A major part of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a large-scale ocean circulation pattern, was warmer during the peak of Earth’s last ice age than previously thought, according to a new study published in Nature.

The study’s results contrast with those from previous studies hinting that the North Atlantic was relatively cold and that AMOC was weaker when faced with major climate stress during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), about 19,000–23,000 years ago.

The findings add confidence to models that scientists use to project how AMOC may change in the future as the climate warms, said Jack Wharton, a paleoceanographer at University College London and lead author of the new study.

Deepwater Data

The circulation of AMOC, now and in Earth’s past, requires the formation of dense, salty North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW), which brings oxygen to the deep ocean as it sinks and helps to regulate Earth’s climate. Scientists frequently use the climatic conditions of AMOC during the LGM as a test to determine how well climate models—like those used in major global climate assessments—simulate Earth systems.

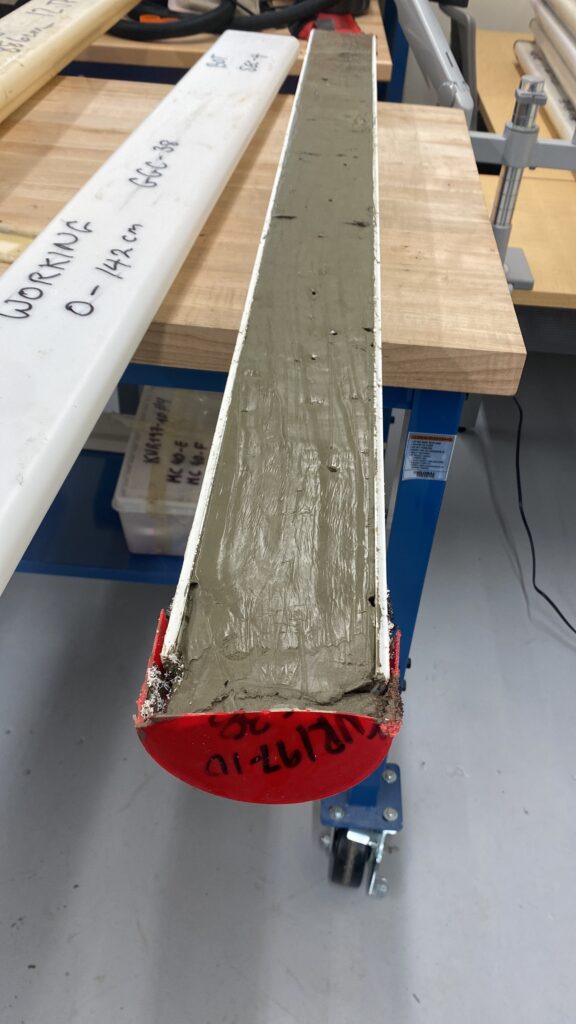

However, prior to the new study, few data points existed to validate scientists’ models showing the state of NADW during the LGM. Scientists in 2002 analyzed fluid in ocean bottom sediment cores from four sites in the North Atlantic, South Pacific, and Southern Oceans, with results suggesting that deep waters in all three were homogeneously cold.

“The deep-ocean temperature constraints during the [Last Glacial Maximum] were pretty few and far between,” Wharton said. And to him, the 2002 results were counterintuitive. It seemed more likely, he said, that the North Atlantic during the peak of the last ice age would have remained mobile and that winds and cold air would have cooled and evaporated surface waters, making them saltier, denser, and more prone to create NADW and spur circulation.

“This is quite new,” he remembered thinking. “What kind of good science could help show that this is believable?”

