Source: Geophysical Research Letters

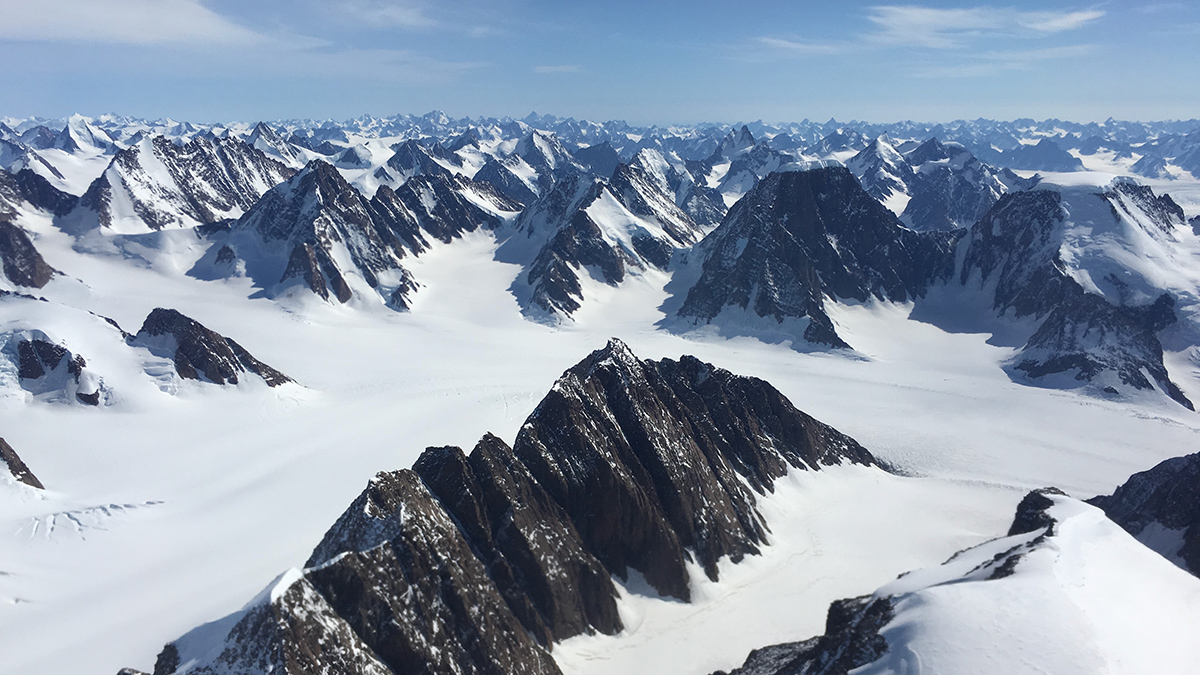

Mapping Greenland’s geology is no easy feat. The Greenland Ice Sheet, which covers more than 1% of Earth’s land surface and nearly 80% of Greenland’s landmass, obscures much of the island’s subglacial geology. As a result, scientists have largely interpolated the island’s geology from rocks exposed at the ice sheet’s margins.

In 2009, Peter Dawes of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland produced the island’s landmark geologic map, which is still widely used today. The map has served as a critical tool for documenting geologic characteristics and meaningfully evaluating economic resources on the world’s largest island. In recent years, however, technological advances in seismic imaging, geophysical surveys, and satellite mapping of gravity and magnetic anomalies have created opportunities to improve Greenland’s geologic map.

MacGregor et al. used these advancements to redraw Greenland’s geologic provinces. Pulling from 19 data sets, the authors delineated an updated map of Greenland’s subglacial geology. Additionally, they introduced a novel “flow-aware” hillshade (a method for highlighting terrain on a map) based on the idea that an ice mass transfers a topographic signature from the land over which it flows to its surface.

The resulting geologic map clarifies the extent of Greenland’s geologic provinces and confirms that a greater variety of provinces exists in northern Greenland than in southern Greenland. Three distinct subglacial regions could not be reconciled with the geology at the island’s margins. In addition, newly mapped geologic structures offer updated perspectives on how ice flows from Greenland’s interior toward the coast.

The mapping effort also revealed dozens of unusually long, straight, nearly parallel valleys beneath the ice. These valleys are not captured by current syntheses of Greenland’s subglacial topography, which raises the possibility that tectonics may have influenced the island’s geology more than previously realized.

The authors acknowledge that the updated geological map is an incomplete representation of Greenland’s subglacial geology—and that nothing beats eyes and boots on the ground to examine the rocks present. Nevertheless, the work offers a modernized framework for interpreting the landmass’s subglacial and solid Earth properties that can be incorporated into a variety of related scientific disciplines. (Geophysical Research Letters, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL107357, 2024)

—Aaron Sidder, Science Writer