From farming and engineering to emergency management and insurance, many industries critical to daily life rely on Earth system and related socioeconomic datasets. NOAA has linked its data, information, and services to trillions of dollars in economic activity each year, and roughly three quarters of U.S. Fortune 100 companies use NASA Earth data, according to the space agency.

Such data are collected in droves every day by an array of satellites, aircraft, and surface and subsurface instruments. But for many applications, not just any data will do.

Leaving reference quality datasets (RQDs) to languish, or losing them altogether, would represent a dramatic shift in the country’s approach to managing environmental risk.

Trusted, long-standing datasets known as reference quality datasets (RQDs) form the foundation of hazard prediction and planning and are used in designing safety standards, planning agricultural operations, and performing insurance and financial risk assessments, among many other applications. They are also used to validate weather and climate models, calibrate data from other observations that are of less than reference quality, and ground-truth hazard projections. Without RQDs, risk assessments grow more uncertain, emergency planning and design standards can falter, and potential harm to people, property, and economies becomes harder to avoid.

Yet some well-established, federally supported RQDs in the United States are now slated to be, or already have been, decommissioned, or they are no longer being updated or maintained because of cuts to funding and expert staff. Leaving these datasets to languish, or losing them altogether, would represent a dramatic—and potentially very costly—shift in the country’s approach to managing environmental risk.

What Is an RQD?

No single definition exists for what makes a dataset an RQD, although they share common characteristics, including that they are widely used within their respective user communities as records of important environmental variables and indicators. RQDs are best collected using observing systems designed to produce highly accurate, stable, and long-term records, although only a few long-term observing systems can achieve these goals.

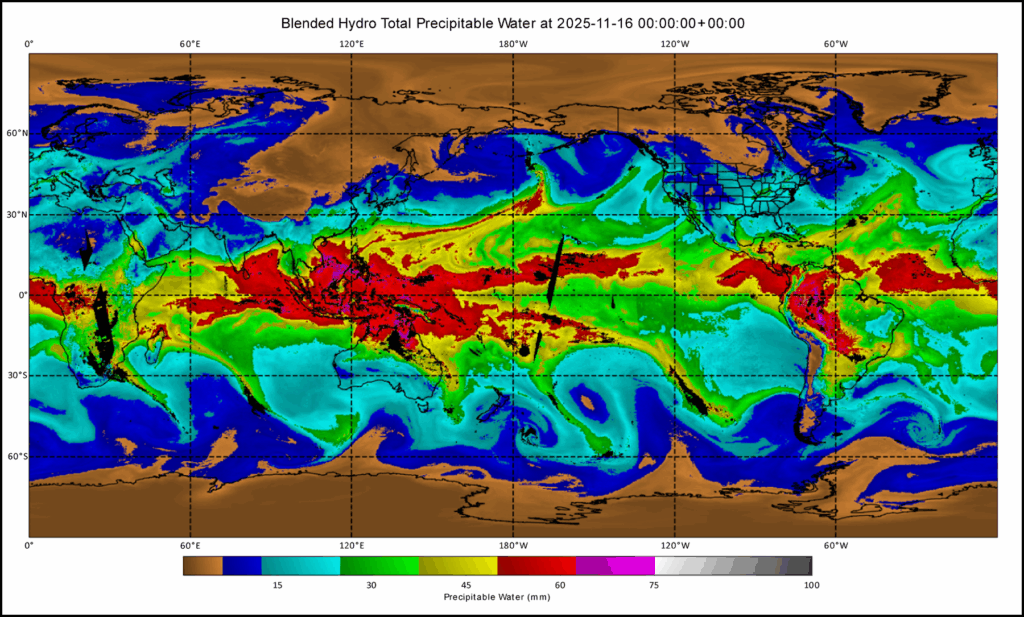

As technological advances and operating constraints are introduced, specialized efforts are needed to integrate new and past observations from multiple observing systems seamlessly. This integration requires minimizing biases in new observations and ensuring that these observations have the broad spatial and temporal coverage required of RQDs (Figure 1). The nature of these efforts varies by the user community, which sets standards so that the datasets meet the specific needs of end users.

