In classic literature, wetlands—ecosystems characterized by permanently or periodically water-saturated land—have too often been depicted as dangerous, gloomy, desolate places.

“Look at Tolkien and the Dead Marshes, look at some of Dickens or Austen,” said Christian Dunn, an environmental scientist at Bangor University in Wales. “The wetlands are where the ne’er-do-wells and villains hang out.”

“Wetlands are the superheroes of natural ecosystems when it comes to the power they have to help us combat the two biggest crises that we’re facing: climate breakdown and biodiversity loss.”

In reality, though, wetlands are not wastelands. They’re vibrant ecosystems, especially important in a changing climate. Wetlands are biodiversity hot spots and provide carbon sequestration. They also manage water—storing it quickly during heavy rain events and releasing it slowly during dry spells.

“Wetlands are the superheroes of natural ecosystems when it comes to the power they have to help us combat the two biggest crises that we’re facing: climate breakdown and biodiversity loss,” said Dunn.

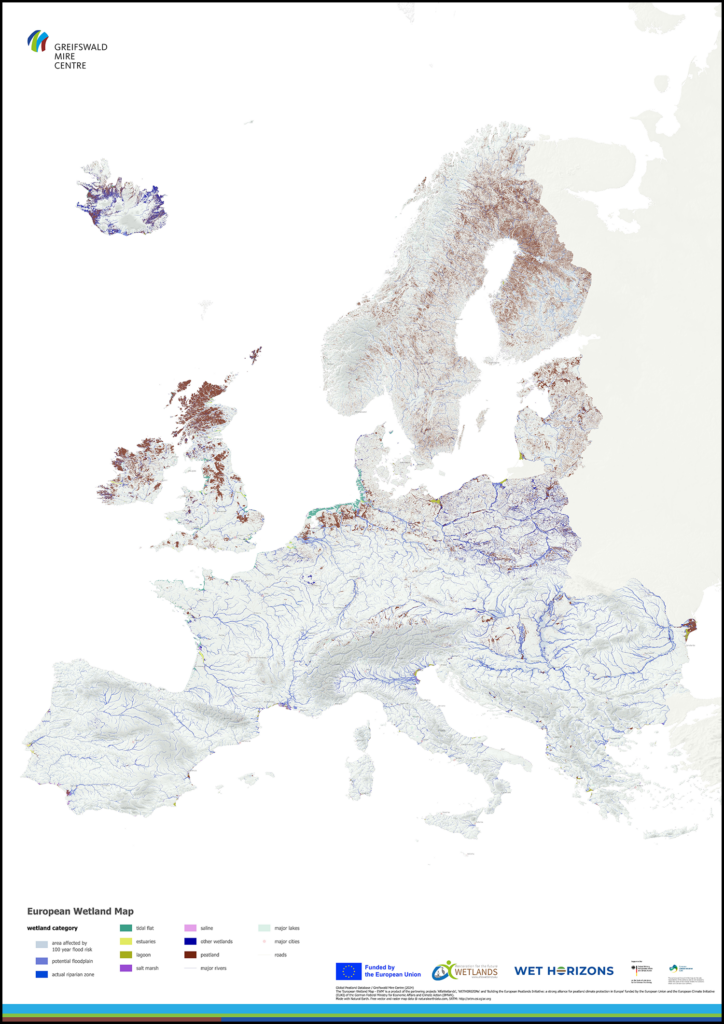

In the past 100 years, Europe has lost 80% of its wetlands, a diverse array of inland and coastal ecosystems that include peatlands, riparian zones, marshes, bogs, swamps, and floodplains. With much of this valuable ecological resource threatened in both the past and present by development and drought, knowing the locations of wetlands across the continent is important for preserving and protecting what exists today.

