NOAA released this year’s Arctic Report Card on 16 December at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2025 in New Orleans. The report gives an update on changes to the region’s climate, environment, and communities and documents these changes for future scientists looking to the Arctic’s past.

After 2 decades of the U.S. government producing the annual report, however, datasets and resources used to create it may be under threat as federal science agencies lose staff and plan for funding uncertainties.

“There is growing concern over how the U.S. will be investing in Arctic research,” said Matthew Druckenmiller, an Arctic scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center and lead editor of the report.

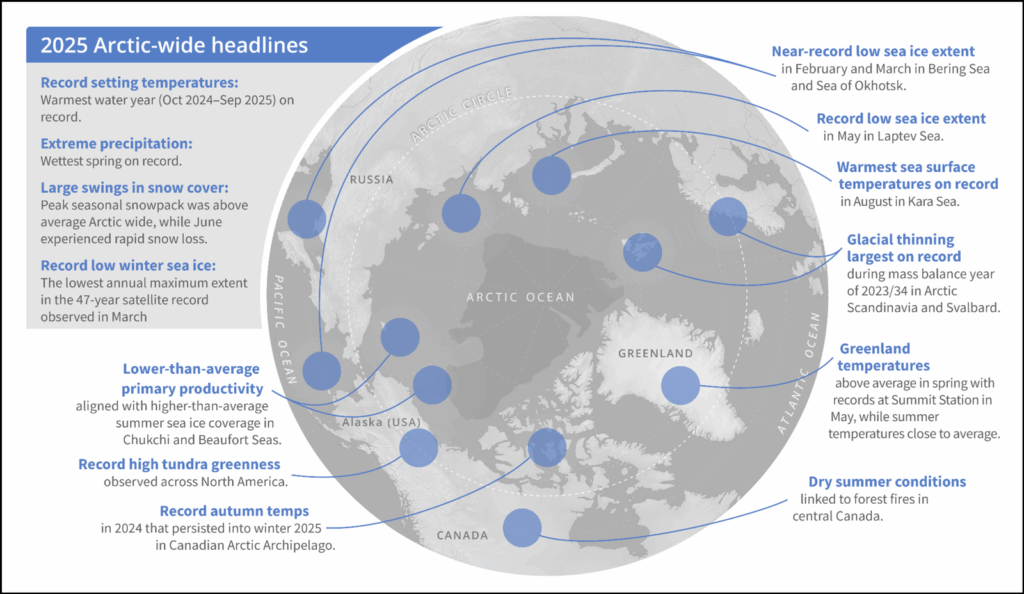

Another Year of Arctic Records

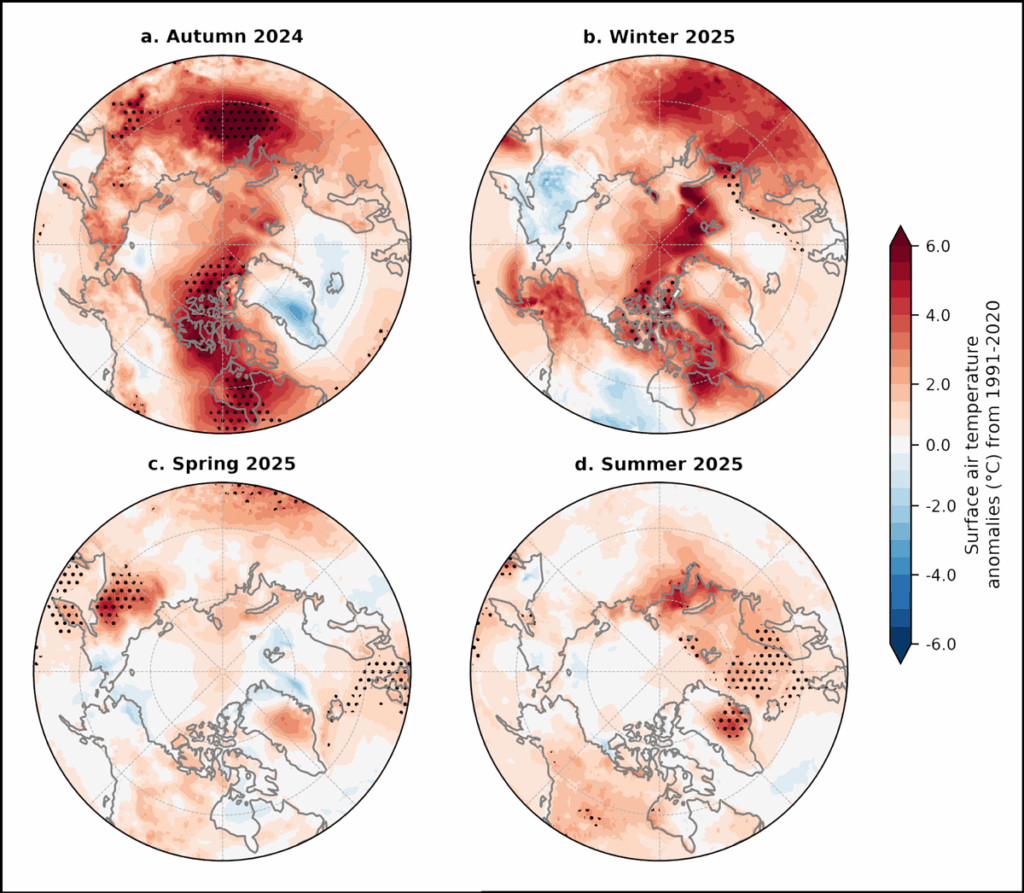

From October 2024 to September 2025, the time period analyzed by the report, Arctic surface air temperatures were the warmest on record. The past year in the Arctic marked the region’s warmest autumn, second-warmest winter, and third-warmest summer ever.

