Early in the time-twisting, exoplanet-exploring film Interstellar, a scientist on a blight-plagued Earth stares at corn in a greenhouse, watching the crop die. That scene, said Northern Arizona University doctoral candidate Laura Lee, got her thinking about growing food in difficult soils.

The idea propelled Lee, a planetary scientist and astronomer, into a new project, studying how the outer veneer of planetary bodies might be enriched to sustain crops needed for future human settlements. At AGU’s Annual Meeting 2025 on 16 December, Lee will present findings about how various amendments, such as fungi, urea-based fertilizer, and even poop, could help plants like corn grow on the Moon and Mars.

Necessary Ingredients

Plants need 17 specific elements to survive. Carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen combine to form cellulose—the building blocks of cell walls. Nitrogen helps lush green leaves flourish. Phosphorous stimulates stability-providing roots. Iron, potassium, and other nutrients are also critical for plants to function.

“If you can avoid bringing all that up, it’s super advantageous. Mass is really expensive.”

But on the Moon and Mars, the regolith—the loose outer layer of any planetary body—lacks some of these plant essentials. For instance, lunar regolith contains almost no carbon or nitrogen, said Steve Elardo, a planetary geochemist at the University of Florida who was not involved in Lee’s study.

Plus, the phosphorus that is present, at least on the Moon, isn’t in a useful form for plants, said Jess Atkin, a doctoral candidate and space biologist at Texas A&M who studies how microbes can remediate regolith to grow plants on the Moon.

Taking terrestrial soil to space is not ideal because of cost. “If you can avoid bringing all that up, it’s super advantageous,” Elardo said. “Mass is really expensive.” Taking microbes to the Moon, on the other hand, is a much lighter option.

What’s in a Regolith?

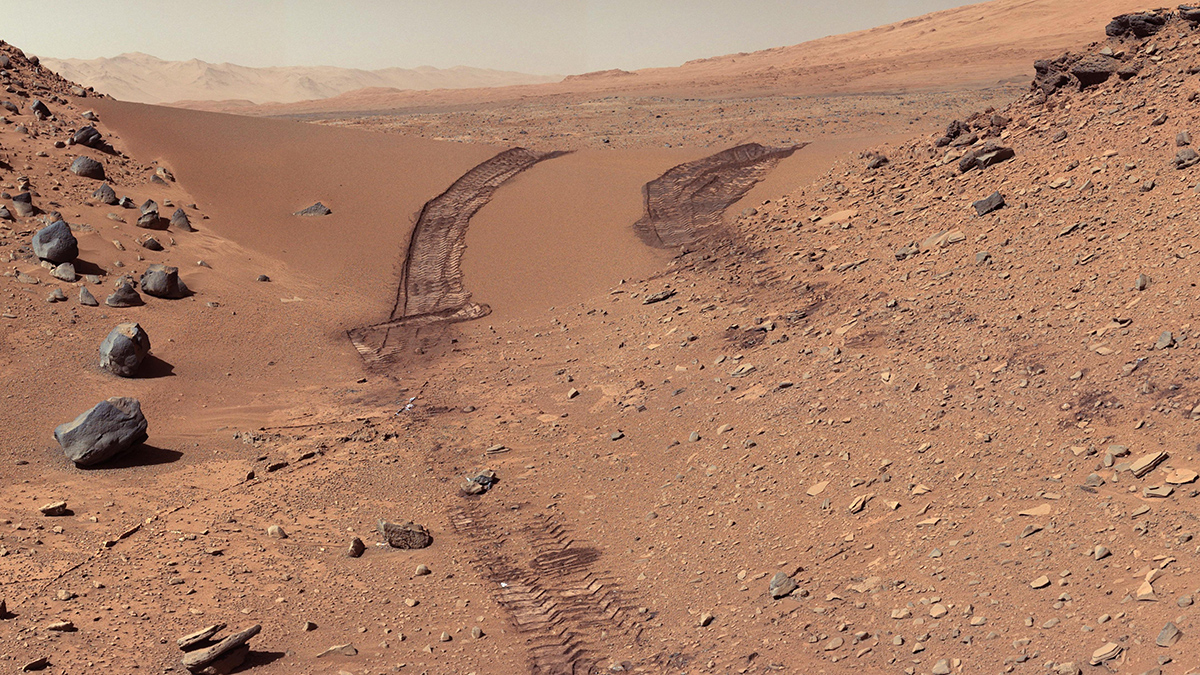

Scientists rely on data from rovers, landers, and satellite remote sensing to understand the chemistry of Martian regolith. The Apollo missions brought back 382 precious kilograms (842 pounds) of the Moon. The Chang’e and Luna missions combined brought back another ~4 kilograms of lunar samples. Because of the limited supply of real lunar regolith, most planetary crop studies, including Lee’s, rely on something called simulant, a synthetic imitation of extraterrestrial regolith.

