The public has long been educated to respond to the threat of a tsunami by moving away from the coast and to higher ground. This messaging has created the impression that tsunami impacts are always potentially significant and has conditioned many in the public toward strong emotional responses at the mere mention of the word “tsunami.”

Indeed, in more general usage, “tsunami” is often used to indicate the arrival or occurrence of something in overwhelming quantities, such as in the seeming “tsunami of data” available in the digital age.

The prevailing messaging of tsunami risk communications is underscored by roadside signs in vulnerable areas, such as along the U.S. West Coast, that point out tsunami hazard zones or direct people to evacuation routes. The ubiquity and straightforward message of these signs, which typically depict large breaking waves (sometimes looming over human figures), reinforce the notion that tsunamis pose life-threatening hazards and that people should evacuate the area.

The disparity between the scientific definition of tsunamis and their common portrayal in risk communications and general usage creates room for confusion in public understanding.

Of course, sometimes they do present major risks—but not always.

The current scientific definition of a tsunami sets no size limit. According to the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) [2019], a tsunami is “a series of travelling waves of extremely long length and period, usually generated by disturbances associated with earthquakes occurring below or near the ocean floor.” After pointing out that volcanic eruptions, submarine landslides, coastal rockfalls, and even meteorite impacts can also produce tsunamis, the definition continues: “These waves may reach enormous dimensions and travel across entire ocean basins with little loss of energy.”

The use of “may” indicates that a tsunami, or long wave, by this definition need not be large or especially impactful. If the initiating disturbance is small, the amplitude of the generated long wave will also be small.

The disparity between the scientific definition of tsunamis and their common portrayal in risk communications and general usage creates room for additional confusion in public understanding and potentially wasted effort and resources in community responses. We thus propose revising the definition of tsunami to include an amplitude threshold to help clarify when and where incoming waves pose enough of a hazard for the public to take action.

A Parting of the Waves

Tsunami wave amplitudes can vary substantially not only from one event to another but also within a single event. Following the magnitude 8.8 earthquake off the Kamchatka Peninsula in July, for example, tsunami waves upward of 4 meters hit nearby parts of the Russian coast, whereas amplitudes were much lower at distant sites across the Pacific.

Meanwhile, other disturbances create waves that although technically tsunamis, simply tend to be smaller. Prevailing public messaging about tsunami threats can complicate communications about such smaller waves, including those from meteotsunamis, for example.

Meteotsunamis are long waves generated in a body of water by a sudden atmospheric disturbance, usually a rapid change in barometric pressure [e.g., Rabinovich, 2020]. They are often reported after the fact as coastal inundation events for which no other obvious explanation can be found.

Once a meteotsunami is formed, the factors that govern its propagation, amplitude, and impact are the same as for other tsunamis. However, meteotsunami wave amplitudes are typically smaller than those of long waves generated by large seismic events.

Updating the scientific definition of a tsunami to include a low-end amplitude threshold could help avoid scenarios where oceanic long waves may be coming but evacuation is not required.

As coastal inundations are amplified by sea level rise and thus are becoming more frequent, a greater need to communicate about all coastal inundation events, including from meteotsunamis, is emerging. And with recent progress in understanding meteotsunamis, it is becoming feasible to develop operational warning systems for them (although to date, only a few countries—Korea being one [Kim et al., 2022]—have such systems).

Still, many meteotsunamis do not require coastal evacuations. Given the public’s understanding of the word “tsunami,” however, an announcement that a meteotsunami is on the way could cause an unnecessary response.

Updating the scientific definition of a tsunami to include a low-end amplitude threshold could help avoid such scenarios where oceanic long waves may be coming but evacuation is not required. We suggest that a long wave below that threshold amplitude should be referred to simply as an oceanic long wave or another suitable alternative, such as a displacement wave. Many meteotsunamis, as well as some long waves generated by low-magnitude seismicity and other drivers, would thus not be classified as tsunamis.

Conceptually, our proposal aligns somewhat with various tsunami magnitude scales developed to link wave heights or energies with potential impacts on land [e.g., Abe, 1979]. These scales have yet to be widely accepted by either the scientific community or operational warning centers, however, perhaps because it is difficult to assign a single value to represent the impact of a tsunami. In addition, tsunami magnitude calculations often require postevent analyses, which are too slow for use in early warnings.

We are not proposing yet another tsunami magnitude scale; rather, our idea focuses predominantly on terminology and solely on relatively low amplitude long waves.

Lessons from Meteorology

This kind of threshold classification for naming natural hazards has precedent in other scientific disciplines.

In meteorology, for example, a tropical low-pressure system is designated as a named tropical storm only if its maximum sustained wind speed is more than 63 kilometers per hour. Below that threshold, a system is called a tropical depression. A higher wind speed threshold is similarly specified before more emotive terms such as “hurricane,” “typhoon,” and “tropical cyclone” (depending on the region) are used.

Considering the effectiveness of using thresholds for tropical storm terminology, we anticipate that adopting a formal tsunami threshold could have similar benefits.

