Source: Geophysical Research Letters

Variations in the Earth’s space environment can disturb our planet’s geomagnetic field, inducing electric fields in the conducting crust, mantle, and oceans. If space weather is stormy, these geoelectric fields can drive uncontrolled current power grids sufficient to cause blackouts and even wreak permanent damage.

It has happened in the past, and we can expect it to happen again in the future—an extremely intense magnetic storm could cause continental-scale failure of electric power grids. Such an event would have long-lasting negative consequences on society.

New research by Love et al. provides some clues on what might happen to electric grids during a large geomagnetic storm. The work is part of the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) contributions to an interagency project called Space Weather Operations, Research, and Mitigation (SWORM), initiated by the White House’s National Science and Technology Council in 2015.

Specifically, the researchers created maps of geoelectric fields that estimate what would be generated by a magnetic superstorm. The researchers used two kinds of data to create the new maps.

First, they used monitoring data collected at magnetic observatories operated by the USGS and in other countries within the International Real-time Magnetic Observatory Network (INTERMAGNET) consortium. From these data, the team constructed a latitude-dependent statistical function of geomagnetic activity. Second, they used magnetotelluric survey data acquired by the National Science Foundation’s EarthScope program and a smaller set of data collected by the USGS. These data measure the relationship between induced geoelectric fields and the inducing geomagnetic field at different locations across the continental United States.

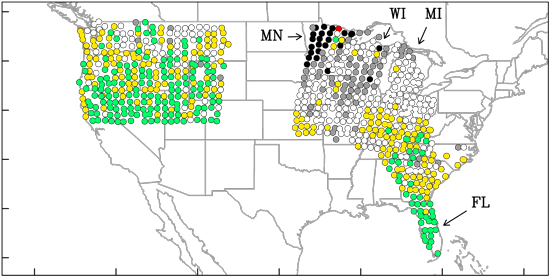

By putting those two sets of data together, the researchers were able to create a hazard map, showing the strength of induced geoelectric fields during strong magnetic storms—storms with strengths that are only likely to occur once per century. They found that the strength of these fields can depend significantly on location—by more than 2 orders of magnitude. The authors also found that Minnesota and Wisconsin have some of the highest areas of geoelectric hazard, whereas Florida has some of the lowest.

Magnetotelluric data are not yet available for the whole United States, so a country-wide assessment is not yet possible. However, the authors expect that dense power networks in the northeast, which has complicated underground structures, would experience large hazards from induced geoelectric fields.

A disruption of electrical power could be disastrous in highly populated metropolitan centers, so predicting possible geoelectric hazards across the rest of the United States is an important ongoing project. (Geophysical Research Letters, doi:10.1002/2016GL070469, 2016)

—Leah Crane, Freelance Writer

Citation:

Crane, L. (2016), Mapping geoelectric hazards across the United States, Eos, 97, https://doi.org/10.1029/2016EO060683. Published on 13 October 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.