This year, the Arctic also had the most precipitation ever recorded, with its wettest spring on record and higher than normal winter snow cover. “To see both those records [precipitation and surface air temperature] set in a single year was remarkable,” Druckenmiller said.

Sea ice in the Arctic continues to hit new lows: Maximum sea ice extent this winter was the lowest observed in the 47-year satellite record. As sea ice shrinks, the Arctic becomes less reflective, exacerbating climate change as the region absorbs, rather than reflects, more heat from the Sun. Ice on land also continues to melt—the Greenland Ice Sheet lost mass in 2025, as it has every year since the late 1990s.

As the region warms, the Arctic Ocean and associated waterways are changing, too. “Atlantification,” a northward intrusion of warm, salty water from the Atlantic, is altering the Arctic Ocean, leading to decreased winter sea ice and creating conditions for more frequent algal blooms. How this influx of water will affect ecological communities in the Arctic remains one of the biggest unanswered scientific questions about the Arctic, said Igor Polyakov, an oceanographer at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and coauthor of the report.

Data Difficulties

Data included in the report are collected by the Arctic Observing Network (AON), an internationally coordinated system of data observation and sharing.

But obstacles impede the system’s ability to monitor the Arctic, according to report authors. Sparse ground-based observation systems, unreliable infrastructure, limited telecommunications, and satellites operating beyond their mission lifetimes are hindering data collection and sharing. “Persistent gaps limit the AON’s ability to fully support Arctic assessments and decision-making,” the authors write.

Science agencies such as NOAA, NASA, and the National Science Foundation and the Interior Department contribute significantly to AON, but all faced staff and budget reductions in 2025. These changes could affect AON and its ability to publish the Arctic Report Card, “jeopardizing long-term trend analyses and undermining decision-making,” the authors write.

Though the Arctic Report Card team received “great support” from NOAA and the report was successfully published, “there were some difficult moments this year,” Druckenmiller said.

“Data doesn’t interpret itself.”

In particular, the shutdown of climate.gov, the NOAA website that housed most of its climate science information, slowed the team’s ability to create the report’s graphics. The federal shutdown in October and November delayed the processing of key datasets, notably one from NASA that documented surface air temperature.

In addition, the report points out that federal budget proposals for 2026 may affect multiple datasets and observation systems used in the report. The three primary sea ice–observing systems (CryoSat-2, Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS), and Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite 2 (ICESat-2)) are all operating past their mission lifetime, as well. And in July, the Department of Defense decommissioned its Defense Meteorological Satellite Program, which tracked meteorological, oceanographic, and solar-terrestrial physics in the Arctic and elsewhere.

“When these long-standing data products are decommissioned, you really lose a lot of data continuity, which is really important if you’re going to accurately document long-term trends,” Druckenmiller said.

Losing expert scientists at federal science agencies, labs, universities, and research institutions will likely pose challenges, too, he added. “Data doesn’t interpret itself.”

Indigenous-Led Data Collection

Rapid changes to the Arctic are stressing the human communities there: Permafrost thaw releases potential toxicants into drinking water, wetter weather contributes to flooding, and changes to snowfall and ice affect travel. The remnants of Typhoon Halong brought extreme winds and surging water to Alaska’s southwestern coast in October 2025, flooding communities and forcing more than 1,500 residents to evacuate.

Data give these communities—many of which are majority Indigenous—a better ability to respond to climate change, and a weaker AON could impede flood prediction and community adaptation plans, the report states.

As the availability of federal data and resources remains uncertain, Indigenous-led monitoring networks highlighted in the report have provided another model.

The Indigenous Sentinels Network, for example, is a tribally owned and operated cyber infrastructure system supporting Indigenous-led environmental monitoring. Sentinels collect observational data on a range of environmental systems, from wildlife to coastal erosion to tundra greening. The data collected are governed by the communities that collect them and used locally for decisionmaking, collaborative research projects, and climate adaptation planning.

The Building Research Aligned with Indigenous Determination, Equity, and Decision-making (BRAIDED) Food Security Project, another example of an Indigenous-led monitoring project, tracks mercury in locally harvested foods to ensure food safety. All the samples are processed and tested locally on St. Paul Island in Alaska.

“These are models that can be used for resilience everywhere.”

This type of place-based, community-led monitoring is “foundational to understanding and responding to rapid change” facing the Arctic, said Hannah-Marie Ladd, program director for the Indigenous Sentinels Network and author of the new report.

“Indigenous-led monitoring can, and always has, complemented federal science by providing year-round, place-based observations that are often missing” from short-term field seasons, she said. “[Sentinels] live in these environments, and they can detect changes earlier and interpret them with cultural and ecological context that is often missing when outside entities come into a new relationship with a place.”

Such a framework will become only more valuable as the Arctic, and the rest of the world, warms. “These are models that can be used for resilience everywhere,” Ladd said.

—Grace van Deelen (@gvd.bsky.social), Staff Writer