The weather and climate community—which includes U.S.- and internationally based organizations such as NOAA, NASA, the National Research Council, and the cosponsors of the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS)—has agreed upon principles to guide the development of RQDs [Bojinski et al., 2014; National Research Council, 1999]. For example, data must account for changes in observing times, frequency of observations, instruments, calibration, and undesirable local effects (e.g., obstructions affecting the instruments’ sensors). These RQDs are referred to as either thematic or fundamental climate data records depending on the postprocessing involved (e.g., sensor-detected satellite radiances (fundamental) versus a postprocessing data product such as integrated atmospheric water vapor (thematic)).

Another important attribute of RQDs is that their data are curated to include detailed provenance tracking, metadata, and information on validation, standardization, version control, archiving, and accessibility. The result of all this careful collection, community input, and curation is data that have been rigorously evaluated for scientific integrity, temporal and spatial consistency, and long-term availability.

An Anchor to Real-World Conditions

RQDs are crucial in many ways across sectors. They are vital, for example, in realistically calibrating and validating projections and predictions of environmental hazards by weather, climate, and Earth system models. They can also validate parameterizations used to represent physical processes in models and ground global reanalysis and gridded model products in true ambient conditions [Thorne and Vose, 2010].

RQDs have become even more important with the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence weather forecasting approaches.

Without these reference data to anchor them, the outputs of large-scale high-resolution gridded climate datasets (e.g., PRISM (Portable Remote Imaging Spectrometer), E-OBS, IMERG (Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM), CHELSA-W5E5) can drift systematically. Over multidecadal horizons, this drift degrades our ability to separate genuine Earth system changes and variations from artifacts. RQDs have become even more important with the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) weather forecasting approaches, which must be trained on observations and model outputs and thus can inherit their spatial and temporal biases.

Indeed, RQDs are fundamental to correcting biases and minimizing the propagation of uncertainties in high-resolution models, both conventional and AI. Researchers consistently find that the choice and quality of reference datasets are critical in evaluating, bias-correcting, and interpreting climate and weather model outputs [Gampe et al., 2019; Gibson et al., 2019; Jahn et al., 2025; Gómez-Navarro et al., 2012; Tarek et al., 2021]. If the reference data used are of lower quality, greater uncertainty can be introduced into projections of precipitation and temperature, for example, especially with respect to extreme conditions and downstream impacts such as streamflows or disease risk. This potential underscores the importance of RQDs for climate and weather modeling.

Each community has its own requirements for RQDs. To develop and implement statistical risk models to assess local vulnerability to environmental hazards, the finance and insurance sectors prioritize high spatial and temporal resolution, data completeness, adequate metadata to dissect specific events, certification that data are from a trusted source, open-source accessibility, and effective user data formats. These sectors directly or indirectly (i.e., downstream datasets) rely on many federally supported datasets. Examples include NOAA’s Storm Events Database, Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters dataset, and Global Historical Climatology Network hourly dataset; NASA’s family of sea surface altimetry RQDs and its Soil Moisture Active Passive and Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment terrestrial water storage datasets; and the interagency Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity dataset, which tracks burned wildfire areas.

Meanwhile, the engineering design community requires regularly updated reference data that can help distinguish truly extreme from implausible outlier conditions. This community uses scores of federally supported RQDs to establish safety and design standards, including NOAA’s Atlas 14 and Atlas 15 precipitation frequency datasets, U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program dataset, and NASA’s sea level data and tools (which are instrumental in applications related to ocean transport and ocean structures).

As RQDs are a cornerstone for assessing environmental hazards across virtually all sectors of society, the loss or degradation of RQDs is an Achilles heel for reliably predicting and projecting all manner of environmental hazard.

