During the ninth century BCE, King Mesha reigned over Moab, a kingdom located in what is now Jordan. Details of how King Omri of Israel ruled the Moabites, Mesha’s subsequent rebellion, and numerous construction projects Mesha undertook as monarch were recorded on a slab of stone around 840 BCE.

The Moabite Stone, found in 1868 in modern-day Dhiban, Jordan, and now on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris, tells a story seemingly contemporaneous with one from the biblical Book of Kings, but from a different perspective. Artifacts that illuminate biblical times hold great importance for archaeologists, museums, and collectors—so much that forgeries fetch great sums.

Artifacts from the biblical era are so valuable that in one infamous example, an entire class of reproductions, the Moabite forgeries, was created soon after the discovery of the Moabite Stone. The Moabite forgeries consist of clay vessels, figurines, and other items crafted in the 19th century. Some are inscribed with Phoenician script selected from the real Moabite Stone. The inscriptions on the Moabitica, as the forgeries are called, translate to nonsense, and the clay used to fashion the frauds came not from Jordan but from clays around Jerusalem.

The Moabite forgeries and other fakes can be used to validate ways to authenticate archaeological finds. In a pair of studies that will be presented at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2025, Scripps Institution of Oceanography postdoctoral scholar Yoav Vaknin will explore ways to verify archaeological finds using something that’s hard to imitate—Earth’s paleomagnetic field.

A Record in Clay

Earth’s magnetic field, which has both a direction and a strength, changes over time. North and south swap poles every so often. The intensity of the field—how strong it is at a particular location or at a particular time—also rises and falls.

“You can use these changes as a dating tool for archaeology,” explained Vaknin. “But first, you need to know how it changed over time.” To that end, Vaknin and colleagues had previously conducted a study compiling paleointensity measurements of the magnetic field for well-dated antiquities at the time they were produced, painstakingly reconstructing how the intensity changed in and around the Levantine region.

“We can use this reconstruction of the field to date [an] object.” This technique is also how forgeries can be detected.

“Artifacts are known to be really good magnetic records in part because they’re fired to really high temperatures,” said Courtney Sprain, a paleomagnetist at the University of Florida who was not involved in this study. In the kilns and ovens that harden clay, temperatures can reach 1,200°C (2,192°F). At these temperatures, chemical reactions cause new minerals to form, including iron-rich magnetite that locks in the status of Earth’s magnetic field—both direction and intensity—at around 580°C (1,076°F). Because pots don’t remain in place after they’ve been fired, the direction isn’t especially useful. But the magnetic field’s intensity is.

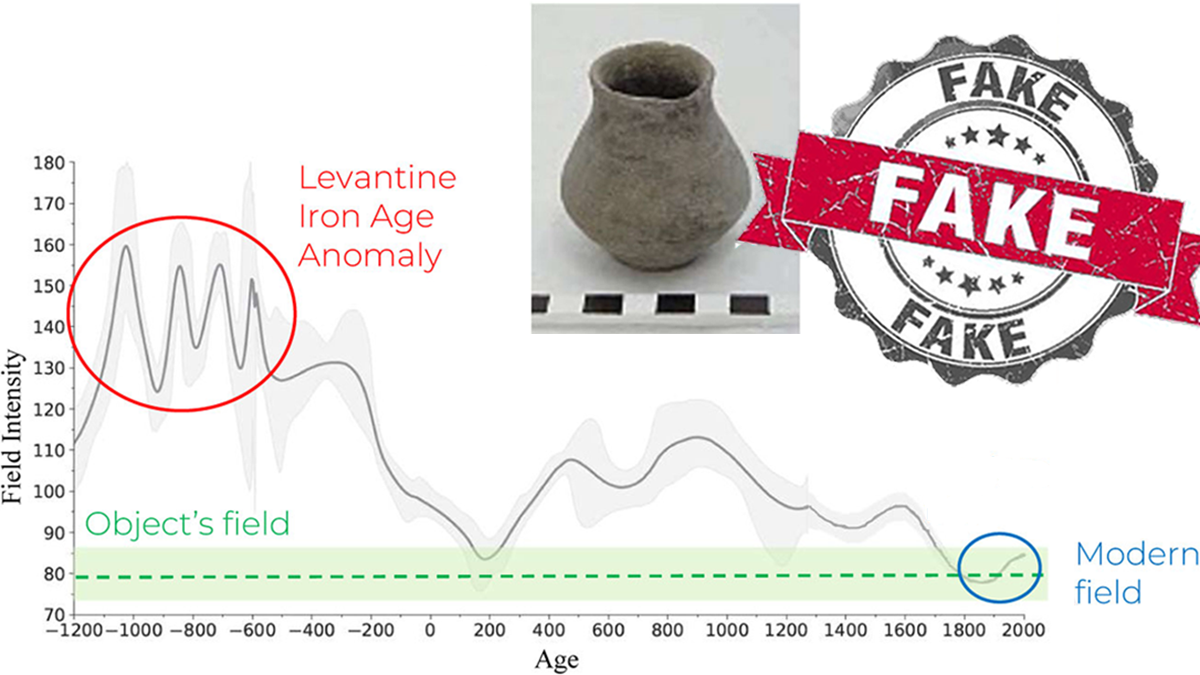

A marked increase in magnetic field intensity, more than twice that of today’s field, took place in the Levant from about 1050 to 700 BCE. Called the Levantine Iron Age anomaly, it has been documented across the region, recorded in artifacts and rocks from Cyprus, Israel, Jordan, Syria, and other locales.

Because the paleointensity timeline has been established for the region, “if we have materials that aren’t well dated, we can use this reconstruction of the field to date [an] object,” Vaknin said. This technique is also how forgeries can be detected.

Real or Fake

The Iron Age overlaps with much of the biblical period, Vaknin said. This is the time when many of the Bible’s stories—like those of King Mesha and King Omri—took place.

This time is an important part of human history, so people want these artifacts. As a result of this demand, Vaknin said, “they’re worth a lot of money.”

If an artifact comes to or from an antiquities market, private collection, or museum without information about the archaeological dig where it was excavated, “we don’t know how it got there,” said Vaknin. “There isn’t a method that’s really 100% secure to say if something is authentic.”

Researchers often disagree in their assessments of authenticity, with debates spilling into the academic literature about whether important items are legitimate or mere imitations.

If the artifact looks like it came from this time but has a magnetic field of today, “then it’s clearly fake.”

Measuring the paleomagnetic intensity of a disputed artifact can help archaeologists determine whether the artifact was made recently or during a time with a distinctly different paleomagnetic field than today’s. For instance, in Vaknin’s work, he demonstrates that forgeries were clearly fired at a time with today’s magnetic field intensity—not at the time of the Levantine Iron Age anomaly. If the artifact looks like it came from an earlier time but has a magnetic field of today, “then it’s clearly fake,” Vaknin said.

With this proof of concept, Vaknin and his colleagues have begun to look at artifacts of unknown authenticity that are under vigorous debate.

One limitation of the method is that it works only for authenticating artifacts from times when the paleomagnetic field was very different from the modern field, Vaknin cautioned. He and his colleagues are addressing that limitation by combining novel modeling and experiments related to how the magnetization of an item of interest can detectably change at low temperatures—the topic of another AGU25 presentation.

“This is one of the really cool examples of where [paleomagnetic] data can help with the study of archeology in general,” said Sprain regarding Vaknin’s work on using paleointensity. “Any artifacts that were from this area [and] from that time period, they have to have this strong magnetic signal.”

—Alka Tripathy-Lang (@dralkatrip.bsky.social ), Science Writer