Source: Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth

As part of the earthquake cycle, most active faults suddenly release strain that has gradually accumulated for extended periods of time. Some faults, however, may experience aseismic slip, or creep, which sometimes begins after a major seismic event and then steadily declines over time. Determining the relative proportion of seismic and aseismic slip occurring along an active fault is critical for accurately estimating its potential seismic hazard.

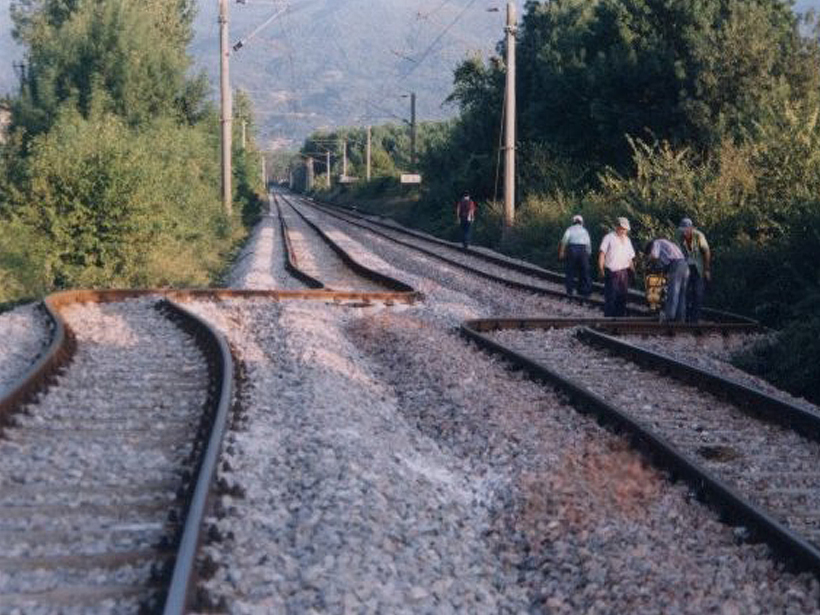

In a new study, Aslan et al. used recent, high-resolution interferometric synthetic aperture radar data to characterize aseismic slip occurring along Turkey’s North Anatolian Fault, the 1,600-kilometer-long strike-slip feature separating the Eurasian and Arabian plates that has produced seven large (magnitude > 7) earthquakes since 1939. The most recent event, the 1999 magnitude 7.4 Izmit earthquake that occurred roughly 100 kilometers east of Istanbul, ruptured five segments and killed more than 20,000 people.

Using 307 images acquired by the Sentinel-1 and TerraSAR-X satellites, the researchers examined ground velocity changes in space and time across the central segment of the 1999 rupture for the period spanning 2011 to 2017. The results indicate this segment continues to creep nearly 2 decades after the earthquake but that its maximum rate in the fault-parallel horizontal direction has tapered to an average of roughly 8 millimeters per year, about two thirds the rate measured during the previous decade.

The team also presented evidence for a transient “creep burst” that occurred along the same fault segment in November 2016. During this spike, the surface slip totaled 10 millimeters—a distance that corresponds to 1.25 years of average creep—in just 3 weeks.

Collectively, these findings indicate that postseismic slip along the North Anatolian Fault is more complex than has previously been suggested. By providing evidence that creep is not necessarily a steady process, this study offers new insight into long-term, postseismic deformation following a major earthquake along one of Earth’s most active strike-slip faults. (Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JB017022, 2019)

—Terri Cook, Freelance Writer

Citation:

Cook, T. (2019), Variations in creep along one of Earth’s most active faults, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO124931. Published on 06 June 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.