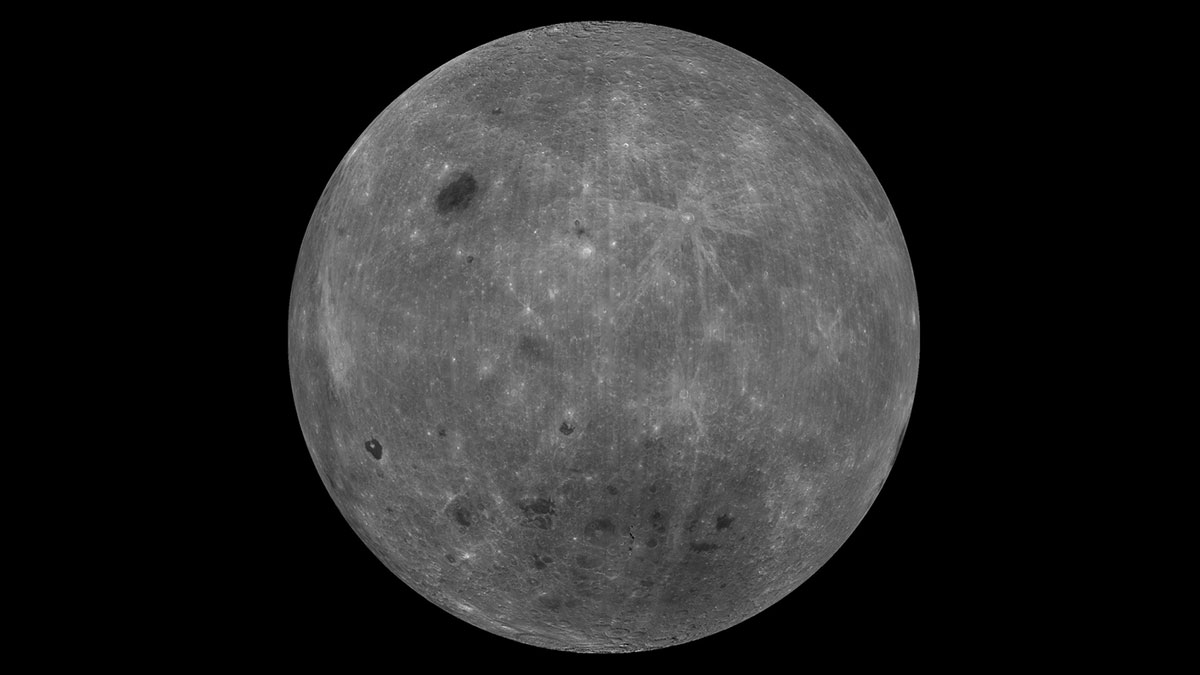

Until 1959, nobody on Earth had ever seen our Moon’s farside. Thanks to gravitational tidal forces, the lunar nearside always faces us, so it was surprising for everyone to learn that the other half of the Moon looks strikingly different. Not only that, but subsequent observations showed the lunar farside has a thicker surface than the nearside, and its rocks have different compositions.

And nobody knows exactly why.

However, some scientists think the solution to the mystery involves a site known as the South Pole–Aitken (SPA) basin, which was created by an asteroid impact early in the solar system’s history. A new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America draws from surface samples returned by the Chang’e-6 (pronounced CHAHNG-ua) robotic probe. The samples contain minuscule differences in chemical and isotopic composition that indicate the ancient impact may have vaporized part of the Moon’s interior, enough to account for the differences between the near- and farsides.

“Chang’e-6 currently provides the only samples returned from the lunar far side,” said planetary geochemist Heng-Ci Tian ( 田恒次) of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, in an email to Eos. Comparing these samples to those collected by previous Chang’e probes and the Apollo missions, Tian and his colleagues determined the impact did more than just make a big crater: It reshuffled the geological components of the lunar mantle. In particular, they looked at isotopes of moderately volatile substances such as potassium that vaporize at relatively low temperatures, rather than more abundant, low-mass elements like hydrogen and oxygen.

