Time travelers to the Ediacaran can forget about packing a compass. Our planet’s magnetic field was remarkably weak then, and new research suggests that that situation persisted for roughly 3 times longer than previously believed.

That negligible magnetic field likely resulted in increased atmospheric oxygen levels, which in turn could have facilitated the observed growth of microscopic organisms, researchers have now concluded. These results, which will be presented at AGU’s Annual Meeting on Wednesday, 17 December, pave the way for better understanding a multitude of life-forms.

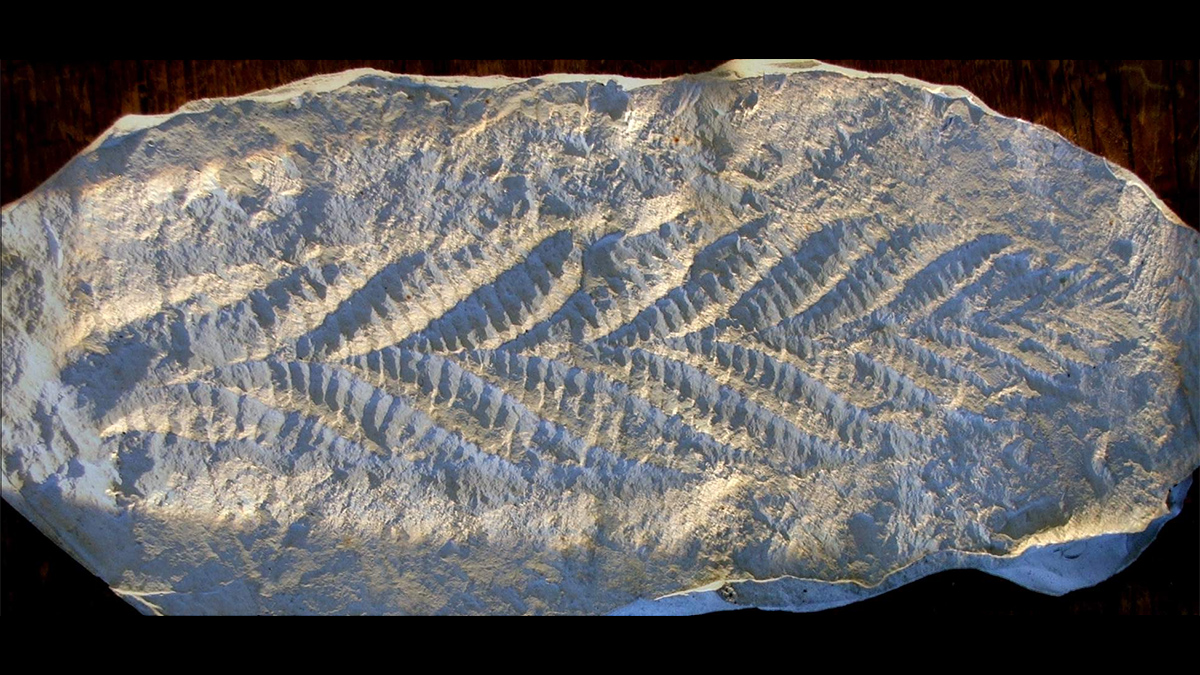

The Ediacaran period, which spans from roughly 640 million to 540 million years ago, is recognized as a time in which microscopic life began evolving into macroscopic forms. That transition in turn paved the way for the diversification of life known as the Cambrian explosion. The Ediacaran furthermore holds the honor of being one of the most recent inductees into the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, the official geologic timescale. (Last year, the Anthropocene was rejected as an addition to the International Chronostratigraphic Chart.)

A Collapsing Field, with Implications for Life

The Ediacaran was a time of magnetic tumult. An earlier study showed that our planet’s magnetic field precipitously fell from roughly modern-day values, decreasing by as much as a factor of roughly 30.

“We have this unprecedented interval in Earth’s history where the Earth’s magnetic field is collapsing.”

“We have this unprecedented interval in Earth’s history where the Earth’s magnetic field is collapsing,” said John Tarduno, a geophysicist at the University of Rochester involved in the earlier study as well as this new work.

The strength of our planet’s magnetic field has implications for life on Earth. That’s because Earth’s magnetic field functions much like a shield, protecting our planet’s atmosphere from being pummeled by a steady stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun (the solar wind). A weaker magnetic field means that more energetic particles from the solar wind can ultimately interact with the atmosphere. That influx of charged particles can alter the chemical composition of the atmosphere and allow more DNA-damaging ultraviolet radiation from the Sun to reach Earth’s surface.

