The volumes and varieties of data coming from all types of scientific instrumentation around the globe and beyond are rapidly growing. Appropriate curation and management of these data enable scientists to share and access them efficiently and to reuse and capitalize on them effectively.

Many scientists intuit that research data management (RDM) done well does not mean using dusty USB drives or aging laptops for storage. Yet the path to strong data management is not always clear. How is RDM done? Who does it? Bolstering cyberinfrastructure and human capacity to ensure that the data being collected are reusable by both humans and machines can help advance science.

Skills for RDM, which involves organizing, documenting, analyzing, preserving, and publishing data, are increasingly important for scientists today. These skills allow scientists to keep up with trends in data acquisition and complexity, as well as the opportunities and efficiencies afforded by advanced computing power and global information exchange.

Effective RDM underpins interdisciplinary scientific research by providing mechanisms for consistent sharing and translation of information across fields. For example, the 10-year, $500-million Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative investigated impacts of oil, dispersed oil, and dispersants on Gulf ecosystems following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. Effective data management planning and use of established metadata standards resulted in successful stewardship of more than 3,000 datasets, representing more than 150 terabytes of data generated by more than 3,000 people. The resulting 1,700 scientific publications crossed multiple disciplines, including biology, oceanography, engineering, socioeconomics, and human health.

Instruction on research data management (RDM) has not been integrated widely into curricula, and science students are rarely taught data management as part of their formal education.

Powerful examples like this help explain why strategies for data management and sharing are increasingly required in scientific grant applications. For example, the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, among many other federal agencies, require applicants to include a data management plan in their proposals that lays out how data will be stored, curated, maintained, and shared. These requirements, developed partially in response to shifting public sentiment, as well as guidance to U.S. agencies from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, have trickled down to the wider scientific community.

Despite such requirements, instruction on RDM has not been integrated widely into curricula, and science students are rarely taught data management as part of their formal education [Strasser and Hampton, 2012; Aikat et al., 2017; Demchenko and Stoy, 2021]. As a result, students may enter the professional world ill-equipped to handle the data management requirements of contemporary science.

Students have reported frustration at this lack of instruction, and at times they have taken it upon themselves to learn data management skills and share knowledge with peers [Roberts-Pierel et al., 2021]. This individual approach is one option, but community-wide and systemic solutions may be a more efficient way to build a scientific workforce well-versed in RDM.

Many scientists worldwide have expressed increasing urgency to address a looming RDM skills gap in the geosciences workforce specifically, including community members in the Earth Science Information Partners (ESIP), an organization of data professionals and data scientists from government agencies, academia, and industry [Schuster et al., 2019; Donaldson and Koepke, 2022].

To respond to these concerns and plant seeds for action, we hosted a session at the ESIP Meeting July 2023 that drew dozens of participants from this community. The session engaged attendees in developing potential actions for individuals and programs to take to help close the gap in data management education at undergraduate and graduate levels.

Finding Fertile Ground

The ESIP community has been working for years to improve access to data management training for early-career researchers [Hoebelheinrich and Hou, 2016]. ESIP maintains a Data Management Training Clearinghouse that supports openly available training materials and multiple modes of delivering these trainings. Further, many of the data professionals involved work at research data repositories or institutional data archives and have firsthand experience building bridges and interfaces between researchers and such organizations [Bishop et al., 2021, 2023]. We ourselves have experience helping scientists contribute data to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, the Ocean Biodiversity Information System, the CLIVAR and Carbon Hydrographic Data Office, and other repositories.

Our experiences and ideas about integrating RDM further into higher science education seem to resonate with individuals serving in a wide range of roles in the Earth science and life science communities.

Outside ESIP, projects like the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission’s OceanTeacher Global Academy (OTGA) are working toward similar objectives within the framework of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). OTGA offers courses covering various facets of RDM in support of SDG target 14.A, which aims to “develop research capacity.” However, the efforts and advances of ESIP and other groups appear not to have reached teaching paradigms in the broader academic communities of domain sciences.

As we have shared our experiences and ideas about integrating RDM further into higher science education with colleagues, our discussion seems to resonate with individuals serving in a wide range of roles in the Earth science and life science communities—from field, bench, and dry lab science to scientific society leadership. This resonance, which motivated our ESIP meeting session, highlights a need in the scientific community to advance such integration by acting across the spectrum from individuals to institutions.

From Seeds to Saplings

The session began with opening provocations from several speakers that provided a wide range of examples of formal and informal opportunities to learn about RDM and that primed participants to think about the topic from various perspectives (e.g., the data manager, the teacher, small versus large institutions).