Linking Reference Observing and Data Systems

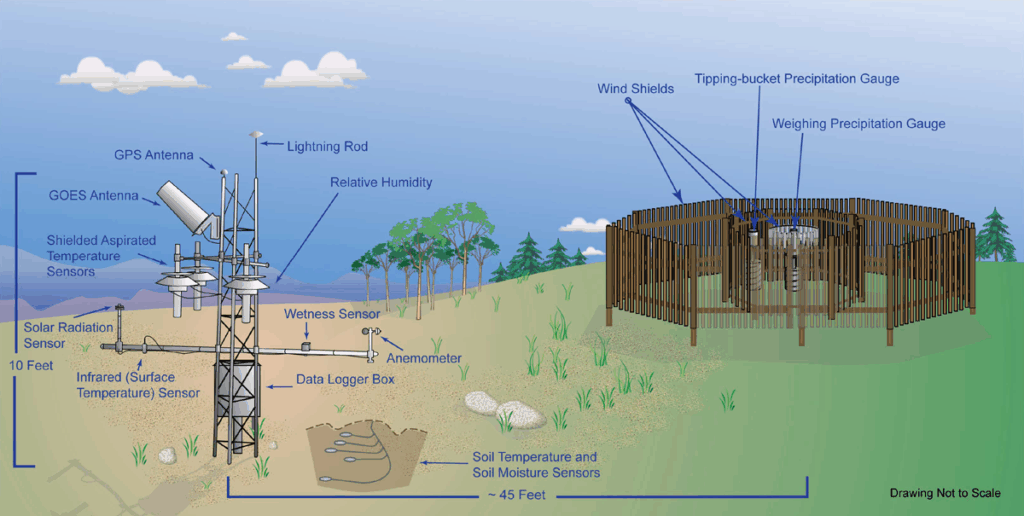

U.S. agencies have long recognized the importance of reference observing systems and the RQDs they supply. Since the early 2000s, for example, NOAA’s U.S. Climate Reference Network (USCRN) has operated a network of highly accurate stations (now numbering 137) across the country that measure a variety of meteorological variables and soil conditions (Figure 2) [Diamond et al., 2013]. The USCRN plans redundancy into its system, such as triplicate measurements of the same quantity to detect and correct sensor biases, allowing data users to trust the numbers they see.

The World Meteorological Organization has helped to coordinate similar networks with reference quality standards internationally. One such network is the GCOS Reference Upper-Air Network, which tracks climate variables through the troposphere and stratosphere (and to which NOAA contributes). The resulting RQDs from this network are used to calibrate and bias-correct data from other (e.g., satellite) observing systems.

Only the federal government carries a statutory, sovereign, and enduring mandate to provide universally accessible environmental data as a public good.

In the absence of such reference quality observing systems, RQDs must be derived by expert teams using novel data analyses, special field-observing experiments, statistical methods, and physical models. Recognizing their importance, Thorne et al. [2018] developed frameworks for new reference observing networks. Expert teams have been assembled in the past to develop RQDs from observing systems that are of less than reference quality [Hausfather et al., 2016]. However, these teams require years of sustained work and funding, and only the federal government carries a statutory, sovereign, and enduring mandate to provide universally accessible environmental data as a public good; other sectors contribute valuable but nonmandated and nonsovereign efforts.

Datasets at Risk

Recent abrupt actions to reduce support for RQDs are out of step with the long-standing recognition of these datasets’ value and of the substantial efforts required to develop them.

Federal funding and staffing to maintain RQDs are being cut through reduced budgets, agency reorganizations, and reductions in force. The president’s proposed fiscal year 2026 budget would, for example, cut NOAA’s budget by more than 25% and abolish NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, although the newest appropriations package diminishes cuts to science. The National Science Foundation–supported National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), which archives field experiment datasets and community model outputs, is at risk of being dismantled.

Major cuts have also been proposed to NASA’s Earth Sciences Division, as well as to Earth sciences programs in the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy (DOE), Department of the Interior, and elsewhere. Changes enacted so far have already affected some long-running datasets that are no longer being processed and are increasingly at risk of disappearing entirely.

