San Francisco, late 1970s. A lean, bearded man of about 60, casually dressed, gazes from a streetcar as it travels along Church Street.

Like any good guidebook author, he makes careful notes and the occasional sketch as he plans tours of the city, jotting down the most relevant details for future readers. Architectural highlights. Points of historical interest. Red, radiolarian-bearing chert interbedded with shale partings. The usual.

When Clyde Wahrhaftig accepted the Distinguished Career Award from the Geological Society of America (GSA) in 1989, the charismatic professor and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scientist recounted the genesis of what would become his beloved field guide to the geology of San Francisco.

A decade earlier, geophysicist and AGU president Allan Cox had mentioned that he was planning a fun run as a means of exercise for scientists attending AGU’s annual Fall Meeting. Wahrhaftig warned him off the idea, offering instead to encourage a gentler form of physical activity by way of a walking guide to geological outcrops around town. Cox was convinced, and Wahrhaftig spent the next 6 months crafting the guide in his spare time.

What Wahrhaftig achieved with the first edition of the work—thoroughly titled A Streetcar to Subduction and Other Plate Tectonic Trips by Public Transport in San Francisco—was a charming blend of local peculiarity and geologic spectacle that embodied the spirit and precision with which it was created. At AGU’s request, Wahrhaftig expanded the volume, and the 1984 edition remains one of his most enduring contributions to San Francisco geology and the field in general.

“It’s always been an inspiration to me,” said Christie Rowe, a Bay Area native who’s working with a team of fellow geologists to create a digital update of the guide called Streetcar2Subduction, set for a 35th-anniversary launch in time for AGU’s Fall Meeting in December. “It drove me to go out and figure things out for myself and helped me realize I could become a geologist.”

A Singular San Franciscan

“He was one of the best field geologists, I think, in the country, not only in terms of how he looked at the landscapes and the rocks but in how he encouraged his students to ask the right questions, explore the evidence in front of them, and do the science.”

Perhaps no one was more suited than Clyde Wahrhaftig to the task of leading geologic tourists around San Francisco via streetcar.

Born in Fresno, Calif., 100 years ago, Wahrhaftig studied geology at the California Institute of Technology and Harvard University, where he earned his Ph.D. A consummate field geologist with wide-ranging interests—including art, botany, music, and literature—Wahrhaftig was also an environmentalist who had been wary of cars and planes from a young age and used public transportation his entire life. Even when traveling to Alaska during his lifelong career with the USGS, Wahrhaftig opted to make the journey by boat.

He began teaching at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1960, and while he was, in his own words, a “lousy lecturer,” he excelled at teaching in the field. According to Doris Sloan, a retired professor of geology at Berkeley, “he was one of the best field geologists, I think, in the country, not only in terms of how he looked at the landscapes and the rocks but in how he encouraged his students to ask the right questions, explore the evidence in front of them, and do the science.”

Sloan first met Wahrhaftig in 1969, when she signed up for a summer extension course in geology. “To spend a week out in the glorious northern Sierra with this man was just an eye-opener,” she said. “At the end of the week, I thought if I could do anything in the world I wanted, I would become a geologist and lead trips like that. I was 39 or so at the time.”

Sloan went on to earn her Ph.D. in geology from Berkeley, where she had a 40-year career as a professor and a leader of geology field trips for alumni.

Wahrhaftig, she said, wasn’t initially enthusiastic about women in the field but soon reversed his stance, offering his support to Sloan and other women in the department.

“I owe my professional joy in geology to Clyde and only to Clyde,” said Sloan, now 89. “It’s thanks to Clyde that I had the life and career I did.”

In 1971, Wahrhaftig became the first chair of a new GSA committee, Minority Participation in the Earth Sciences. It was an issue he would remain involved with for the remainder of his career.

A Blueprint for the Future

“The things he was doing at the end of his life—when he realized it was important that he was open about his identity, his experiences—are sort of a blueprint for what I hope we [as a community] will continue to do in the future in terms of allowing people to feel comfortable sharing stories of who they are and how that impacted their journey into science.”

When Wahrhaftig gave his acceptance speech to GSA in 1989, he spoke at length about Cox, who had taken his own life 3 years earlier. “Receiving this award for longevity has made me realize that my time to do good is running out,” Wahrhaftig said, going on to disclose his homosexuality and the relationship the two men had shared.

In choosing to come out at that moment, Wahrhaftig hoped to reach gay students, their straight counterparts, and their academic leaders, imploring the last to recognize gay individuals’ contributions to the field.

Benjamin Keisling, who specializes in paleoclimatology and glaciology, stumbled on Wahrhaftig’s story after researching historical figures in the geosciences who were openly gay. Keisling received his Ph.D. from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and was an active supporter of Amherst’s chapter of Out in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (oSTEM).