Participant breakout groups then discussed the question, “If there were no resource limits or other restrictions, what concrete actions would you take to ensure undergraduate and graduate students graduated with the necessary data management skills?” Each group then submitted its top actions to a collaborative document, and we ranked the results as a full group.

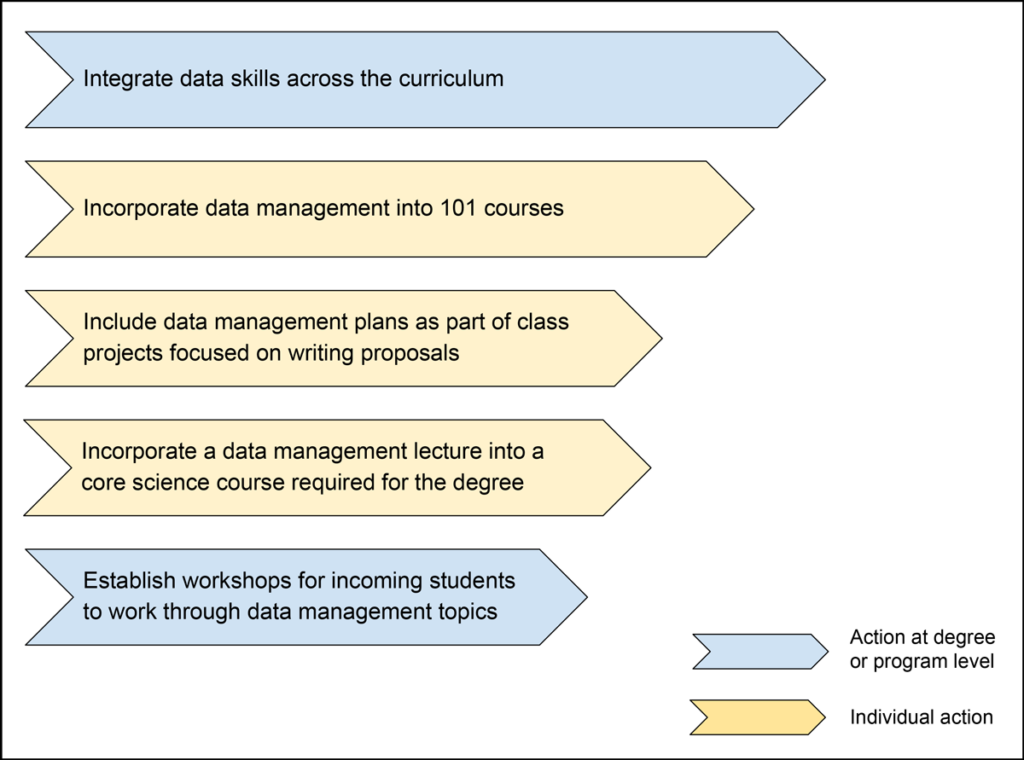

The top five potential actions identified by the workshop participants—in descending order starting with the most popular—included the following (Figure 1):

- Integrate data skills across the curriculum: This recommendation likely offers the most comprehensive approach to building skills as students complete courses toward a degree.

- Incorporate data management into 101 courses: Teaching data management in introductory level undergraduate courses could help to ensure broad exposure. A suggestion was to include lessons on foundational data science skills such as those vetted by The Carpentries.

- Include data management plans as part of class projects focused on writing proposals: Graduate students are often first exposed to writing proposals as part of their coursework. Including a data management plan as a project requirement could offer students preparation for future grant proposals to the many agencies and foundations that now require such plans.

- Incorporate a data management lecture by a data professional into a core science course required for the degree.

- Establish workshops for incoming students to work through data management topics: Offering a data skills workshop as part of orientation programming, especially to introduce incoming graduate students to their institution’s data library and computing infrastructure, could help connect students early on to resources helpful in their new research.

Some of these actions may be straightforward for individuals to implement in their own courses with local coordination, whereas others are broader and may require coordination at the degree or program level.

Some of these actions may be straightforward for individuals to implement in their own courses with local coordination, whereas others are broader and may require coordination at the degree or program level. Moreover, some of these recommendations overlap, and pursuing any combination of them, or any of them individually, could support early-career scientists.

Other actions proposed by participants mapped to the top five. For example, a suggestion related to integrating data skills across curricula was to create sequential learning experiences in which students encounter data skills instruction in a series of courses that progress from general to more disciplinary. Related to including a data management lecture in a core science course was an appeal for data professionals to volunteer themselves as guest lecturers in courses where the professor may not be savvy about data management.

