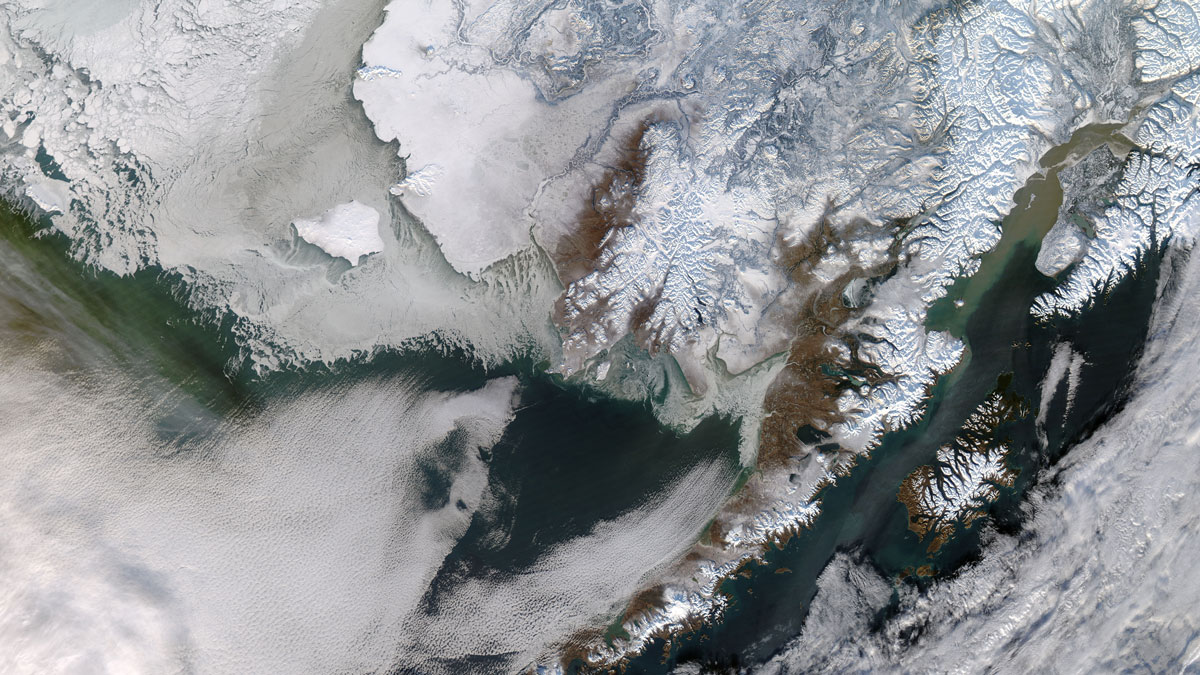

In Alaska, winter is more than a season—it is survival. For Indigenous communities in Aniak, St. Mary’s, and Elim, snow and frozen rivers guide travel, hunting, and fishing. But those conditions are becoming less reliable in the Arctic, the fastest-warming region on Earth.

“The spring and the fall seasons are crunching in on the time frame where there’s enough snow and safe conditions to be able to move around,” said Helen Cold, a subsistence resource specialist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Indigenous communities “know their river better than anyone else in the world.”

With the Arctic Rivers Project, scientists and community leaders are racing to track changes in Alaska’s winters and plan for the future. By combining Indigenous Knowledges with high-resolution climate models, a team is working to build a collection of “storylines” to capture winter shifts and serve as tools for adaptation.

“There’s been a big movement in climate science to use narrative approaches to describe impacts,” said University of Colorado Boulder hydrologist Keith Musselman, who will present the research with his team on 15 December at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2025 in New Orleans. After all, Indigenous communities “know their river better than anyone else in the world.”

Voices from the River

Musselman and his colead, Andrew Newman, a hydrometeorologist at the National Science Foundation’s National Center for Atmospheric Research, leaned on local leadership by creating an Indigenous Advisory Council of 10 regional representatives. The council shaped research questions and ensured Indigenous Knowledges guided methods, data, and interpretation throughout the project.

To understand initial concerns, the research team convened the 2022 Arctic Rivers Summit to hear directly from community members. During the summit, council members emphasized the importance of inclusive planning to address climate change in ways that safeguard both people and ecosystems. In conjunction with the summit, interviews and workshops captured observations of shorter winters, thinner snowpack, midwinter thaws, and hazardous river ice. One respected elder and 15-time Iditarod racer shared that in his lifetime, he has witnessed more intense snowfall events and reduced snow persistence. Some communities also voiced concerns about more frequent coastal storms and shifts in wildfire patterns driven by lightning during dry periods.

Such shifts have major consequences, including reduced food security for Indigenous people who rely heavily on the land. Michael Williams, an Aniak tribal advocate and Indigenous Advisory Council member, said these climatic changes “make our hunting practices very dangerous.” Over the past 20 to 40 years, he has observed extreme temperatures in the area and a nearly 50% reduction in ice thickness on nearby rivers—changes that make traveling and hunting mammals, migratory birds, and fish a serious challenge.

“It has changed everything here,” Williams said. “It’s affecting our ways of life.”

Bridging River Wisdom and Climate Data

Researchers compared community observations with data from historical records, satellite measurements, and U.S. Geological Survey sensors to recreate past conditions and generate six climate scenarios for Alaska’s winters from 2035 to 2065. Beyond standard climate indicators like air temperature, the chain of models simulated hydroclimatic patterns such as streamflow, snowmelt timing, river ice dynamics, and fish population conditions.

Records corroborated what communities had observed for years, and the models indicated even harsher changes could be ahead, although northern regions could see increased snowpack as winter precipitation rises. Translating these results into usable guidance requires careful planning. Communities were both concerned and curious when shown initial results, asking to compare conditions across regions to understand what their neighbors were experiencing.

“If we don’t include [Indigenous voices], then we’re dead. We’re good as dead.”

The initial phase of the project, which involved gathering and analyzing information, ended in 2024. But to support effective, accessible communication, the team will continue codeveloping “narratives of change” that weave together datasets, Indigenous Knowledges, and lived experience. They’re also exploring how tools like maps and Facebook channels can help share science with affected communities, with the goal of supporting intuitive, locally led adaptation as climate change reshapes life in Alaska.

Past adaptation strategies have often fallen short in including Native realities, said Cold, who was not involved in the research. She thinks the Arctic Rivers Project’s approach is a step in the right direction toward more inclusive climate planning.

Community leaders echo that sentiment and emphasize the urgency of such efforts. “Mitigation planning has to be ongoing in our communities for the survival of our people,” Williams said. “If we don’t include [Indigenous voices], then we’re dead. We’re good as dead.”

—Cassidy Beach, Science Writer