Research & Developments is a blog for brief updates that provide context for the flurry of news that impacts science and scientists today.

Rising sea levels have put thousands of facilities containing hazardous materials at risk of flooding this century, according to a new study published in Nature Communications.

Global sea level rise is accelerating, leading to an increase in coastal flooding that scientists expect to worsen. As seas rise, floodwater reaches infrastructure that was not built to withstand it.

“Flooding from sea level rise is dangerous on its own—but when facilities with hazardous materials are in the path of those floodwaters, the danger multiplies.”

These extreme events can release toxins into the environment. For example, an estimated 10 million pounds of pollutants from refineries, petrochemical facilities, and manufacturing sites spilled into the environment following flooding from Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

The new study reports that 5,500 facilities containing hazardous substances are at risk of a similar event, threatening the health of nearby communities.

“Flooding from sea level rise is dangerous on its own—but when facilities with hazardous materials are in the path of those floodwaters, the danger multiplies,” Lara Cushing, an environmental researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles and lead author of the new study, told The Guardian.

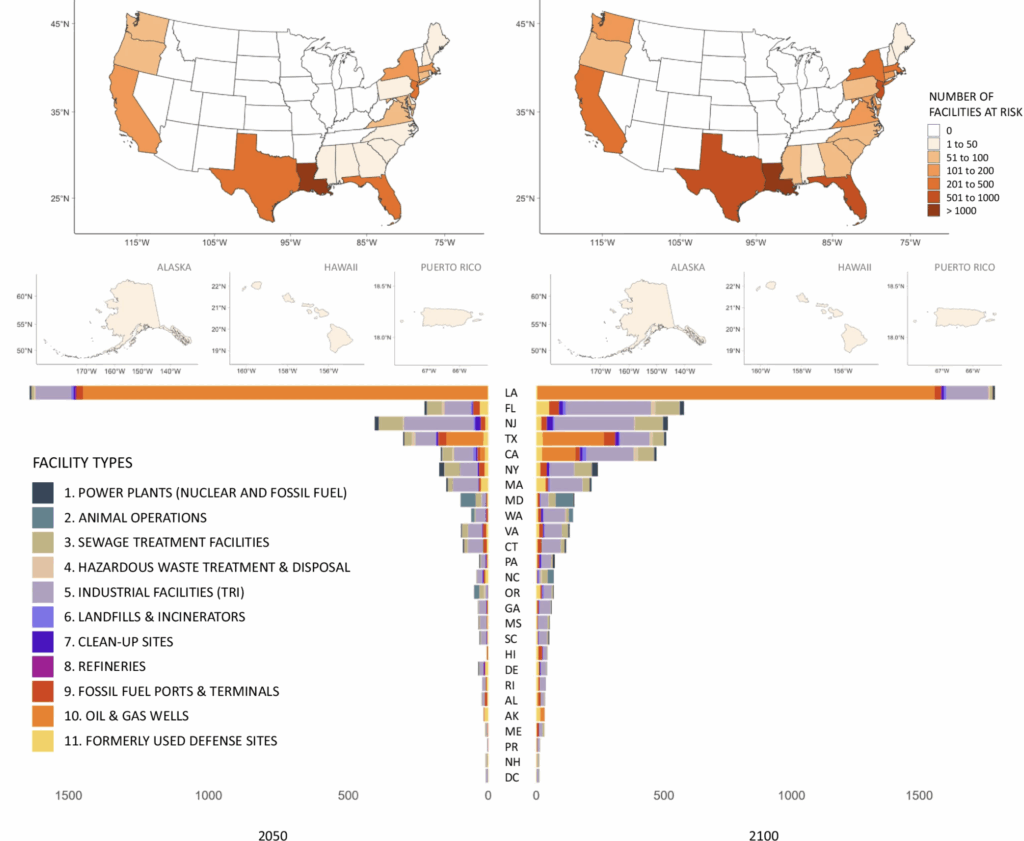

In the study, scientists analyzed the location of 47,646 coastal power plants, sewage treatment facilities, fossil fuel infrastructure sites, industrial facilities, and former defense sites. Then, they used sea level rise projections under various climate scenarios to determine whether those sites were at risk from a 1-in-100-year flood event by 2100.

They found that 11% of the sites analyzed were at risk of such a flood by 2100 in a high-emissions, business-as-usual scenario (RCP 8.5). Eighty percent of the at-risk sites were in just seven states: Louisiana, Florida, New Jersey, Texas, California, New York, and Massachusetts. Oil and gas wells made up a large proportion of sites considered to be at risk.

In total, 22% of coastal sewage treatments facilities, 24% of coastal refineries, 44% of coastal fossil fuel ports and terminals, 12% of coastal industrial facilities, 21% of former coastal defense sites, and 21% of coastal fossil fuel and nuclear power plants are at risk of flooding by 2100.

Disproportionate Effects

Marginalized groups are more likely to live near hazardous waste sites and industrial facilities, making these groups more vulnerable when such facilities flood.

In the study, researchers analyzed the location of at-risk sites compared to community demographics. They found that households in Hispanic neighborhoods, households with incomes below twice the federal poverty line, and households that rented rather than owned their homes were especially likely to be located within one kilometer (0.62 miles) from a facility at risk of flooding.

Related

• Read the study: “Sea level rise and flooding of hazardous sites in marginalized communities across the United States.”

• Climate Central Report: Toxic Tides

• Thousands of Toxic Sites Across U.S. Face Risk of Coastal Flooding

• Sea Level Rise Threatens Hundreds of Wastewater Treatment Plants

• Sea Level Rise May Swamp Many Coastal U.S. Sewage Plants

“These projected dangers are falling disproportionately on poorer communities and communities that have faced discrimination and therefore often lack the resources to prepare for, retreat, or recover from exposure to toxic floodwaters,” Cushing said.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is key to slowing sea level rise and reducing flooding. The study’s projections showed that restricting greenhouse gas emissions to a low-emissions scenario (RCP 4.5) would reduce the number of at-risk sites from 5,500 to 5,138.

In addition, the authors write that keeping communities safe from future hazardous floodwaters will require federal and state governments to “provide publicly available, accessible, and continually updated data on projections of [sea level rise]-related flooding threats.”

—Grace van Deelen (@gvd.bsky.social), Staff Writer

These updates are made possible through information from the scientific community. Do you have a story about science or scientists? Send us a tip at [email protected].