Current wind-based tropical storm naming systems have limitations, such as their focus on wind hazards over those from rainfall or storm surge [e.g., Paxton et al., 2024]. However, on the whole, using intensity thresholds for various terms has enhanced the communication of the risks of these weather systems—whether limited or life-threatening—to the public. The straightforward framework helps inform decisionmaking, allowing people in potentially affected areas to determine whether they should evacuate or take other protective measures against an approaching weather system [e.g., Lazo et al., 2010; Cass et al., 2023]. Lazo et al. [2010], for example, underscored that categorizing hurricanes is a powerful tool for easily conveying storm severity to the public, enabling faster and more confident protective action decisions.

Research into tsunami risk communication, including about best practices and regional differences, is limited compared with that related to other hazards [Rafliana et al., 2022]. However, considering the effectiveness of using thresholds for tropical storm terminology, we anticipate that adopting a formal tsunami threshold could have similar benefits for the communication of risk to the public. For example, it could inform decisions about where and when to issue evacuation orders and, equally important, when those orders could be lifted.

Open Questions to Consider

Our proposal raises important questions about the nature of a potential tsunami threshold and how it should be applied.

First, what should the threshold wave amplitude be? There is no obvious answer, and the decision would require careful consideration within the scientific and operational tsunami warning communities, although amplitude threshold–related techniques already used by tsunami warning services may offer useful insights.

For example, the Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Centre (JATWC) issues three categories of tsunami warnings: no threat, marine threat (indicating potentially dangerous waves and strong ocean currents in the marine environment), and land threat (indicating major land inundation of low-lying coastal areas, dangerous waves, and strong ocean currents). JATWC uses an amplitude of 0.4 meter measured at a tide gauge as a minimum for the confirmation of lower-level marine threat warnings [Allen and Greenslade, 2010]. That could be a possible value for our proposed threshold—or at least a starting point for discussion.

An internationally consistent threshold would be ideal, especially considering the expansive reach of tsunamis, but is not necessarily imperative. The terminology for tropical storms is not entirely consistent around the world, yet the benefits for hazard communication are still evident.

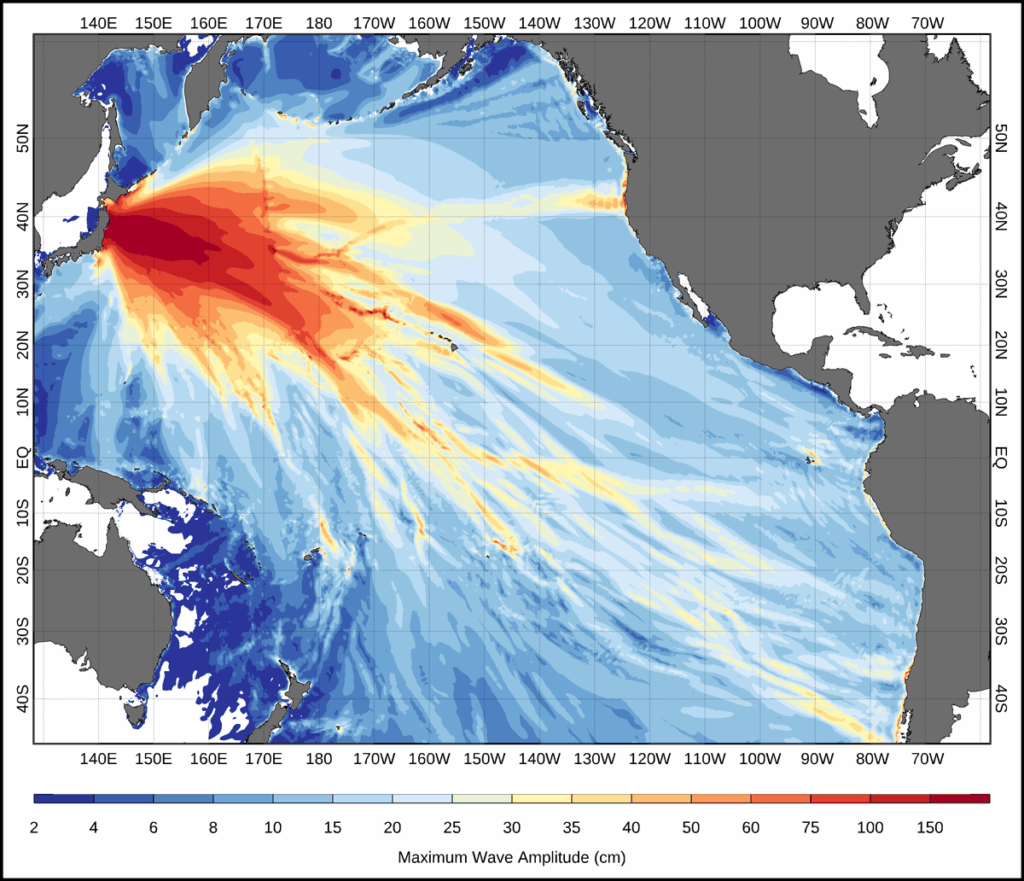

A second question is whether a wave should be considered a tsunami along its entire length once its amplitude anywhere reaches the threshold. We think not and instead propose that long waves be called tsunamis only where their amplitude is above the defined threshold. Were the threshold to be set at 0.4 meter, this provision would mean, for example, that in the hypothetical case following a large earthquake shown in Figure 1, only waves in the orange- and red-shaded regions would be considered tsunami waves.