For her experiments, Lee selected two simulants from Space Resource Technologies: one of the lunar highlands and one that approximates Martian regolith on the basis of data from both remote sensing and the Curiosity rover. But because of the lack of necessary nitrogen in both simulants, Lee tested two nitrogen-bearing media to introduce this key ingredient.

For the first, she used a synthetic urea-based fertilizer used by many home gardeners. For the second, Lee used Milorganite—a nitrogen-rich biosolid made from processing human waste produced by the population of Milwaukee, Wis. For Lee, the Milorganite imitates a nutrient-rich resource that future astronauts heading to planetary bodies will certainly have and that shouldn’t add weight to the mission payload: their own waste.

“When they’re adding human waste, the best thing they’re doing is adding organic matter” that can also help bind regolith particles together, said Atkin, who was not involved with Lee’s study.

“You can go full Mark Watney on this,” said Elardo, referencing the 2015 film The Martian, in which a botanist astronaut amends Martian regolith with the crew’s biosolids to grow potatoes. “If you compost [astronaut waste] and make it safe…it should provide a pretty good fertilizer.”

Fabulous Fungi

Lee also tested how crops grew with and without arbuscular mycorrhizae, a microscopic, symbiotic interconnection between certain fungi and the plant roots in which they reside.

“It extends that root zone, giving stability,” Atkin said, “like a glue in our soil.” The plant provides carbon to the fungi, and the fungi transfer water and nutrients, particularly phosphorus, to the plant, she explained.

In the fertilizer-only experiments, Lee found that plants grown in lunar simulant with Milorganite tended to grow larger, but in comparison, plants grown in lunar simulant with urea-based fertilizer were more likely to survive the 15-week growing period. For the Martian simulant, no plants survived in Milorganite.

There is a huge ethical question about bringing microorganisms to extraterrestrial places.

The fertilizer-only experiments provided a control to help Lee assess what happens with the addition of fungi. In the lunar experiments with fungi, no matter which nitrogen fertilizer source was used, plants grew larger than in the fertilizer-only trials. Lee also found higher chlorophyll levels in the leaves of plants grown with fungi and Milorganite. These results are signs that fungi facilitate healthier plants. Plants grown in Martian simulant amended with either fertilizer option also fared better with the addition of fungi. Although only a single plant out of six survived in Martian simulant amended with Milorganite and arbuscular mycorrhizae, this plant “produced the highest chlorophyll levels across all lunar and Martian corn, and produced the most biomass out of all plants grown in Martian regolith,” Lee wrote in an email.

“There is a huge ethical question about bringing microorganisms” to extraterrestrial places, said Lee, whether in the form of fertilizer or fungi. But any future astronauts will introduce microorganisms to the Moon and Mars via their own microbiomes, she said. Plus, 96 bags of human waste already languish on the lunar surface, divvied up between the six Apollo landing sites.

Simulant Versus Regolith

In an experiment published in 2022, a team of scientists including Elardo demonstrated that lunar regolith collected during Apollo 11, 12, and 17 could grow a plant called Arabidopsis thaliana, or thale cress. But the plants were stressed. “They grew, but they were not particularly happy,” Elardo said. The same plants produced healthy roots and shoots when grown in lunar simulants.

These findings demonstrated that for biology purposes, “[simulants] don’t capture the chemistry of extraterrestrial regoliths,” Elardo said, in part because that’s not always what simulants are designed to do. Several are made by the truckload for large-scale engineering projects, like testing the wheels of a rover destined for Mars, he explained. Moreover, the Moon’s iron isn’t in the same state as Earth’s, and it’s a version plants don’t want. Plus, real lunar regolith grains are extremely sharp and shard-like, impeding the progress of delicate roots.

Nevertheless, comparative studies such as Lee’s might be useful, Elardo said. “Can you add a fungus…that increases nutrient uptake?” he pondered. “That’s an awesome idea.”

—Alka Tripathy-Lang (@dralkatrip.bsky.social), Science Writer