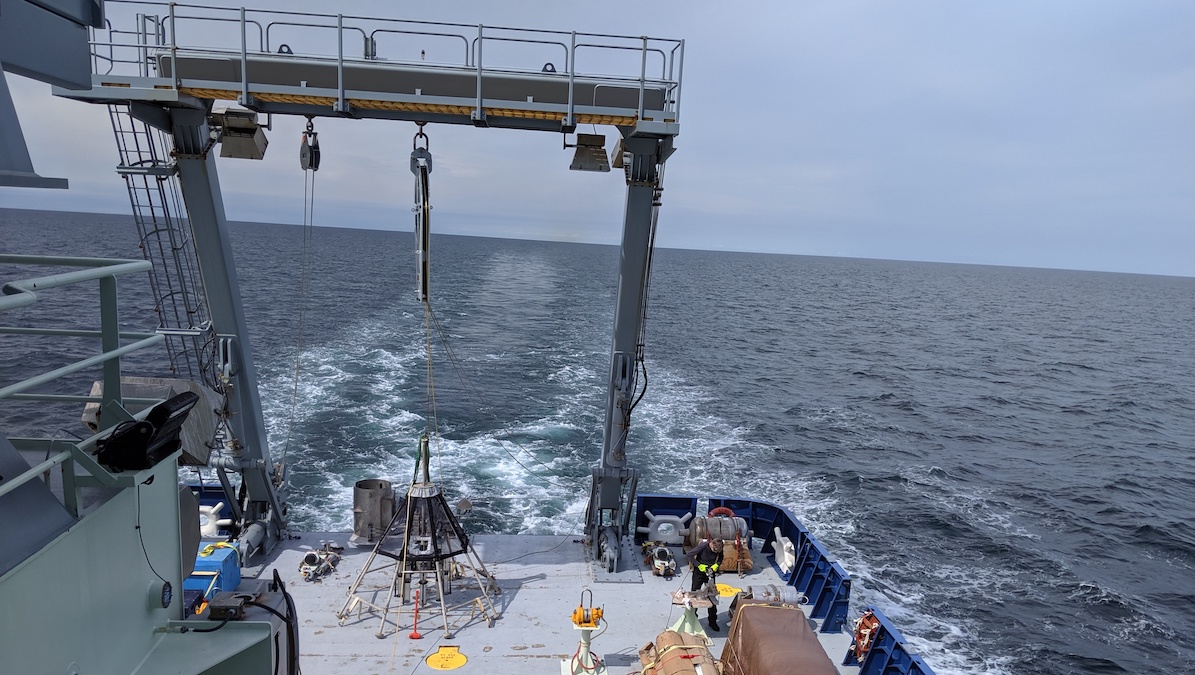

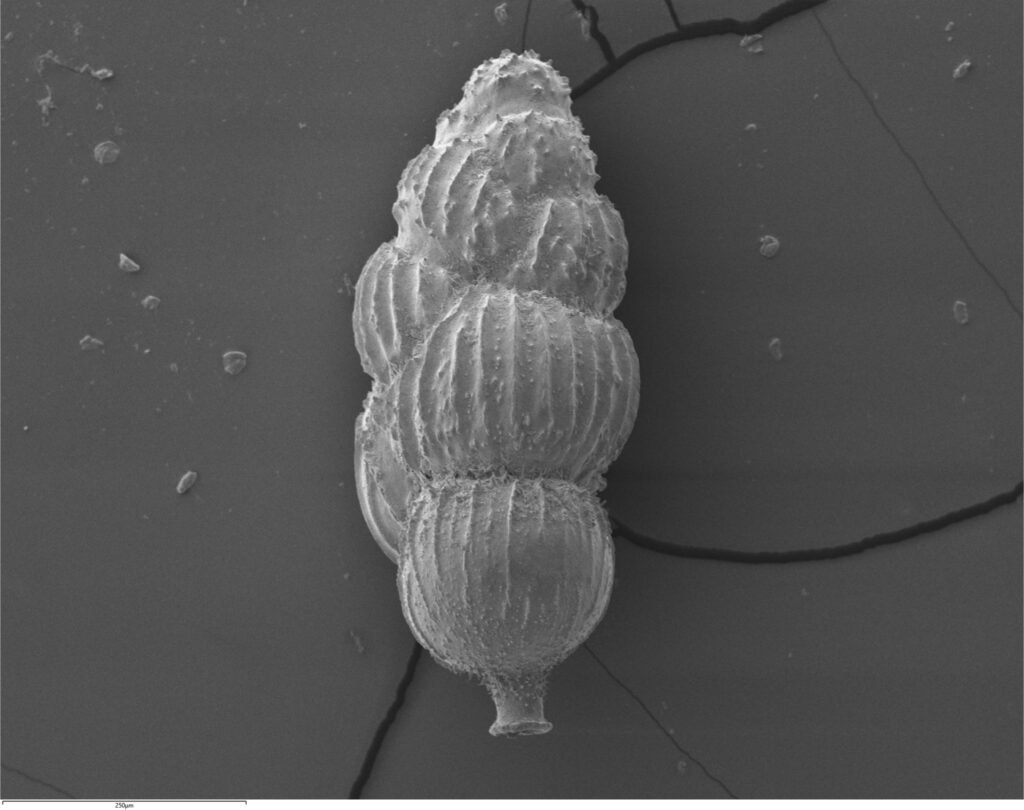

Wharton and his colleagues evaluated 16 sediment cores collected across the North Atlantic. First, they measured the ratio of trace magnesium and calcium in microscopic shells of microorganisms called benthic foraminifera. This ratio relates to the temperature at which the microorganisms lived. The results showed much warmer North Atlantic Deep Water than the 2002 study indicated.

Wharton felt cautious, especially because magnesium to calcium ratios are sometimes affected by ocean chemistry as well as by temperature: “This is quite new,” he remembered thinking. “What kind of good science could help show that this is believable?”

The team, this time led by Emilia Kozikowska, a doctoral candidate at University College London, verified the initial results using a method called clumped isotope analysis, which measures how carbon isotopes in the cores are bonded together, a proxy for temperature. The team basically “did the whole study again, but using a different method,” Wharton said. The results aligned.

Analyzing multiple temperature proxies in multiple cores from a broad array of locations made the research “a really thorough and well-done study,” said Jean Lynch-Stieglitz, a paleoceanographer at the Georgia Institute of Technology who was not part of the research team but has worked closely with one of its authors.

The results, in conjunction with previous salinity data from the same cores, allowed the team to deduce how the North Atlantic likely moved during the LGM. “We were able to infer that the circulation was still active,” Wharton said.

Modeling AMOC

The findings give scientists an additional benchmark with which to test the accuracy of climate models, Lynch-Stieglitz said. “LGM circulation is a good target, and the more that we can refine the benchmarks…that’s a really good thing,” she said. “This is another really nice dataset that can be used to better assess what the Last Glacial Maximum circulation was really doing.”

