Source: Global Biogeochemical Cycles

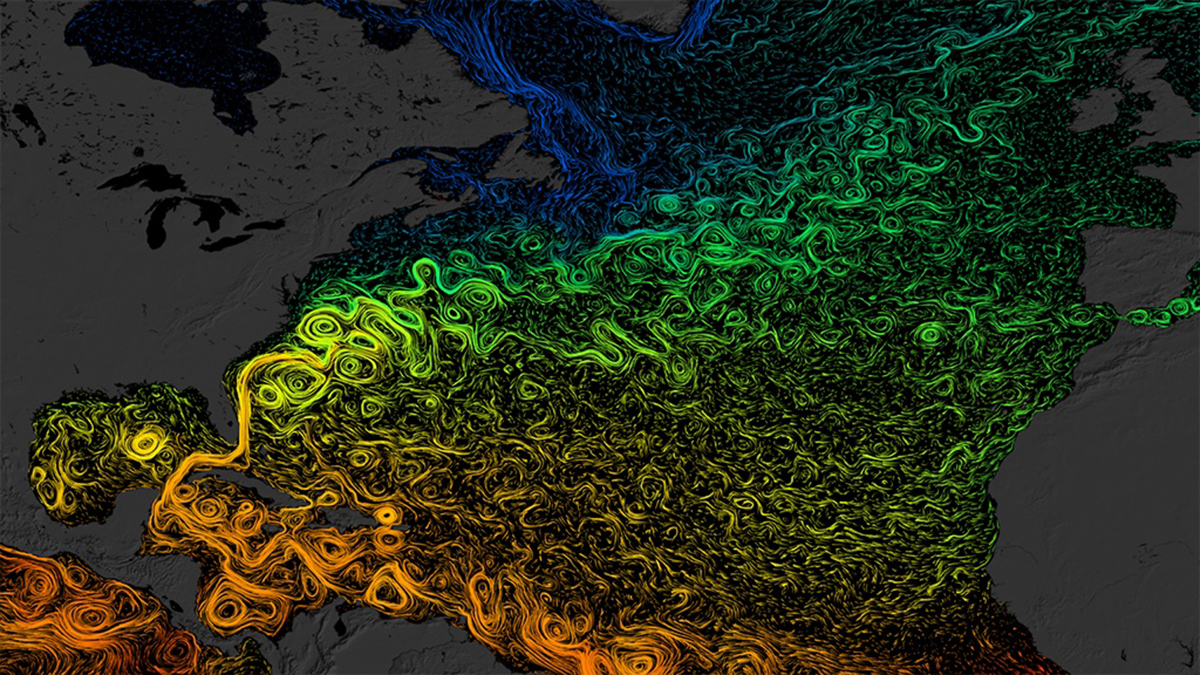

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is the system of currents responsible for shuttling warm water northward and colder, denser water to the south. This “conveyor belt” process helps redistribute heat, nutrients, and carbon around the planet.

During the last ice age, occurring from about 120,000 to 11,500 years ago, millennial-scale disruptions to AMOC correlated with shifts in temperature, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), and carbon cycling in the ocean—as well as changes in the signatures of carbon isotopes in both the atmosphere and the ocean. At the end of the last ice age, a mass melting of glaciers caused an influx of cold meltwater to flood the northern Atlantic, which may have caused AMOC to weaken or collapse entirely.

Today, as the climate warms, AMOC may be weakening again. However, the links between AMOC, carbon levels, and isotopic variations are still not yet well understood. New modeling efforts in a pair of studies by Schmittner and Schmittner and Boling simulate an AMOC collapse to learn how ocean carbon storage, isotopic signatures, and carbon cycling could change during this process.

Both studies used the Oregon State University version of the University of Victoria climate model (OSU-UVic) to simulate carbon sources and transformations in the ocean and atmosphere under glacial and preindustrial states. Then, the researchers applied a new method to the simulation that breaks down the results more precisely. It separates dissolved inorganic carbon isotopes into preformed versus regenerated components. In addition, it distinguishes isotopic changes that come from physical sources, such as ocean circulation and temperature, from those stemming from biological sources, such as plankton photosynthesis.

Results from both model simulations suggest that an AMOC collapse would redistribute carbon throughout the oceans, as well as in the atmosphere and on land.

In the first study, for the first several hundred years of the model simulation, atmospheric carbon isotopes increased. Around year 500, they dropped sharply, with ocean processes driving the initial rise and land carbon controlling the decline. The decline is especially prominent in the North Atlantic in both glacial and preindustrial scenarios and is driven by remineralized organic matter and preformed carbon isotopes. In the Pacific, Indian, and Southern Oceans, there was a small increase in carbon isotopes.

In the second study, model output showed dissolved inorganic carbon increasing then decreasing, causing the inverse changes in atmospheric CO2. In the first thousand years of the model simulation, this increase in dissolved inorganic carbon can be partially explained by the accumulation of respired carbon in the Atlantic. The subsequent drop until year 4,000 is primarily driven by a decrease in preformed carbon in other ocean basins. (Global Biogeochemical Cycles, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GB008527 and https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GB008526, 2025).

—Rebecca Owen (@beccapox.bsky.social), Science Writer