Source: Global Biogeochemical Cycles

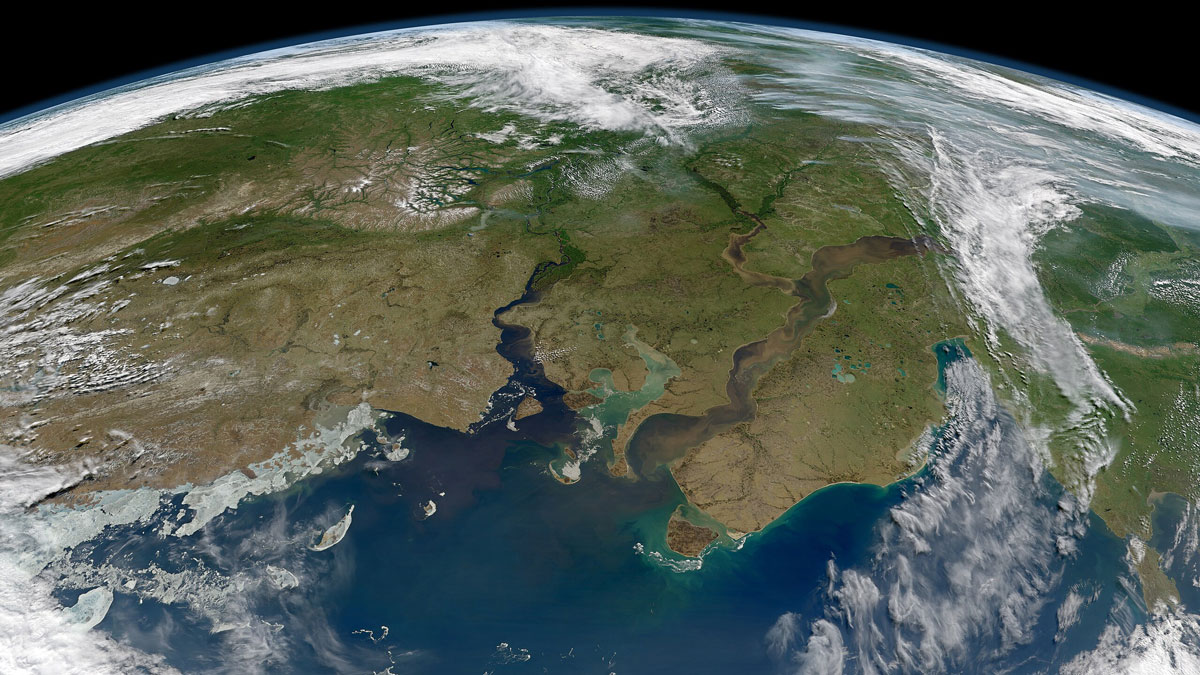

Rivers deliver freshwater, nutrients, and carbon to Earth’s oceans, influencing the chemistry of coastal seawater worldwide. Notably, a river’s alkalinity and the levels of dissolved inorganic carbon it brings to the sea help to shape regional conditions for marine life, including shellfish and corals. These factors also affect the ability of coastal seawater to absorb carbon dioxide from Earth’s atmosphere—which can have major implications for climate change.

However, the factors influencing river chemistry are complex. Consequently, models for predicting worldwide carbon dynamics typically simplify or only partially account for key effects of river chemistry on coastal seawater. That could now change with new river chemistry insights from Da et al. By more realistically accounting for river inputs, the researchers demonstrate significant corrections to overestimation of the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by the coastal ocean.

The researchers used real-world data on rivers around the world to analyze how factors such as forest cover, carbonate-containing rock, rainfall, permafrost, and glaciers in a watershed influence river chemistry. In particular, they examined how these factors affect a river’s levels of dissolved inorganic carbon as well as its total alkalinity—the ability of the water to resist changes in pH.

The researchers found that variations in total alkalinity between the different rivers were primarily caused by differences in watershed forest cover, carbonate rock coverage, and annual rainfall patterns. Between-river variations in the ratio of dissolved inorganic carbon to total alkalinity were significantly shaped by carbonate rock coverage and the amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide taken up by photosynthesizing plants in the watershed, they found.

The analysis enabled the researchers to develop new statistical models for using watershed features to realistically estimate dissolved inorganic carbon and total alkalinity levels at the mouths of rivers, where they flow into the ocean.

When incorporated into a global ocean model, the improved river chemistry estimates significantly reduced the overestimation of carbon dioxide taken up by coastal seawater. In other words, compared with prior ocean modeling results, the new results were more in line with real-world, data-based calculations of carbon dioxide absorption.

This study demonstrates the importance of accurately accounting for river chemistry when making model-based predictions of carbon cycling and climate change. More research is needed to further refine river chemistry estimates to enable even more accurate coastal ocean modeling. (Global Biogeochemical Cycles, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GB008528, 2025)

—Sarah Stanley, Science Writer