“I was surprised that no one had ever told me about this, because it was such a powerful story for me,” Keisling said. “The things he was doing at the end of his life—when he realized it was important that he was open about his identity, his experiences—are sort of a blueprint for what I hope we [as a community] will continue to do in the future in terms of allowing people to feel comfortable sharing stories of who they are and how that impacted their journey into science.”

A member of AGU’s Diversity and Inclusion Advisory Committee, Keisling is set to give a presentation on Wahrhaftig at this year’s Fall Meeting. “As someone on this new committee…it’s been really powerful to read about…the strategies that Clyde and others at the time implemented to try to address [a] problem that is still really persistent,” he said.

Collaborating Across Time

In the 25 years since Wahrhaftig’s death, attitudes on diversity aren’t the only things that have changed in the field of geology. Today, technology allows geoscientists to apply tools like lidar and cosmogenic exposure dating to their work, and one geologist has used these to continue a glacial mapping project that Wahrhaftig began in Yosemite National Park in the 1950s.

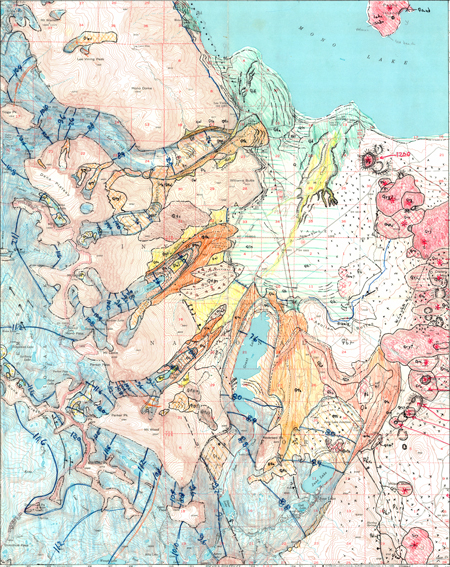

When Greg Stock became Yosemite’s first park geologist in 2006, Wahrhaftig’s family requested that he complete the late scientist’s decades-long mapping of the park’s glacial extent, using money Wahrhaftig had willed for that purpose. Stock agreed, and he and Wahrhaftig became, as he described it, “collaborators across time.”

Like Wahrhaftig, Stock found himself caught up in the project. “I came to understand at least one possible reason why Clyde never finished it, which is that it’s an absolute joy to spend time in the backcountry of Yosemite thinking about where glaciers used to be,” he said.

Ultimately, it took Stock 14 years to bring the project to its conclusion. Part of the funds from Wahrhaftig’s bequest will go toward printing copies of the finished work so it will be available for purchase at the park.

“From what I learned of Clyde, educating the next generation of geologists—especially a diverse group of geologists—was really important to him,” Stock said. “He was in science because he was curious about the natural world, he cared deeply about the natural world, and he wanted to inspire people to feel the same way.”

A Streetcar for the Digital Age

Rowe, coeditor of the Streetcar2Subduction update, explains that the digital interface she and other team members developed will be experienced via a new creation tool in the Google Earth app. This interface will allow Wahrhaftig’s walking tours to be undertaken virtually, an option the team hopes will be particularly handy for classrooms.

“Geology is under our feet everywhere,” Rowe said, “but without a bit of information to get you started, it’s hard to find a way in.”

To create the guide, Rowe and the team spent a little over a year virtually tracking down every site mentioned in Streetcar and making updates based on what changed in the 35 years since its publication. Some sites are no longer observable and may not be major points of interest on the virtual tour. The virtual aspect of the update did, however, allow the team to add sites that aren’t accessible by public transportation, which had excluded them from Wahrhaftig’s original version.

As users make each tour, either remotely or on the ground, they’ll have access to information in updated language, plus photos and video.

“Streetcar to Subduction is such an amazing resource, and it’s so wonderful that they’re re-creating it,” Keisling said. “You never know who’s going to [use it] and say, ‘Wow, not only is this an amazing resource, but this was written by a guy who did a really great thing and worked really hard for a long part of his career to make sure that geoscience wasn’t just accessible to white men, but…to as many people as wanted to participate.’”

According to Sloan, one of Wahrhaftig’s greatest legacies was “his ability to present geology in terms the intelligent lay person can understand—and to write in a way that made the field so exciting.”

—Korena Di Roma Howley ([email protected]), Science Writer

This article was edited to update information about the education of Doris Sloan and to correct the professional affiliation of Greg Stock.

Citation:

Howley, K. D. R. (2019), The layered legacy of Clyde Wahrhaftig, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO136549. Published on 06 December 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.