Playing against Nature: Integrating Science and Economics to Mitigate Natural Hazards in an Uncertain World is an AGU textbook advocating an integrated approach to natural hazards where geoscience, engineering, economics, and policy perspectives are combined to develop risk mitigation strategies. AGU asked one of the book’s authors, Seth Stein, some questions about the book and what geoscientists and AGU members can contribute to natural hazard assessment and mitigation. Stein, currently the President of AGU’s Natural Hazards Section, coauthored the book with his late father, economist Jerome Stein.

What is the book’s major theme?

Defending society against natural hazards is a high-stakes game of chance against nature, involving tough decisions.

Defending society against natural hazards is a high-stakes game of chance against nature, involving tough decisions.

– How should a developing nation allocate its budget between building schools for towns without ones and making existing schools earthquake-resistant?

– Does it make more sense to build levees to protect against floods, or to prevent development in areas at risk?

– Would more lives be saved by making hospitals earthquake-resistant, or by using the funds for patient care?

Or what should scientists tell the public when—as occurred in L’Aquila, Italy, and Mammoth Lakes, California— there is a real but small risk of an upcoming earthquake or volcanic eruption?

Recent hurricanes, earthquakes, and tsunamis show that society often handles such choices poorly.

Recent hurricanes, earthquakes, and tsunamis show that society often handles such choices poorly.

Sometimes nature surprises us when an earthquake, hurricane, or flood is bigger or has greater effects than expected from detailed hazard assessments. In other cases, nature outsmarts us, doing great damage despite expensive mitigation measures or causing us to divert some of our limited resources to mitigate hazards that are overestimated.

Society can do better by combining geoscience with social science to analyze a problem and explore the costs and benefits of different options, in situations where the future is very uncertain.

Why is it essential to integrate a social science perspective into a scientific understanding of natural hazards and disasters?

Natural hazard mitigation involves “wicked” problems, which are tough societal challenges for which crucial information about what nature will do is missing, the best strategies to address the hazard are unclear, different interested groups have different goals, and proposed solutions involve complex interactions with other societal goals. Moreover, the consequences of the solution may yield undesirable repercussions that outweigh the intended advantages.

Communities need to combine the information that geoscience can provide with approaches from social science to formulate “sensible” approaches.

These contrast with “tame” problems in which necessary information is available and solutions, even if difficult and expensive, are straightforward to identify and execute.

Because there’s no “right” answer, communities need to combine the information that geoscience can provide with approaches from social science to formulate “sensible” approaches given their available resources and sociocultural factors.

How can scientists help decision makers do better to mitigate natural hazard risks?

We can show humility in the face of nature’s complexity, even as we learn more about it. There’s a tradition of speaking of “the” hazard as though it were known or knowable, in which case making policy choices would be straightforward. In reality, given our limited knowledge of how natural processes work and the complexity of these processes, much of what we’d like to know is poorly known or unknowable.

Despite our continuing best efforts as scientists, some of the uncertainties are unlikely to be reduced significantly on a short timescale. Hence, we should present both our knowledge and its limitations. We can explain what we know, what we don’t know, what we think, and which is which. Decision makers can factor these into their planning, just as they factor in political, economic, demographic, and other uncertainties.

It’s five years since your book was published. Since then, has anything changed regarding natural hazard incidence, risk, and mitigation?

The need to acknowledge and explore uncertainties is increasingly recognized.

The need to acknowledge and explore uncertainties is increasingly recognized, probably because some recent earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, storms, etc. have not been forecast well. Hence there’s a lot of effort going into assessing how well forecasts predict what actually happens and how to do better.

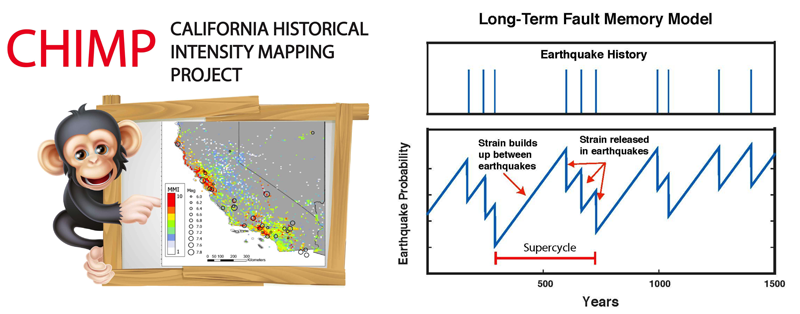

For example, I’m working with other researchers on assessing and improving earthquake hazard maps. We’re compiling a 160-year record of earthquake shaking in California, called CHIMP, that we will use to explore how well hazard maps forecast shaking.

We’re also developing new models in which faults have hot streaks—earthquake clusters—and slumps—earthquake gaps—just like sports teams, that will give new insight into the probability of future large earthquakes.

Other earthquake researchers (see Evans, 2017; Cattania, 2019; Crowell 2019; Morton 2019), and researchers studying floods (e.g. Quinn et al., 2018; Wing et al., 2018), landslides, hurricanes, tsunamis, volcanoes (e.g. Manga, 2018; Lowenstern et al., 2017), and other hazards, are exploring other issues related to forecasting. A lot of insight seems to be coming out of this.

Do you find that students are pessimistic about the incidence of natural disasters or optimistic about the role of science and technology in prediction and mitigation?

We’re lucky in that increasing numbers of bright and motivated students are interested in natural hazards. I see this among students working with me and across the whole geoscience community, both in the US and other counties. They’re interested in tackling fundamental scientific problems and using the results to help do a better job of mitigating hazards. This book, which I’ve used in classes in Germany and the United States, is designed to help them by both presenting information and by outlining some areas where there’s lots to do, so they can make important contributions.

How can AGU help promote natural hazards research and mitigation?

Historically, different hazards have been treated separately, but we increasingly realize that issues in forecasting, uncertainty, and mitigation have many elements common to different hazards.

As President of the Natural Hazards Section, I’ve been thinking a lot about this. Our section’s goal is to help people working on different hazards discuss topics of common interest.

Historically, different hazards have been treated separately, but we increasingly realize that issues in forecasting, uncertainty, and mitigation have many elements common to different hazards.

This hit me at a session on flood forecasting. One speaker illustrated the idea of underestimated uncertainties using a slide of the history of measurements of the speed of light, and another discussed the tradeoff between using funds for schools or for flood prevention. I realized that I use the same slide and say almost exactly the same things in my talks about earthquakes.

Many things are being done as part of the AGU Centennial, including special sessions at the Fall Meeting and a project in which graduate students interviewed people who experienced some California earthquakes to learn about the intensity of shaking that occurred.

The Natural Hazards Section is also developing programs for early career and student members including field trips, a YouTube channel, and events to help younger members discuss career options with established natural hazards scientists from a range of disciplines and sectors including academia, government, and industry. Efforts like these will grow in years to come.

Playing against Nature: Integrating Science and Economics to Mitigate Natural Hazards in an Uncertain World, 2014, ISBN: 978-1-118-62080-9, list price, $75.75 (print), $60.99 (e-book)

—Seth A. Stein ([email protected]), President, AGU Natural Hazards Section, and Northwestern University, USA

Citation:

Stein, S. (2019), Society’s high stakes game of chance against nature, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO136109. Published on 29 October 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.