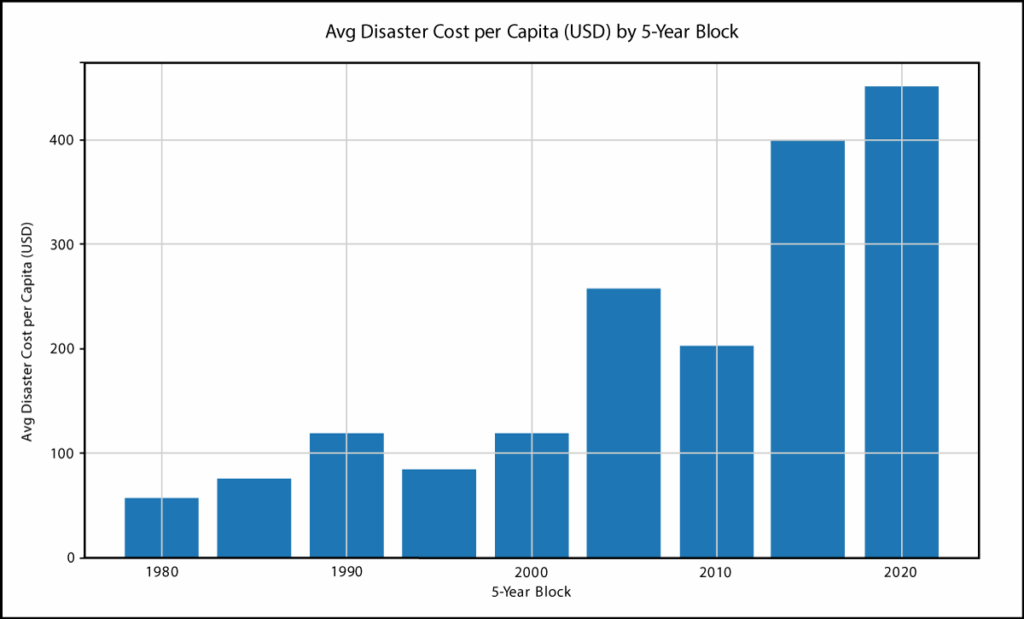

The degradation of RQDs that we’re now seeing comes at a time of growing risk from climate and weather hazards. In the past decade alone, the United States has faced over $1.4 trillion in damages from climate-related disasters—and over $2.9 trillion since 1980. Inflation adjusted per-person costs of U.S. disasters have jumped nearly tenfold since the 1980s and now cost each resident nearly $500 annually (Figure 3). The flooding disasters from Hurricane Helene in September 2024 and in central Texas in July 2025 offer recent reminders of both the risks from environmental hazards and the continued need to predict, project, and prepare for future events.

Threatened datasets include many RQDs whose benefits are compounded because they are used in building other downstream RQDs. This includes examples such as USGS’s National Land Cover Database, which is instrumental to downstream RQDs like Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) crop models, and EPA land use products. Another example is USDA’s National Agriculture Imagery Program, which delivers high-resolution aerial imagery during the growing season and supports floodplain mapping, wetland delineation, and transportation infrastructure planning.

Many other federally supported projects that produce derivative and downstream RQDs are at risk, primarily through reductions in calibration, reprocessing, observing-network density, expert stewardship, and in some cases abrupt termination of observations. Earth system examples include NOAA’s bathymetry and blended coastal relief products (e.g., National Bathymetric Source, BlueTopo, and Coastal Relief Models), USGS’s 3DEP Digital Elevation Model, and the jointly supported EarthScope Consortium geodetic products.

Several global satellite-derived RQDs face end-of-life and longer-term degradation issues, such as those related to NASA’s algorithm development and testing for the Global Precipitation Climatology Project, the National Snow and Ice Data Center’s sea ice concentration and extent data, and the family of MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) RQDs. In addition, USGS’s streamflow records and NOAA’s World Ocean Atlas are at-risk foundational RQDs whose downstream products span sectors including engineering, hazards management, energy, insurance, defense, and ecosystem services.

More Than a Science Issue

The degradation of weather, climate, environmental, and Earth system RQDs propagates risk well beyond the agencies that produce them and isn’t a problem of just science and technology, because the products they power don’t serve just scientists.

Apart from fueling modeling of climate and weather risks and opportunities, they underpin earthquake and landslide vulnerability maps, energy grid management, safe infrastructure design, compound risk mitigation and adaptation strategies, and many other applications that governments, public utilities, and various industries use to assess hazards and serve public safety.

A sustained capability to produce high-resolution, decision-ready hazard predictions and projections relies on a chain of dependencies that begins with RQDs.

A sustained capability to produce high-resolution, decision-ready hazard predictions and projections relies on a chain of dependencies that begins with RQDs. If high-quality reference data vanish or aren’t updated, every subsequent link in that chain is adversely affected, and all these products become harder to calibrate and the information they provide is less certain.