Mapping the Mire

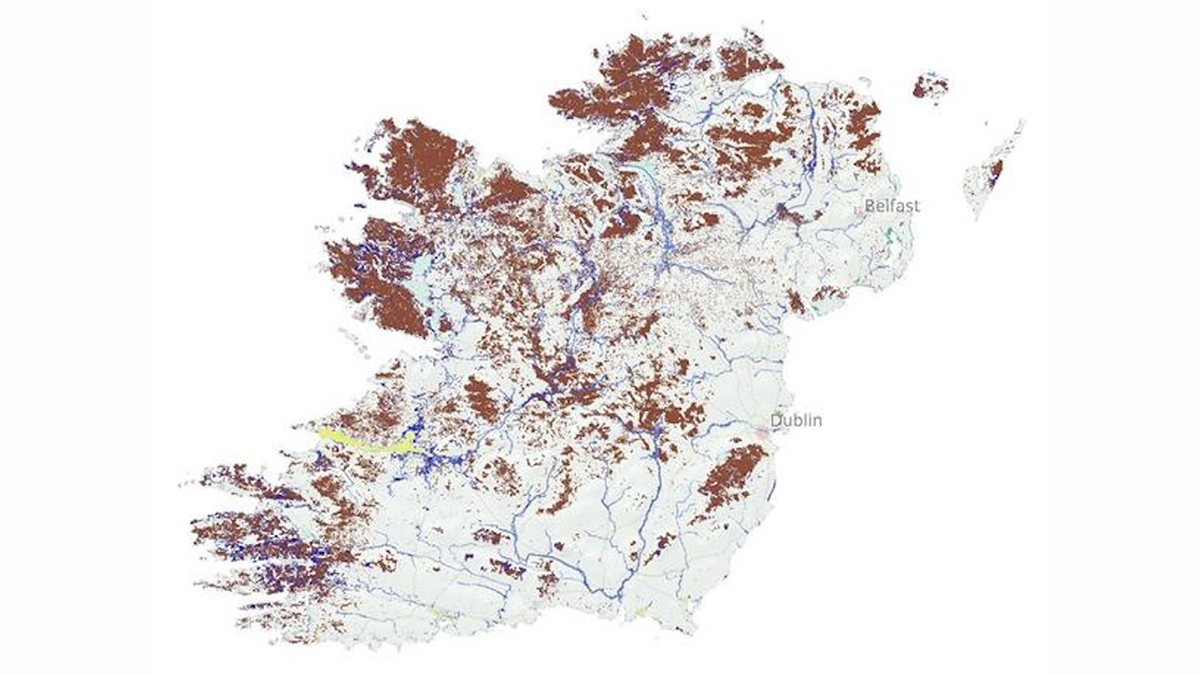

A new tool to help identify areas for conservation and restoration is the recently released European Wetland Map, which merges different types of geographic information system (GIS) data to create a comprehensive guide that can be used by researchers, developers, landowners, and residents to help protect Europe’s wetlands for the next 100 or more years.

Creating the new map required about 200 geospatial datasets identifying peatlands, floodplains, and coastal wetlands across most European countries through a mosaic of different resources—previously produced maps, satellite imagery, remote sensing, topographic wetness indices, and digital elevation models, as well as observational methods. The European Wetland Map is available for anyone to download—and there are datasets for each individual country included in the project.

Peatlands in particular are challenging to map with any one dataset, explained Alexandra Barthelmes, a senior scientist with the Greifswald Mire Centre and one of the map’s authors. “If people today talk about mapping, they have this top-down approach. They use satellite images and indices, mapping anything new.” Land use can hide or obscure some of these changing or critical areas, though, so researchers had to look back and incorporate Europe’s wetland history as well.

“I became aware of archives of soil and other mapping from the 20th century. It was a gold mine to bring this together and redraw and assess,” said Barthelmes.

The project also used previously published maps of floodplains and coastal wetlands. Several hundred years ago, for instance, agricultural use and river diversion drained the water in Hungary’s Pannonian Basin and dried out one of Europe’s largest wetlands. Maps from the 18th and 19th centuries detailed six different types of wetlands in this region, categorized by how military troops could traverse it.

“We forgot about how this landscape had been 100 years ago,” said Barthelmes.

Getting to Know Your Local Wetland

“We have it in our psyche that wetlands are unpleasant places to be. Nothing could be further from the truth. I hope the average person gets out, sees this map, and uses it to explore a wetland.”

Understanding flood risk is one crucial reason for policymakers and landowners to use the new map—there is a GIS layer that shows floodplains, helping home in on the locations prone to dangerous 100-year events, like the devastating floods that hit Spain last year.

Knowing more about local wetlands not only can inform where it may or may not be a good idea to build a house but also can help connect communities to the vibrant ecosystems present across all of Europe.

“We have it in our psyche that wetlands are unpleasant places to be. Nothing could be further from the truth. I hope the average person gets out, sees this map, and uses it to explore a wetland,” said Dunn.

—Rebecca Owen (@beccapox.bsky.social), Science Writer