“Our data [are] helping show that maybe AMOC was sustained.”

In many widely used climate models, North Atlantic circulation during the LGM looks consistent with the view provided by Wharton’s team’s results, indicating that NADW was forming somehow during the LGM, Lynch-Stieglitz said. However, no model can completely explain all of the proxy data related to the LGM’s climatic conditions.

“Our data [are] helping show that maybe AMOC was sustained,” which helps reconcile climate models with proxy data, Wharton said. Lynch-Stieglitz added that a perhaps equally important contribution of the new study is that it removes the sometimes difficult-to-simulate benchmark of very cold NADW during the LGM that was suggested in research in the early 2000s. “We don’t have to make the whole ocean super cold [in models],” she said.

Some climate models suggest that modern-day climate change may slow AMOC, which could trigger a severe cooling of Europe, change global precipitation patterns, and lead to additional Earth system chaos. However, ocean circulation is highly complex, and models differ in their ability to project future changes. Still, “if they could do a great job with LGM AMOC, then we would have a lot more confidence in their ability to project a future AMOC,” Lynch-Stieglitz said.

Wharton said the results also suggest that another question scientists have been investigating about the last ice age—how and why it ended—may be worth revisiting. Many hypotheses rely on North Atlantic waters being very close to freezing during the LGM, he said. “By us suggesting that maybe they weren’t so close to freezing…that sort of necessitates that people might need to rethink the hypotheses.”

—Grace van Deelen (@gvd.bsky.social), Staff Writer