A translation of this article was made possible by a partnership with Planeteando. Una traducción de este artículo fue posible gracias a una asociación con Planeteando.

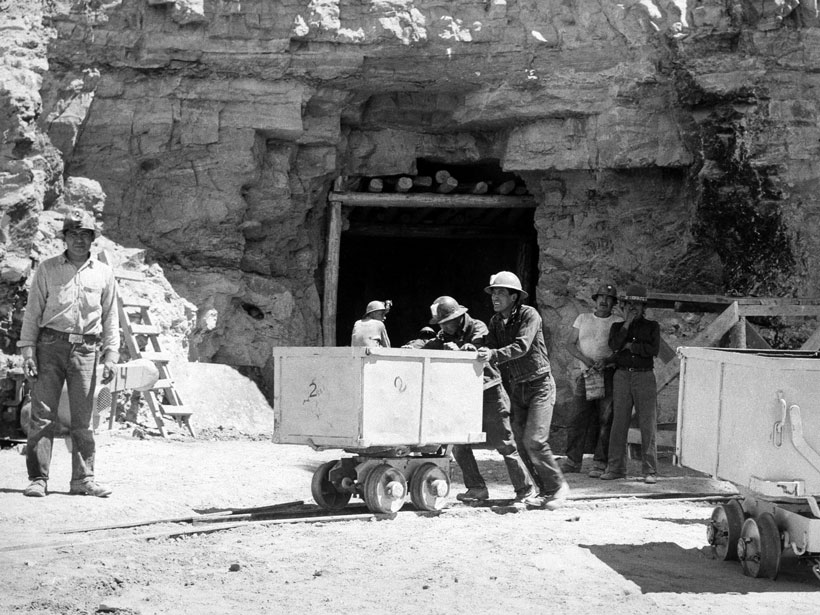

After World War II, the U.S. government announced it would purchase all uranium ore mined in the United States. This announcement fueled a mining boom throughout the country, particularly in the Southwest.

As uranium production soared on and near Navajo lands, many Navajo people worked in the mines with no knowledge of the adverse effects of uranium exposure, even though the association with lung cancer was known at the time. “They thought it was ordinary digging,” said Esther Yazzie-Lewis, coeditor of The Navajo People and Uranium Mining. “[The miner’s] wives would do laundry…their clothes got exposed to uranium.”

Despite passage of the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which acknowledged this historical neglect, risks of contamination at many abandoned mines have still not been properly addressed. For instance, according to Yazzie-Lewis, materials like wood from abandoned mines have been used to build houses, making cleanup a formidable project. Kidney failure and cancer, conditions associated with uranium contamination, continue to affect Navajo people. Filing for compensation can also prove arduous. For people married in traditional Navajo ceremonies, for example, reparative payments can often be difficult to obtain because of the difficulty of proving marital status.

Five federal agencies have been tasked with cleanup at the mines, but the process is slow and riddled with setbacks. In early June 2020, President Trump signed an executive order rolling back environmental reviews. The same month, a federal court ruled against the Havasupai Tribe and environmental groups by allowing a uranium mine to operate near the Grand Canyon.

Thinking Zinc

Despite environmental rollbacks, the scientific community is responding aggressively to the health crisis posed by uranium mining. An ongoing clinical trial at the University of New Mexico called Thinking Zinc seeks to test whether dietary zinc supplements could mitigate the adverse health effects caused by metal exposure. According to Johnnye Lewis, a professor at the Community Environmental Health Program at the University of New Mexico, long-standing relationships with colleagues from the Navajo Nation made the trial possible.

“It is exciting to see [that] what our team learns in the laboratory can actually have meaning for communities by helping to reduce risk,” said Lewis. “There has to be two-way participation.”

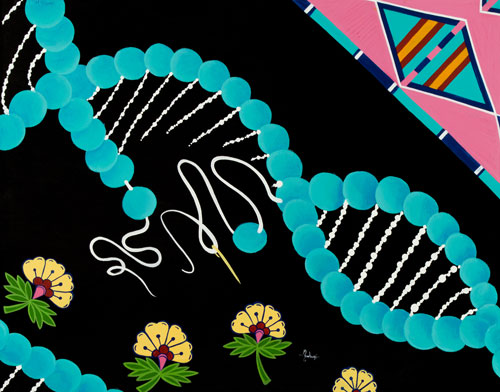

Scientific findings and terminology can be inaccessible to many of the people who would be most affected by the study. Mallery Quetawki, artist-in-residence at the University of New Mexico College of Pharmacy, serves as a cultural liaison on the project to translate findings in a culturally relatable way. Emphasizing the importance of dialogue and cultural sensitivity, Quetawki said it would be a mistake to simply regurgitate data results to the community and expect comprehensive progress to follow. Research is a vital, but insufficient, step in delivering justice to Indigenous communities, she said.

By using a strand of turquoise beads to represent proteins and visually demonstrating how such proteins deteriorate when coming into contact with foreign metals such as uranium, Quetawki frames scientific findings in the lens of Indigenous ways of knowing. “This has allowed people to start dialogues and ask more questions,” Quetawki said, describing her artwork as a “bidirectional communication tool for the community and for the researchers.”

Quetawki’s methodology indicates the paramount importance of trust building and cooperation throughout the research process. This process has the potential, she says, to achieve long-lasting impacts much more than a top-down experiment ever could.

“We need to stop looking at community members as subject matter,” said Quetawki.

Moving Forward

The COVID-19 crisis has introduced new ways for Thinking Zinc researchers to evaluate the effect of uranium mining on public health. According to Lewis, COVID-19 has a huge impact on the production of a class of proteins called cytokines, as does exposure to metals like uranium. To researchers, this relationship indicates the need to evaluate the interaction between the disease and metal exposure.

The pandemic has disproportionately harmed Navajo communities, Lewis notes, and this research will now provide vital scientific insights on how to improve public health outcomes on multiple fronts.

—Ria Mazumdar (@riamaz), Science Writer

Citation:

Mazumdar, R. (2020), Thinking zinc: Mitigating uranium exposure on Navajo land, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO147582. Published on 29 July 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.