If this hypothesis holds up under further scrutiny, it would not only tell us about our Moon’s history and origins but help us understand planetary evolution in general.

As with Earth, the Moon’s mantle—the relatively plastic layer of minerals between the crust and core—is the source of the magma that once powered volcanoes. The nearside is marked by ancient volcanic flows, known as “mares” (pronounced MAR-ays) or “seas,” which are largely absent on the farside.

“Our study reveals that the SPA basin impact caused [evaporation] of moderately volatile elements in the lunar mantle,” Tian said. “The loss of these volatile elements likely suppressed magma generation and volcanic eruptions on the far side.”

If this hypothesis holds up under further scrutiny, it would not only tell us about our Moon’s history and origins but help us understand planetary evolution in general. After all, Earth’s surface is constantly renewed by plate tectonics and hydrologic processes, but other worlds such as Mars and Venus are less dynamic, and much of what is going on inside is still mysterious.

“There’s so many uncertainties as to really what happened [when SPA formed] and how it would’ve affected the interior,” said Kelsey Prissel, a planetary scientist at Purdue University in Indiana who was not involved in the study. She pointed out that different geophysical processes like crystallization and evaporation lead to different populations of isotopes. The new study, which shows a larger fraction of certain isotopes in the SPA region than on the lunar nearside, therefore provides strong evidence that the farside mantle was partially vaporized long ago.

“Previous studies have shown that impacts alter the composition and structure of the lunar surface and crust, but our study provides the first evidence that large impacts play an important role in planetary mantle evolution,” Tian said.

It Came from the Farside!

The SPA basin is one of the biggest impact craters in the solar system, so huge it doesn’t even look like a crater: It stretches all the way from the lunar South Pole to the Aitken crater (hence the name) at approximately 16°S latitude. Researchers determined it formed about 4.3 billion years ago—not long, in cosmic terms, after the Moon was born. Interestingly, it is also almost directly antipodal to a cluster of volcanoes on the lunar nearside, which suggested to some scientists the features might be related.

However, the farside is harder to study. Humanity’s first view came only in 1959 with the uncrewed Soviet Luna 3 orbiter, and none of the Apollo missions landed there. Robotic spacecraft have mapped the entire Moon in detail, but the Chang’e-4 probe achieved humanity’s first farside landing in 2019. Chang’e-6 landed in the SPA basin on 1 June 2024 and returned the first (and so far only) samples from the lunar farside to Earth on 25 June.

“[If] you looked at this data 20 years ago, [the samples] would all look the same.”

The next phase in the study was comparing the chemical makeup and isotopes in these rocks to their nearside counterparts collected by the Apollo astronauts and the Chang’e-5 mission. In particular, Tian and his colleagues looked at potassium (K), rare-earth elements, and phosphorous, collectively known as KREEP, which are possibly related to mantle composition. As the researchers noted in their paper, if the SPA impact vaporized materials in the Moon’s mantle, it might also have redistributed KREEP-rich minerals from the farside to the nearside. Testing this hypothesis required doing very sensitive laboratory measurements that weren’t possible in the Apollo era.

“Having the far side samples is brand-new no matter what,” Prissel said. “But looking at these really fine differences between isotopes is something we haven’t been able to do forever. [If] you looked at this data 20 years ago, [the samples] would all look the same.”

Prissel’s point highlights the interdependency of different branches of planetary science: Understanding the Moon’s interior requires studying samples, performing laboratory experiments on them (or on analog materials), and running theoretical models. These new results will inform the next set of experiments and modeling, as well as guide future lunar sample return missions.

“We plan to analyze additional volatile isotopes to verify our conclusions,” Tian said. “We will combine these with numerical modeling to further evaluate the global effects of the SPA impact.”

—Matthew R. Francis (@BowlerHatScience.org), Science Writer