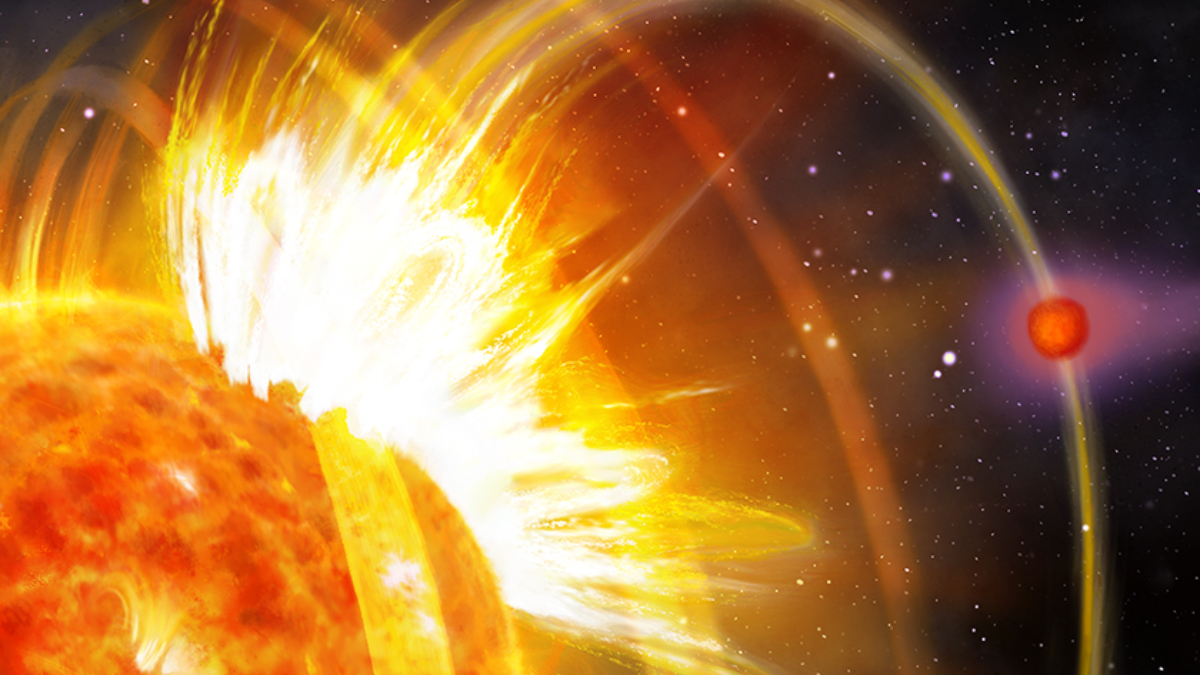

As giant planet HIP 67522 b orbits its host star, it triggers its own doom. The planet orbits HIP 67522, a young star slightly larger than the Sun, in just 7 Earth days. At just 17 million years old, the star is far more active than our Sun, regularly flaring and releasing massive amounts of energy and stellar material.

By using observations from three exoplanet telescopes, scientists have found that these flares don’t occur at random times and locations like on our Sun. Instead, they are concentrated at a particular time in the planet’s orbit, which suggests that the planet itself could be triggering the flares. What’s more, the flares are also pointed at the planet, bombarding it with nearly 6 times more radiation than it would experience if the flares occurred at random.

“We want to understand the space weather of these systems in order to understand how planets evolve over time, how much high-energy radiation they get, how much wind they’re exposed to, what consequences that has on the evolution of their atmospheres, and, down the line, habitability,” said Ekaterina Ilin, lead researcher on the discovery and an astronomer at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) in Dwingeloo.

Magnetic Interactions

Space weather is common in our solar system. At Earth’s relatively safe distance from the Sun, space weather manifests as aurorae and enhanced solar wind that, nonetheless, can wreak havoc on navigation and communication systems.

But in exoplanet systems, space weather can be far more deadly. Stars have strong magnetic fields, which are even stronger and more turbulent when stars are young. A star’s magnetic field lines stretch out from its surface, carrying superheated plasma along with them. Field lines regularly twist and tangle and coil until they eventually snap back into place, releasing stored energy and stellar material in a flare or coronal mass ejection (CME).

Astronomers have observed exoplanets orbiting so close to their stars that their atmospheres or even rocky surfaces are being blasted away by intense stellar radiation, winds, and flares. But for decades, astronomers have theorized that the connection between stars and close-in planets can go both ways.

According to the theory, some planets orbit so close to their star that they are inside the star’s magnetic boundary, the so-called sub-Alfvénic zone. Such a so-called short-period planet could gather up magnetic energy like a windup toy as it orbits and release it in waves along the star’s magnetic field lines. When the energetic waves reach the star’s surface, they could trigger a flare back toward the planet.

The idea was born after the discovery of the first exoplanet—51 Pegasi b—in 1995 showed astronomers that planets could orbit extremely close to their host stars (51 Pegasi b has a 4.23-day orbit). Ilin said that although the theory has existed since the early 2000s, it has taken a while to find even one exoplanet that might fit the bill because most planets discovered thus far orbit much older stars with few flares and weak magnetic fields.