Spurring Growth from the Bottom Up and Top Down

Scientists have long pondered whether the computing efficiencies predicted by Moore’s law will result in proportional advances in science by allowing them to leverage computing power to synthesize and analyze massive amounts of data quickly [Wooley and Lin, 2005]. Implicit in this vision of accelerating scientific advances is the assumption that scientists have the skills necessary to collect, organize, and publish standardized, well-documented data as part of their normal workflows. Some experts have candidly critiqued how far we are from fulfilling this assumption, citing an absence of data management training as one reason we are “drowning in data” [MacFadyen et al., 2022].

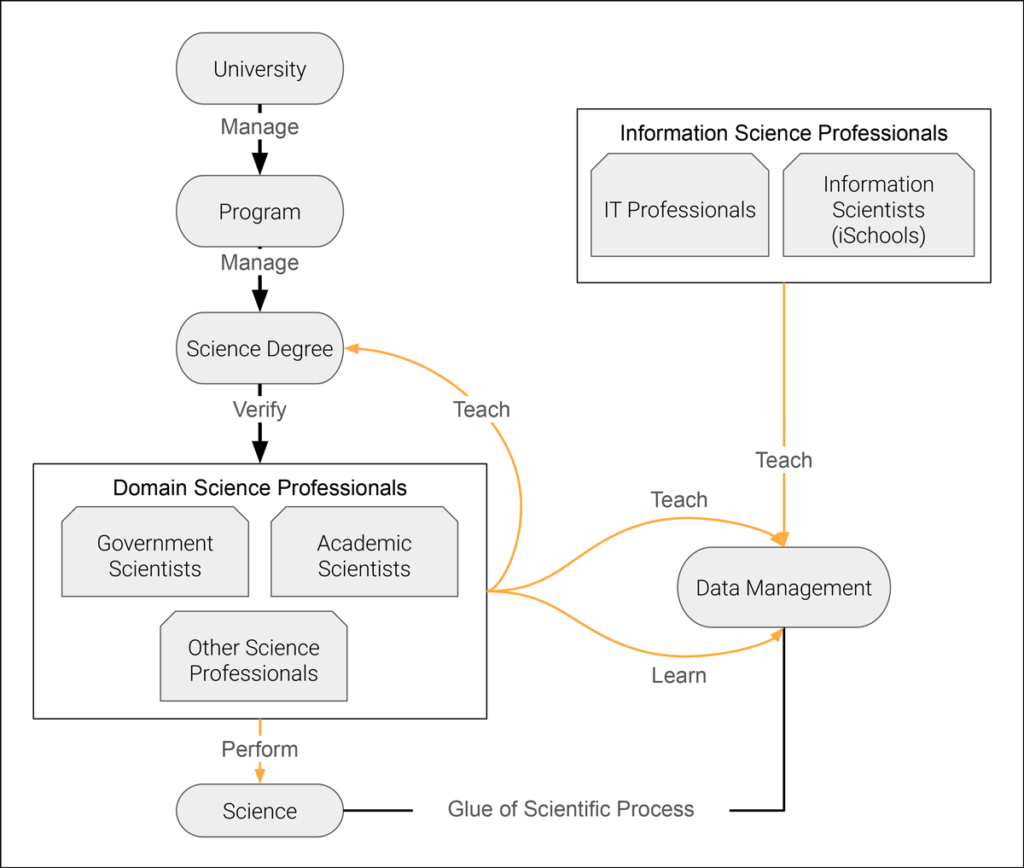

Strengthening connections between data support disciplines and domain science fields can help to ensure that competency with data management is a standard part of earning a science degree.

Brainstorming actionable ideas for change—as our session participants did—is a step in support of data management training, but constraints and obstacles to implementing these ideas exist. Perhaps foremost is the systemic undervaluing of data management as an essential skill of modern scientists [Tenopir et al., 2020]. In addition, instructors and programs constrained by time and resources may have limited capacity to implement changes, especially when balancing these changes with competing instructional demands.

Integrating RDM training into existing courses and curricula thus presents a challenge, although techniques like using real data to teach concepts can help accomplish it [Bristol and Pfeiffer-Herbert, 2024]. Resistance to the changing expectations for how data are managed and shared is another potential obstacle. These challenges are significant but surmountable with solid guidance and effort.

