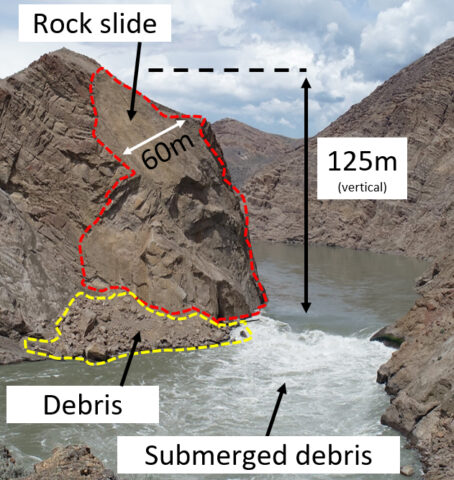

On 23 June 2019, Fisheries and Oceans Canada was alerted to a landslide that tipped 1,800 metric tons of rock into a narrow gorge in French Bar Canyon on the Fraser River in British Columbia, creating a 5-meter waterfall. Throughout the summer, rock-scaling crews dangled hundreds of meters above the river to remove hazards such as boulders the size of cars.

Salmon are famously strong swimmers, but this new barrier created a ticking time bomb for thousands of fish migrating from the ocean to spawning grounds upriver.

Wending its way more than 1,300 kilometers from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, the Fraser is a globally significant salmon-producing river. Critical to First Nations for food, social, and ceremonial needs, the five Pacific salmon species that breed in its tributary streams and lakes also support commercial and sport fisheries.

Salmon are famously strong swimmers, but this new barrier created a ticking time bomb for thousands of fish migrating from the ocean to spawning grounds upriver in late summer through autumn.

So a Unified Command incident management team was formed to resolve the emergency. It brought together geologists, biologists, engineers, and emergency personnel, plus leaders from British Columbia, the Canadian federal government, and First Nations.

Sam Fougère, senior engineering geologist with the consulting firm BGC Engineering Inc., attributed the landslide to fall rains followed by freezing and thawing, a process that loosened already fatigued, unstable rock.

For salmon swimming upstream, submerged debris from the landslide raised the river bottom, “like a speed bump,” said Northwest Hydraulic Consultants’ hydrologist Barry Chilibeck.

Visual observations and lidar monitoring informed slope housekeeping by the scaling crew. At river level, Fougère directed rock manipulation to create salmon passageways using airbags and hydraulic rams, rolling over giant boulders and moving small ones to make pools, then using hand drills, explosives, and expanding grout to break them. As the crew removed boulders, “fish almost instantly would find a path through,” he said.

Salmon began arriving in July, before channels were cleared, so the team began transporting fish upstream by helicopter.

Gord Sterritt, a member of the Gitxsan Nation, an executive member of the Fraser River Aboriginal Fisheries Secretariat, and executive director of the Upper Fraser Fisheries Conservation Alliance, quickly saw the issue’s importance for First Nations, particularly the 23 Nations originating or residing in areas of the river above the landslide. He joined the team’s joint executive steering committee to oversee operations like beach seining and a fish wheel to capture salmon. It was an interesting learning experience, said Sterritt, “and I’m grateful for it, though not for the landslide itself.”

Some 60,000 fish were transported by helicopter, with another 245,000 getting through manipulated rock channels, explained salmon biologist Scott Hinch of the University of British Columbia. Some fish were radio-tagged to follow their fates.

“Potentially Catastrophic” Barrier Remains

The helicoptering of fish was not as successful as scientists and engineers had hoped. Many of the fish captured and put in transport devices “had been milling about for some time, and there’s a lot of stress on these fish already at the barrier,” Hinch said. Capture and transport added more.

One of the stocks most profoundly affected was the endangered population of early Stuart sockeye, so named for their early migration. According to hydroacoustic detection, about 26,000 early Stuarts entered the Fraser. They arrived at the blockage before passageways were cleared, so “only 89 spawners got to spawning streams,” Hinch said. Many streams had no arriving spawners at all. And of another 177 early Stuarts transported to a fish hatchery, researchers could spawn eggs from only 17 mature females.

The 2020 salmon migration is fewer than 5 months away, and the barrier could be “potentially catastrophic.”

For now, salmon migration is over, but much of the blockage remains. The 2020 salmon migration, beginning with fish that migrate in spring, is fewer than 5 months away, and the barrier could be “potentially catastrophic,” said Hinch. The Canadian government is contracting out rock work over the winter.

Environmental scientist Jeremy Venditti of Simon Fraser University in British Columbia has been studying the geomorphology of the Fraser River since 2009. He has created an atlas of its 42 rock canyons, including French Bar. “What happens is, the canyon walls get undercut, and that removes the supporting rock underneath,” he explained. “Then everything on top slides into the canyon.”

Venditti’s 2019 survey at French Bar was canceled, as his boat operator was co-opted for the salmon rescue effort. But curious to pinpoint when the slide occurred, Venditti used satellite imagery to study the event, narrowing it down to 1 November 2018—meaning the remote landslide went undetected for nearly 8 months.

Given what’s at stake and the myriad of other stressors threatening salmon, is monitoring the river to predict and detect landslides a possibility?

Venditti thinks so. “This kind of thing is a routine occurrence in geological time,” he said, so “let’s try to predict where it might happen again.”

—Lesley Evans Ogden ([email protected]; @ljevanso), Science Writer

Citation:

Evans Ogden, L. (2020), Remote landslide puts Fraser River salmon on shaky ground, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO138786. Published on 22 January 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.