Too Close for Comfort

Ilin and her colleagues combed through thousands of confirmed and candidate exoplanets detected by the now-retired Kepler Space Telescope and the extant Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). They looked for young, flaring stars with close-in giant planets—a very broad search with hundreds of results—and narrowed their search down by looking for planets that might orbit within the sub-Alfvénic zone and for stars with strange flare timings.

“It was really a shot in the dark,” Ilin said.

After a long, tedious search, the team homed in on HIP 67522 and its two planets: planet HIP 67522 b, with its 7-day orbit, and a second giant planet with a 14-day orbit. The star’s flares were clustered together, but only barely within the margin of significance.

“The expectation was that it would have one of the strongest magnetic interactions based on how close the star is to the [inner] planet, how big the star is, how big the planet is, how young it is, [and] how strong a magnetic field we expect,” Ilin said. Despite the marginal significance, she thought, “Oh, actually, it might be worth a second look.”

“Statistically, almost impossible.”

The researchers observed the star with the European Space Agency’s Characterising Exoplanets Satellite (CHEOPS) for 5 years. They characterized 15 stellar flares during that period, a typical number for this size and age of star, but found that the flares clustered together when the innermost planet passed between the star and the telescope’s vantage point at Earth.

“When the planet is close to transit, the flaring goes up by a factor of 5 or 6, and that should not happen,” Ilin explained. “Statistically, almost impossible.”

“It is fascinating to see clustered flaring following the planet as it orbits its star,” said Evgenya Shkolnik, an astrophysicist at Arizona State University in Tempe who was not involved with this research. Some of Shkolnik’s past work investigated enhanced stellar activity in Sun-like stars with hot Jupiters, but those stars were much older and did not flare as much as HIP 67522. “It makes sense that more flares could be triggered through the same type of magnetic star-planet interactions we observed,” she said.

“It makes its life even worse by whipping up this interaction…and firing all these CMEs directly into the planet’s face.”

Like other short-period giant planets, HIP 67522 b likely would have been losing its atmosphere to stellar radiation no matter what because of how closely its orbits—indeed, the planet is about the size of Jupiter but just 5% its mass. But because the flares are synced with HIP 67522 b’s orbital period, Ilin’s team calculated that HIP 67522 b is experiencing roughly 6 times the stellar radiation that it would if the flares were randomly distributed, and the corresponding CMEs are pointed directly at it.

The team’s simple estimates show that because of this increased radiation, the planet is losing its atmosphere about twice as fast as it would otherwise.

“It makes its life even worse by whipping up this interaction…and firing all these CMEs directly into the planet’s face,” Ilin said. These results were published in Nature.

“This discovery is extremely exciting,” said Antoine Strugarek, an astrophysicist at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission in Paris who was not involved with the research. “Such magnetic interactions are clearly the prime candidate to explain the observed phenomenon, and no other theories are really convincing to explain these observations, to the best of my knowledge.”

Expanding the Search

Strugarek explained that the magnetic interaction observed in the HIP 76522 system has a few analogs in our own solar system. The Sun experiences “sympathetic flares,” he said, in which a solar flare in one spot can trigger another one nearby—they account for about 5% of solar flares. And in the Jupiter system, the Galilean moons Io, Ganymede, and Europa propagate waves along their orbits that trigger polar aurorae on Jupiter.

For HIP 76522, “the theory is that the perturbation originates from the exoplanet. This is definitively a possibility, and extremely exciting for future research,” Strugarek said. He added that he would like to see future work constrain the geometry of HIP 76522’s magnetic field to better understand the star-planet connection.

“We need to scrutinize all the compact star-planet systems with large flares for such occurrences. This should be ubiquitous for very compact systems.”

He also wants to go back into the archives to look for more exoplanets like this. “Now that we have one tentative system, we need to scrutinize all the compact star-planet systems with large flares for such occurrences,” Strugarek said. “This should be ubiquitous for very compact systems.

Shkolnik added, “I would love to see dedicated observing programs at both higher- and lower-energy wavelengths, namely, in the far-ultraviolet, submillimeter, and radio wavelengths.” The far ultraviolet is more sensitive to flares, and finding more flares might confirm the theory that the planet is triggering them.

Thus far, HIP 76522 b is the only planet discovered to be magnetically influencing its star. Ilin said that when her team started looking into HIP 76522 b, it was the youngest short-period planet in their catalogs. TESS has since observed several more, and Ilin’s team is ready to investigate them.

The researchers also hope to flip the script on star-planet interactions. Instead of starting with an exoplanet and looking for clustered stellar flares, they want to first look for flare patterns and then find the planet causing them. The untested technique could detect exoplanets around stars that other detection methods struggle with: young, active stars.

“It is a bit of a statistically tough cookie,” she said, “but it will be quite exciting if we can make that happen.”

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@astrokimcartier.bsky.social), Staff Writer