There’s accordingly a strong link between Earth’s magnetic field and our planet’s ability to support life, said Tarduno. “One of the big questions we’re interested in is the relationship between Earth’s magnetic field and its habitability.”

We’re Getting Older (Rocks)

Tarduno and his colleagues previously showed that a weak magnetic field likely persisted during the Ediacaran from 591 to 565 million years ago, a span of 26 million years.

But maybe that period lasted even longer, the team surmised. To test that idea, the researchers analyzed an assemblage of 641-million-year-old anorthosite rocks from Brazil. Those rocks date to the late Cryogenian, the period immediately preceding the Ediacaran.

Back in the laboratory, the researchers extracted pieces of feldspar from the rocks. Within that feldspar, the team homed in on tiny inclusions of magnetite, a mineral that records the strength and direction of magnetic fields.

Team member Jack Schneider, a geologist at the University of Rochester, used a scanning electron microscope to observe individual needle-shaped bits of magnetite measuring just millionths of a meter long and billionths of a meter wide. “We can see the actual magnetic recorders,” said Schneider.

Working in a room shielded from Earth’s own magnetic field, Schneider measured the magnetization of feldspar crystals containing those magnetite needles. To ensure that the magnetite needles were truly reflecting Earth’s magnetic field 641 million years ago rather than a more recent magnetic field, the team focused on single-domain magnetite. A single domain refers to a region of uniform magnetization, which is much more difficult to overprint with a new magnetic field than a region magnetized in multiple directions. “We make sure that they’re good samples for us to use,” said Schneider.

Don’t Blame Reversals

The average field strength that the team recorded was consistent with zero, with an upper limit of just a couple hundred nanoteslas. “Those are the type of numbers you measure on solar system bodies today where there’s no magnetic field,” said Tarduno. For comparison, Earth’s magnetic field today is several tens of thousands of nanoteslas.

Given the weak magnetic field strengths dating to 565 million years ago and 591 million years ago and these new measurements of rocks from 641 million years ago, there might have been a roughly 70-million-year span in which Earth’s magnetic field was unusually feeble and possibly nonexistent, the team concluded.

And magnetic reversal—the periodic switching of Earth’s north and south magnetic poles—isn’t the likely culprit, the researchers suggest. It’s true that the planet’s magnetic field drops to very low levels during some parts of a magnetic reversal, but that situation persists for at most a few thousand years, said Tarduno. That’s far too short a time to show up in this dataset—the rocks that the team measured all cooled over tens of thousands of years, so the magnetic fields they recorded are an average over that time span.

Take a Deep Breath

If it’s true that Earth’s magnetic field was anomalously weak for about 70 million years, cascading effects might have helped prompt the transition from microscopic to macroscopic life, the team suggests. That shift, known as the Avalon explosion, preceded the better-known Cambrian explosion.

In particular, a weak magnetic field would have allowed the solar wind to impinge more on our planet’s atmosphere, a process that would have preferentially kicked out lighter inhabitants of the atmosphere such as hydrogen. Such a depletion of hydrogen would have, in turn, boosted the relative concentration of an important atmospheric species: oxygen.

“If you’re removing hydrogen, you’re actually increasing the oxygenation of the planet, particularly in the atmosphere and the oceans,” explained Tarduno. And because oxygen plays such a key role for so many species across the animal kingdom, it’s not too much of a stretch to imagine that the important life shift that occurred soon thereafter—miniscule creatures evolving into ones that measured centimeters or even meters in size—owes something to the invisible actor that is our planet’s magnetic field, the team concluded. “We passed a threshold that allowed things to get big,” said Tarduno.

It’s difficult to test this hypothesis by measuring ancient atmospheric oxygen levels, the team admits. (The ice cores that famously record atmospheric gases stretch back in time just about a million years, give or take.)

But this idea that the planet’s magnetic field may have triggered atmospheric changes that in turn played a role in animals growing larger makes sense, said Shuhai Xiao, a geobiologist at Virginia Tech not involved in the research. “If the oxygen concentration is low, you simply cannot grow very big.”

In the future, it will be important to fill in our knowledge of the magnetic field during the Ediacaran with more measurements, added Xiao. “One data point could change the story a lot.”

Cathy Constable, a geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography not involved in the research, echoed that thought. “The data are sparse,” she said. But this investigation is clearly a step in the right direction, she said. “I think this is exciting work.”

—Katherine Kornei (@KatherineKornei), Science Writer