RQDs are often used in ways that are not immediately transparent. A case in point is the critical step of updating weather model reanalyses (e.g., ERA5 (ECMWF Reanalysis v5) or MERRA-2 (Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2)), which are increasingly used in many weather and climate hazards products, by replacing the real-time operational data they assimilate with data from up-to-date RQDs wherever possible. These real-time operational data are rarely screened effectively for absolute calibration errors and subtle but important systemic biases, so this step helps to ensure the model simulations are free of time- and space-dependent biases. Using outputs from reanalysis models not validated or powered by RQDs can thus be problematic because biases can propagate into other hazard predictions, projections, and assessments, resulting in increased uncertainty and an inability to validate extremes.

A Vital Investment

With rapid advances in new observing system technologies and a diverse and ever–changing mix of observing methods, demand is growing for scientific expertise to blend old and new data seamlessly. The needed expertise involves specialized knowledge of how to process the data, integrate new observing system technologies, and more.

The costs for maintaining and updating RQDs are far less than recovering from a single billion-dollar disaster.

Creating RQDs isn’t easy, and sustained support is necessary. This support isn’t just a scientific priority—it’s also a vital national investment. Whereas the costs of restoring lost or hibernated datasets and rebuilding expert teams—if those tasks would even be possible—would be enormous, the costs for maintaining and updating RQDs are far less than recovering from a single billion-dollar disaster.

Heeding recurring recommendations to continue collecting precise and uninterrupted observations of the global climate system—as well as to continue research, development, and updates necessary to produce RQDs—in federal budgets for fiscal year 2026 and beyond thus seems the most sensible approach. If this doesn’t happen, then the United States will need to transition to relying on the interest, capacities, and capabilities of various other organizations both domestic and international to sustain the research, development, and operations required to produce RQDs and make them available.

Given the vast extent of observing system infrastructures, the expertise required to produce RQDs from numerous observing systems, and the long-term stability needed to sustain them, such a transition could be extremely challenging and largely inadequate for many users. Thus, by abandoning federally supported RQDs, we risk being penny-wise and climate foolish.

References

Bojinski, S., et al. (2014), The concept of essential climate variables in support of climate research, applications, and policy, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 95(9), 1,431–1,443, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00047.1.

Diamond, H. J., et al. (2013), U.S. Climate Reference Network after one decade of operations: Status and assessment, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 94(4), 485–498, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00170.1.

Gampe, D., J. Schmid, and R. Ludwig (2019), Impact of reference dataset selection on RCM evaluation, bias correction, and resulting climate change signals of precipitation, J. Hydrometeorol., 20(9), 1,813–1,828, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-18-0108.1.

Gibson, P. B., et al. (2019), Climate model evaluation in the presence of observational uncertainty: Precipitation indices over the contiguous United States, J. Hydrometeorol., 20(7), 1,339–1,357, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-18-0230.1.

Gómez-Navarro, J. J., et al. (2012), What is the role of the observational dataset in the evaluation and scoring of climate models?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39(24), L24701, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL054206.

Hausfather, Z., et al. (2016), Evaluating the impact of U.S. Historical Climatology Network homogenization using the U.S. Climate Reference Network, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43(4), 1,695–1,701, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL067640.

Jahn, M., et al. (2025), Evaluating the role of observational uncertainty in climate impact assessments: Temperature-driven yellow fever risk in South America, PLOS Clim., 4(1), e0000601, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000601.

National Research Council (1999), Adequacy of Climate Observing Systems, 66 pp., Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, D.C., https://doi.org/10.17226/6424.

Tarek, M., F. Brissette, and R. Arsenault (2021), Uncertainty of gridded precipitation and temperature reference datasets in climate change impact studies, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25(6), 3,331–3,350, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-3331-2021.

Thorne, P. W., and R. S. Vose (2010), Reanalyses suitable for characterizing long-term trends, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 91(3), 353–362, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009BAMS2858.1.

Thorne, P. W., et al. (2018), Towards a global land surface climate fiducial reference measurements network, Int. J. Climatol., 38(6), 2,760–2,774, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5458.

Author Information

Thomas R. Karl ([email protected]), Climate and Weather LLC, Mills River, N.C.; Stephen C. Diggs, University of California Office of the President, Oakland; Franklin Nutter, Reinsurance Association of America, Washington, D.C.; Kevin Reed, New York Climate Exchange, New York; also at Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, N.Y.; and Terence Thompson, S&P Global, New York