Strengthening connections between data support disciplines and domain science fields such as the Earth sciences can help to ensure that competency with data management is a standard part of earning a science degree, and it can help to support continued competency. A one-size-fits-all solution for making these connections does not exist. However, the diverse professional roles that scientists fill allow ample opportunities to support, build, and participate in systems that involve such connections, and individuals can consider how best to fill knowledge gaps they encounter (Figure 2).

Knowledgeable professionals across domains can teach RDM skills within their own institutions, for example, through a growing number of cross-departmental data science programs. They can also participate in informal or formal offerings through cross-institutional programs such as iSchools, an academic consortium focused on promoting information science, to help teach broader groups of untrained scientists the basics of RDM. Beneficiaries of data-focused training can further participate in teaching peers and students through informal education initiatives like The Carpentries.

Data professionals working outside domain sciences often have little agency to effect change in the curricula and programs used for training and credentialing professional scientists. Like-minded partners within these science programs can help to support efforts toward meaningful change. The recommendations from the 2023 ESIP meeting session can help guide these efforts.

Support from organizations like ESIP and AGU may also influence education across a broader, top-down scale. These organizations and other scientific societies can be guiding lights for educational institutions—by, for example, recommending that scientists document and demonstrate FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable) practices and mature data management skills in publications and presentations—and can serve as counterpoints to those working from the bottom up.

A goal is that with both bottom-up and top-down efforts by individuals and institutions, the time will come when the requisite knowledge and tools for responsible RDM are part of the fundamental skill set of modern scientists. As this future approaches, members of the scientific community can join these efforts and explore ways to increase data management literacy in the spaces where they work.

Acknowledgments

We thank speaker Michael Gravina and the more than 40 participants at our working session at the ESIP Meeting July 2023, including Mathew Biddle, Natalie H. Raia, and Robert R. Downs, who provided additional comments for this article. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

References

Aikat, J., et al. (2017), Scientific training in the era of big data: A new pedagogy for graduate education, Big Data, 5, 12–18, https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2016.0014.

Bishop, B. W., A. M. Orehek, and H. R. Collier (2021), Job analyses of Earth science data librarians and data managers, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102, E1,384–E1,393, https://doi.org/10.1175/bams-d-20-0163.1.

Bishop, B. W., et al. (2023), Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) liaison librarians: Perspectives on functions and frequencies for serving academic researchers, Libr. Inf. Sci. Res., 45, 101265, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2023.101265.

Bristol, D. L., and A. Pfeiffer-Herbert (Eds.) (2024), Ocean Data Labs: Exploring the Ocean with OOI Data, online laboratory manual, 2nd ed., Rutgers, State Univ. of N. J. [Accessed 11 July 2024], https://datalab.marine.rutgers.edu/ooi-lab-exercises/.

Demchenko, Y., and L. Stoy (2021), Research data management and data stewardship competences in university curriculum, in 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), pp. 1,717–1,726, Inst. of Electr. and Electron. Eng., Piscataway, N.J., https://doi.org/10.1109/educon46332.2021.9453956.

Donaldson, D. R., and J. W. Koepke (2022), A focus groups study on data sharing and research data management, Sci. Data, 9, 345, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01428-w.

Hoebelheinrich, N., and S. Hou (2016), Data management training via ESIP: Progress and possibilities, https://commons.esipfed.org/node/8908.

MacFadyen, S., et al. (2022), Drowning in data, thirsty for information and starved for understanding: A biodiversity information hub for cooperative environmental monitoring in South Africa, Biol. Conserv., 274, 109736, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109736.

Roberts-Pierel, B., E. Davis, and Y. Rao (2021), A graduate student’s road map for data management training, Earth Sci. Inf. Partners, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14384456.v1.

Schuster, D. C., et al. (2019), Challenges and future directions for data management in the geosciences, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 100, 909–912, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-18-0319.1.

Strasser, C. A., and S. E. Hampton (2012), The fractured lab notebook: Undergraduates and ecological data management training in the United States, Ecosphere, 3, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1890/ES12-00139.1.

Tenopir, C., et al. (2020), Data sharing, management, use, and reuse: Practices and perceptions of scientists worldwide, PLOS One, 15, e0229003, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229003.

Wooley, J. C., and H. Lin (Eds.) (2005), Catalyzing Inquiry at the Interface of Computing and Biology, 468 pp., Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, D.C., https://doi.org/10.17226/11480.

Author Information

Abigail Benson, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Palm Springs, Calif.; Stace E. Beaulieu, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Mass.; Bradley Wade Bishop, University of Tennessee, Knoxville; Stephen C. Diggs, University of California Office of the President, Oakland; and Stephen Formel ([email protected]), U.S. Geological Survey, Lakewood, Colo.