From medicine to space travel, three-dimensional (3-D) printing has captured the minds of scientists everywhere. Now, a pair of researchers is applying the technology to planetary surfaces, giving scientists, educators, and students novel tools for understanding faraway terrains and what their shapes tell us.

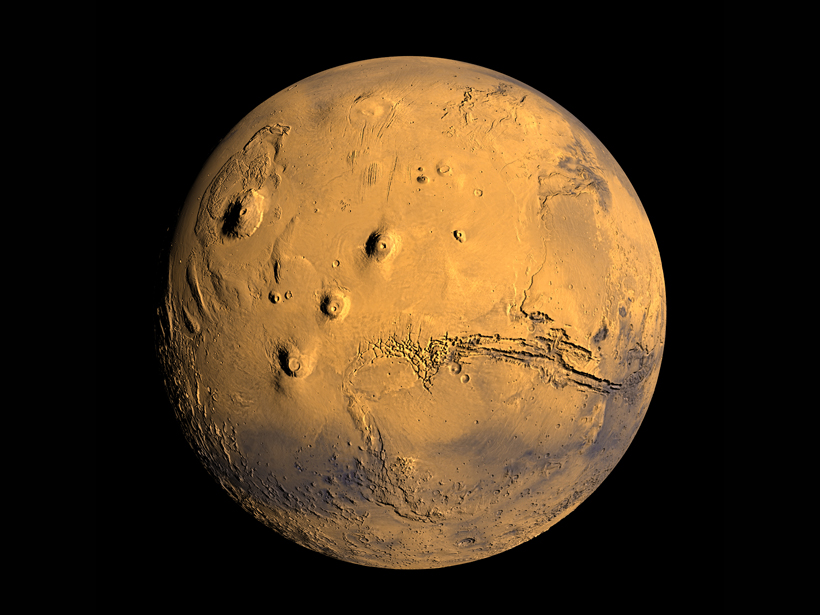

At a poster presentation at the annual Geological Society of America (GSA) conference in Baltimore, Md., two scientists showed off 3-D models of impact craters on the Moon and Mars, as well as of Mars’s Valles Marineris canyon. These sorts of models, they said, allow researchers and students to add new dimensions to how they teach and learn.

“We’ve had open houses for middle school kids, and we always have a puddle of them staring fixedly.”

“We’ve had open houses for middle school kids, and we always have a puddle of them staring fixedly” at the models, said Seth Horowitz, who originally trained as a neuroscientist but started collaborating with a Brown University astronomer in 2011 on printing the models. “Students who haven’t been exposed to 3-D printing are just mesmerized by them.”

Horowitz started collaborating with Peter Schultz, the director of the Northeast Planetary Data Center, who originally helped fund Horowitz’s 3-D printing venture through Brown University’s Rhode Island Space Grant program, using a 3-D printer they built from a kit. At the GSA conference in 2012, they had the sole 3-D printer. However, this year an entire row of posters covered the use of 3-D models in geophysical research, including volcanology, crystallography, and hydrology. This shows the growing potential for this technology, Schultz said.

Learning Potential

“It’s great to be able to look at a fantastic animation of sunrise over a Martian valley, but being able to pick up a physical model and move it around … all without having to learn another piece of software or needing yet another java update before it works, enhances our understanding of the places,” Horowitz said.

Schultz specializes in studying impact craters around the solar system, including on Earth. Three-dimensional models can show subtle structures that tell scientists intimate details about a crater, including at what trajectory an impactor hit a planet or what existed around the environment where it hit, he said.

For example, studying a 3-D model of Mars’s Gale Crater helped Schultz see what might be a relic rim of a previously existing crater at that location. He suspected that the relic rim was there, but it wasn’t until he held the model in his hands that the evidence jumped out at him. Having the physical model also helped Schultz communicate his thoughts to other scientists, he said.

“Having the 3-D model amplifies what we’re trained to see with contour maps [and] surface feature maps.”

In Earth science, in particular, 3-D modeling technology can apply to many fields, Schultz said. Visualizing a landscape or geological feature is one thing, but actually holding it in your hand is a completely different experience, especially for students who are visually impaired. Scientists could even incorporate cross sections into their models to help demonstrate and research the intricate interactions of underground processes, he said, like faults and folding.

“Having the 3-D model amplifies what we’re trained to see with contour maps [and] surface feature maps,” Schultz said.

From Data to Models

Schultz and Horowitz print the models using data from the various satellite missions orbiting Mars and the Moon. These satellites map the surface of a planetary body using radar or lidar to produce digital models, which they then convert into data that can be read by a standard 3-D printer. They also provide 3-D printing data that other scientists can use.

Any scientist with a 3-D printer and the right data could print their own models for students and researchers, Horowitz said.

Schultz hopes that one day, every Earth or space science professor will have a 3-D model of a favorite feature from the solar system to use to help educate students and colleagues.

“The challenge now is to turn this into something more than toys or giveaways,” he continued. “It’s really important to be able to turn this into something usable and I think we’re just at the [edge] of that.”

—JoAnna Wendel, Staff Writer

Citation: Wendel, J. (2015), 3-D models put scientists, students in touch with planets, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO039361. Published on 11 November 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.