In this way, the proposed terminology for tsunamis would differ from that used for tropical low-pressure systems, which are classified as storms (or hurricanes, typhoons, etc.) in their entirety once their maximum sustained winds exceed a certain threshold—regardless of where that occurs. While tropical storms typically have localized impacts, long ocean waves can travel vast distances, even globally. However, since the destructive effects of these waves are limited to specific regions—similar to tropical storms—it is reasonable to refer to them as tsunamis only in areas where significant impact is expected.

This location-dependent classification may raise practical challenges for warning centers, in part because details of the forcing disturbance (e.g., the earthquake depth and focal mechanism) may not be immediately available and because of uncertainties about how a long wave will interact with complex coastlines, which can amplify or attenuate waves.

On the other hand, early assessments of where and when an ocean long wave should be defined as a tsunami would benefit from the fact that once a tsunami is generated, its evolution is fairly predictable because of its linear propagation in deep water.

Using amplitude threshold–based definitions will require efforts to educate the public about basic principles and the terminology of ocean waves.

Another issue for consideration is that using amplitude threshold–based definitions will require efforts to educate the public about basic principles (e.g., what wave amplitudes are and why they vary) and the terminology of ocean waves. Ubiquitous mentions of atmospheric pressure “highs” and “lows” in weather forecasts have familiarized the public with terms like “tropical low” and with what conditions to expect when the pressure is low. However, “oceanic long wave” and other such terms are more obscure. Choosing the best term for waves that do not meet the tsunami threshold, as well as the best approaches for informing people, would require social science research and testing with the public.

Finally, how do we ensure that this tsunami threshold terminology prompts appropriate public reactions, whether that is evacuating coastal areas entirely, pursuing a limited response such as securing boats properly and staying out of the water, or taking no action at all? Scientists, social scientists, and the emergency management and civil protection communities must collaborate to address this question and to test the messaging with the public. Using official tsunami warning services to issue warnings about above-threshold events and more routine marine and coastal services, such as forecasts of sea and swell in coastal waters, to share news about below-threshold events might be an effective way to help the public understand the potential severity of different events and react accordingly.

Normalizing and Formalizing

Should the use of a tsunami amplitude threshold be adopted for risk communications, we advocate that ocean scientists should also adhere to the terminology in presentations and research publications in the same way that atmospheric scientists have adhered to the threshold-dependent terminology around tropical storms. This consistency will gradually normalize the usage and reduce confusion. Readers of a scientific publication that notes the occurrence of a tsunami, for example, would instantly know that it was an above-threshold event.

Formalizing a scientific redefinition of what constitutes a tsunami will require discussion, agreement, and coordination across multiple bodies, most notably the IOC, which supports the agencies that provide tsunami warnings, and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which supports the agencies that provide marine forecasts. Should this threshold proposal receive enough initial support, the next step would be to elevate the proposal to the IOC and WMO for further consideration in these forums.

Considering the potential benefits for risk communications and the well-being of coastal communities worldwide, we think these are discussions worth having.

References

Abe, K. (1979), Size of great earthquakes of 1837–1974 inferred from tsunami data, J. Geophys. Res., 84, 1,561–1,568, https://doi.org/10.1029/JB084iB04p01561.

Allen, S. C. R., and D. J. M. Greenslade (2010), Model-based tsunami warnings derived from observed impacts, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 10, 2,631–2,642, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-10-2631-2010.

Cass, E., et al. (2023), Identifying trends in interpretation and responses to hurricane and climate change communication tools, Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., 93, 103752, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103752.

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (2019), Tsunami Glossary, 4th ed., IOC Tech. Ser. 85, U.N. Educ., Sci. and Cultural Organ., Paris, unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000188226.

Kim, M.-S., et al. (2022), Towards observation- and atmospheric model-based early warning systems for meteotsunami mitigation: A case study of Korea, Weather Clim. Extremes, 37, 100463, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2022.100463.

Lazo, J. K., et al. (2010), Household evacuation decision making and the benefits of improved hurricane forecasting: Developing a framework for assessment, Weather Forecast., 25(1), 207–219, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009WAF2222310.1.

Paxton, L. D., J. Collins, and L. Myers (2024), Reconsidering the Saffir-Simpson scale: A Qualitative investigation of public understanding and alternative frameworks, in Advances in Hurricane Risk in a Changing Climate, Hurricane Risk, vol. 3, edited by J. Collins et al., pp. 241–279, Springer, Cham, Switzerland, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63186-3_10.

Rabinovich, A. B. (2020), Twenty-seven years of progress in the science of meteorological tsunamis following the 1992 Daytona Beach event, Pure Appl. Geophys., 177, 1,193–1,230, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02349-3.

Rafliana, I., et al. (2022), Tsunami risk communication and management: Contemporary gaps and challenges, Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., 70, 102771, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102771.

Author Information

Diana J. M. Greenslade ([email protected]) and Matthew C. Wheeler, Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Vic., Australia